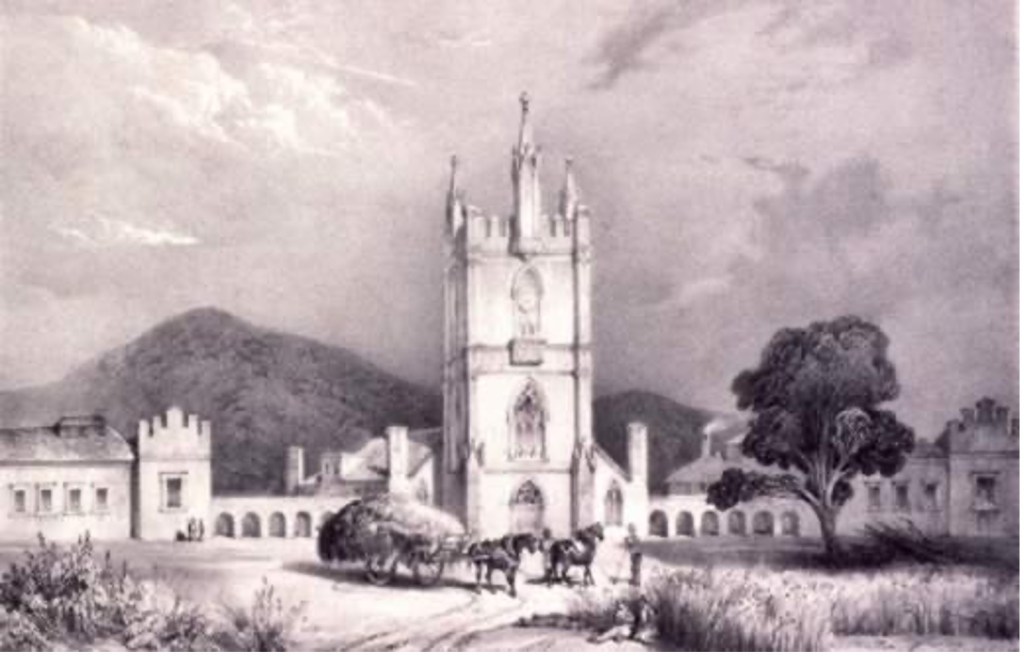

The King’s Orphan Asylum, later known as the Queen’s Orphan Schools, the girls’ school to the left of the chapel, boys’ school to the right, Mount Wellington in the background. The idyllic scene masked the horrors which were imposed on its inmates.

Bruce Lindsay has researched and written about the life and times of his great grandfather, John Lindsay. John was the son of Scots highland Traveller parents, transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) at the age of three with his mother, Mary, in the mid-1830s. Mary had been one of a group of travellers who invaded a home-based store at Sweetie Hillock (just outside Aberdeen), and stole a number of items, including clothing, food and drink. Mary was transported for fourteen years, accompanied by young John. His story throws much light on the little-known life experiences of transports to Australia (whether convicted or not) and is a valuable historical record. Below is an edited version of a chapter from Bruce’s fascinating colonial family history.

*

John Lindsay is thought to have been born at Inverness on 15th January 1832, in the year following the marriage of Isaac Williamson and Mary Lindsay. Common Scots naming practice at the time was for the bride to retain her maiden name, although children generally adopted their father’s surname. However, children of female convicts travelled under their mother’s name, and without this convention, we may have never established the connection to our family line.

John first appears in our records sitting in the tinkers’ horse-drawn cart in March 1835, while his parents and the rest of the troupe confronted the shopkeepers at Sweetie Hillock. After his safe arrival in Hobart with his mother on 25th April 1836, and following a decision by Lt Governor Arthur on 4th May 13 children of mothers confined at the Cascades Female Factory were admitted on 5th May to what was then known as King’s Orphan Asylum (from 1837, upon assumption of the British throne by Queen Victoria, as the Queen’s Orphan Schools). Surviving records show John was listed as “#341, John Linsay (sic), Age 3 at Sept 5 1836, Father unknown, Mother a Prisoner”. Routine practice was to remove children from convict women, either for the term of their mothers’ servitude, or until they reached the age of 14.

The orphanage is described by contemporary and later observers as a severe and uncaring place, in which young John may well have felt intimidated and alone. Robert Hughes, in his seminal work The Fatal Shore, quotes the Reverend Robert Crooke – catechist with the Van Diemen’s Land Convict Department at the time – as saying:

“The slightest offence, whether committed by boy or girl, was punished by unmerciful flogging and some of the officers, more especially females, seem to have taken a delight in inflicting corporal punishment… The female superintendent was in the habit of taking girls, some of them almost young women, to her own bedroom and for trifling offences… stripping them naked, and with a riding whip or a heavy leather strap flagellating them until their bodies were a mass of bruises” (p. 525).

A surviving Report on the state and conduct of the orphan schools dated 30th August, 1848, by the Inspector of Schools, Charles Bradbury, provides depressing details of the physical and educational conditions under which John and the other inmates lived. He said:

“The punishments employed are the cane, solitary confinement, and in extreme cases the birch; few of the latter only have occurred during the last four years. Solitary confinement is inflicted perhaps once in the course of a fortnight; 48 hours have been resorted to as a severe punishment, but the customary time is about two or three hours. The offences, so far as I could ascertain, appear to be those ordinarily incident to large schools; there are none of a flagrant character, petty stealing, violence, and oppression towards each other; occasional indecent and blasphemous language are the chief varieties of misconduct.”

(This report was part of a despatch from Lt. Governor Sir William Denison to Earl Grey and was copied from the British Parliamentary Papers Volume 8, pp356-374, held at the University of Tasmania Library).

In her comprehensive study of children’s lives at the orphanage, Joyce Purtscher (Children in Queen’s Orphanage, Hobart Town, 1828-1863) describes a daily regimen beginning at 5.00am in Summer or 6.00-6.30am in Winter, with a mix of play and classroom instruction. Inspector Bradbury recorded that:

“The industrial training is on a very limited scale: the trades taught are only those of the tailor, shoemaker, and baker. Not one of the boys is employed in farming or gardening. The boys in the shoemaker’s shop are taught repairs alone, not one can cut out, or is acquainted with the making of a shoe. The shoes in the first instance are supplied from the Ordinance Storekeepers’ Department”.

Since internal records from the orphan schools do not survive, if indeed they were ever kept, we cannot confirm whether John may have undertaken basic training in shoemaking during his time there, even though he later practised the trade with his stepfather, William Higgs.

Schooling took place in large single rooms 50’ X 30’, heated by one small fireplace. Bradbury noted that the only teachers in the boys’ school, girls’ school and infants’ school were unqualified and had never previously been engaged as teachers. This was reflected in the children’s typically poor reading and writing skills, of which Bradbury was scathingly critical.

Of the children’s very limited scholastic abilities he observed somewhat laconically:

“I found the members of the upper classes with reference to secular information very deficient, far below the average of the primary schools I am accustomed to visit. Several, especially in the first class, can read with tolerable correctness, though with no expression; but they cannot explain the meanings of many of the commonest words…”, “There is nothing attractive, stimulating, or strengthening in the whole routine, and, at the same time, little actual information is given, that the memory may possibly retain. It would seem, indeed, that, for the ages of the children, their mental capacity and intelligence, are, as a general result, in inverse proportion to the duration of their attendance in the school”.

He further noted that the children’s capacity to learn was not helped by the fact that they were required to stand in class, there being no seating.

Care of the boys’ physical wellbeing was apparently as peremptory as their schooling. They slept in hammocks 80 to a dormitory, and bathed their upper bodies in cell-like rooms paved with flagstones, with stone water troughs in their centre. There was no hot water. Once a week, winter and summer, they were taken to the Derwent River to bathe. Bradbury observed

“In the personal habits of the boys, I think cleanliness and order might to a much greater extent be enforced. In their dress they are mostly untidy, and in some instances so dirty, that it is unpleasant to stand near them, from the odour arising from their outer clothes”.

The orphanage was always overcrowded, hastening the spread of any disease, and in 1843 (while John was there) 56 children died from Scarlet Fever. Even the handsome convict-built stone chapel – St John’s Anglican Church – was heated only by four small fireplaces, one of which was located conveniently abreast of the Governor’s pew. The children could freeze, but not His Excellency.

The interior (2014) of St John’s Anglican Church, New Town, which doubled as the chapel for the Orphan Schools. The gallery shown was used to accommodate the orphans, girls to the left of the monitors’ enclosure, boys to the right. Free settlers rented named and lockable pews on the ground floor (now replaced with standard movable pews facing the sanctuary).

Given several damning assessments of the incompetence of the orphan schools’ provision neither of physical care, nor of any stimulating curriculum or training, it is heartening that young John not only survived the time he spent there, but appears to have emerged ready to take his place in the world. From such unpromising parentage, and such inadequate schooling, he appears to have become a sober, hard-working young man with strong ethics and family values. His later service to his large family was augmented by a willingness to become involved in community affairs (when living at Winslow in Victoria), and the generation by the community of genuine respect and affection for the man.

Originally the Chapel for the orphan schools, this handsome building, designed by Colonial Architect John Lee Archer, and built with convict labour in 1835, is now St John’s Anglican Church, New Town – WITH heating.

Boys’ section of the Queen’s Orphan Schools, where John survived 11 years from 1836 to 1847. Photographed in 2012, and externally largely unchanged, it then housed the “Meals on Wheels” organisation.

Joyce Purtscher further tells us:

“When children turned 14 years of age, they were apprenticed out. They had to work for no money until they were 18. They were at the mercy of their masters regarding food, clothing and housing”.

John was released from the orphanage on 26th August 1847, and apprenticed to Mrs Mary Cox, a remarkable woman who had operated several businesses in Launceston. Her late husband, John Edward Cox, was licensee initially of the Macquarie Hotel in Hobart, and later the Cornwall Hotel in Launceston, owned by John Batman – the co-founder of Melbourne. He also initiated Tasmania’s first coaching service between Launceston and Hobart, and fathered nine children, eight of whom survived. Upon his death in 1837, responsibility for management of family and businesses fell to his wife.

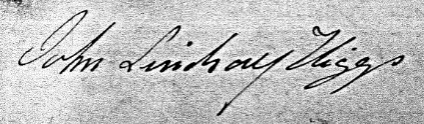

Assuming that, as outlined by Joyce Purtscher above, John was required to work for Mrs Cox without payment until he was 18 years old, by 1851 he would have been free to live and work where he pleased. We know from the 1848 Census that Mary Lindsay and William Higgs were then living together in Adelaide Street, Westbury (after marrying there in 1844), and Higgs had resumed his trade as a shoemaker. John probably joined them after leaving Mrs Cox. Surviving records do not tell us in what trade or capacity John was indentured, but it is possible that he learned the basics of shoemaking when at the Orphan School. Since on the title to his Westbury property later in the 1850s he is listed as a shoemaker, he evidently joined his stepfather in the trade, although this possibility has not been confirmed by searches for business registrations or commercial advertisements. But we know that at that time he adopted his stepfather’s surname, becoming known as John Lindsay Higgs.

John’s signature on the title deed for 1 Reid Street, Westbury, which he sold on 28.5.1862

Under that name he married Charlotte Wells at Westbury on 3rd July 1857. Charlotte was the free-born daughter of former convicts Robert Wells and Margaret Casey. They married in her parents’ private home “according to the Rites and Ceremonies of the Wesleyan Church”. Although born of convict parents on 13th January 1839, Charlotte never suffered the horrors of the Queen’s Orphan School, having been raised by her parents in Longford and Launceston.

John appears to have been industrious and successful in his trade, since he managed to acquire property in Westbury, and ultimately to sustain a large family. It seems that the married couple lived on a block of land in what is now Reid Street, Westbury, purchased on John’s behalf by Higgs, where Charlotte gave birth to their first child – John – on 5th July 1858. In 1859, with Higgs subsiding into alcoholism, John acquired the nine-acre block owned by him on Suburb Road, Westbury, from the mortgagees to whom it had been surrendered. They continued to live at Reid Street, where Charlotte produced their second child – Alexander – on 28th October 1859. Their third child – Robert – was born on 5th May 1861.

John was devastated by his step-father’s suicide on 17th December, 1861. For reasons unknown, he shortly thereafter sold the Reid Street property and acquired a 160-acre rural block at Liffey Plains, near Westbury, from where we presume he continued his shoemaking business. He also deleted “Higgs” from his surname, reverting to “Lindsay”. In the absence of Title records, we must presume he sold the Liffey Plains property late in 1862, then embarked from Launceston with the family aboard the Western for Portland, Victoria, arriving there on 9th August 1862. It is possible that he sought to remove himself from the strong social stigma attaching to suicide at the time, and make a new start with his wife and family.

They settled at Winslow, a small town north of Warrnambool in Victoria’s Western District, where John probably established a shoemaking business in his own name, and from 1883 he and Charlotte assumed management of the local Post Office. Their family continued to grow and Charlotte produced 14 healthy children over a period of 28 years – the last when she was 48 years old – a quite remarkable achievement now, and even more so on the cusp of the 20th century.

The Winslow Post Office and store, attached to the south east front corner of the house in which John, Charlotte and their family resided from 1893 to 1922.

John died on 20th November 1890, when drawing water from a freshwater lake about 100 metres from the back of the family home in Winslow. To reach the water, it was necessary to descend steps, from which newspaper accounts reported John slipped and fell. One of his daughters discovered his hat and coat floating on the surface, and raised the alarm. By the time help arrived, John could not be revived. His age was given as 56 years, though if his assumed birth-date of 1832 is correct, he would have been 58.

The sometime freshwater lake in which John drowned while drawing water for his family. The house is off to the left of this picture, about 100m away. Since that time, a tannery operated on the lake’s shore, and the water is now brackish.

So ended the last direct family connection to the redoubtable Mary Lindsay. The large family produced by John and Charlotte developed in ways that Mary as a Highland Traveller could never have imagined. John’s wife Charlotte lived until 7th January 1922, dying at Winslow from a cerebral haemorrhage and pneumonia, aged 83.

John Lindsay, wife Charlotte and infant daughter, Eliza rest at Tower Hill cemetery near Warrnambool.

*

Readers may also be interested in my book Condemned: The Men, Women and Children Who Built Britain’s Empire, which includes the Van Diemen’s Land experience, though not the King’s Orphanage story. My thanks to Bruce for bringing it to my attention and for allowing this part of his family history research to appear on Gristly History.