Landscape with Swagman (also known as The swagman’s camp by a billabong), painting by Gordon Coutts, oil on canvas, 35.6 x 45.7 cm stretcher; 55.0 x 65.2 x 7.7 cm frame : 0 – Whole; 35 x 45 cm Art Gallery of NSW

Sometimes said to be the world’s most recorded song, the origins of Australia’s accidental anthem, ‘Waltzing Matilda’, has troubled historians and folklorists for a century or so. Just when was it first composed. In what circumstances, where and by whom?

Any number of competing and conflicting theories have been put forward in what seems to be a never-ending flow of books on the subject. Now, W Benjamin Lindner has come up with the most definitive answer to date. Applying the forensic skills of a criminal barrister and a rigorous historical approach to a decidedly ‘two pipe problem’, as Sherlock Holmes might have put it, Lindner’s detective work has convincingly solved the case. It’s all in his Waltzing Matilda: Australia’s Accidental Anthem. A Forensic History (Boolarong Press, 2019).

Not wanting to spoil the story, I won’t give away his conclusion, so you’ll need to check out the book to find the answer. Despite its deep engagement with archival records and the other dry-as-dust stuff that historians like to engage with, it is a good read. While it sets out to prove a particular and important chronological point about the composition of the song, it necessarily tells the human stories of the people most closely involved with it, at the time, and later.

These are, of course, the two main characters, A B ‘Banjo’ Paterson and Christina Macpherson. Paterson thought so little of his dashed-off lyric that he sold the rights to his publisher for five pounds and hardly ever talked about it again. Repurposing a catchy Scots tune, often said to be one of the most recorded songs of all time, Christina Macpherson, mostly got lost in the condescension of posterity. But now she is confirmed in her proper place as the composer of our national song.

And there is a supporting cast of often-colourful other characters who were in on the original events behind the song, as well as later writers who put their efforts towards working out exactly what happened when and where. These include Sydney May, the first person to take an interest, starting seriously in the 1940s. He was misled by some of the accounts he collected but gets the credit for setting the Matilda hunt waltzing.

Then there was the no-nonsense bushman, Richard Magoffin, raised near the legendary site of composition, Dagworth Station. With a commendable disdain for academic historians and the complex copyright issues surrounding the song, he doggedly pursued Matilda through Queensland, across Australia and, ultimately, to the USA. Magoffin made a number of important contributions to the song’s history, though as Lindner shows, like most Matilda researchers, he got one or two things wrong as well. Nevertheless, his work has also been the basis of the Waltzing Matilda Centre at Winton, dedicated to preserving and representing the history of the song.

Folkies will be familiar with another important figure in the debate. The late and much missed Dennis O’Keeffe advanced the story by investigating family traditions about the song and linking it closely with violent events of the 1890s shearers’ strike in his Waltzing Matilda: The Secret History of Australia’s Favourite Song (2012). Lindner’s own findings mean he isn’t convinced by that argument but acknowledges the value of O’Keeffe’s contribution to the scholarship of the song.

Many others have also had a crack at solving the mystery, putting forward various theories and speculations. But Lindner aims to avoid supposition and myth in favour of cold, hard facts. Not too much escapes his steely eye. He combs old train timetables, ships’ passenger lists, letters, diaries and even considers a skull in the Queensland Police Museum to build his case. From all this evidence, he establishes a chronology for the creation and early diffusion of the lyrically sparse and – let’s be honest – pretty silly ditty about a swaggie knocking off a sheep and throwing himself in the billabong when the squatter and the cops turn up.

The rudimentary lyric of our great song is one of its many intriguing characteristics. I once had a literary colleague who studied the words of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and concluded that it was nearly empty of semantic content. It was such a minimal story, told in so few words, that it was – almost – meaningless. We can take this either to mean that it’s one of the slightest pieces of literature ever scribbled, or that Paterson was a genius of narrative compression. Whatever, in my view, this is the secret of the song’s lyrical success. It is such an empty vessel that, like a cliché, it can be filled with just about any meaning we care to pour in – or out, as many have.

But that’s just my take on the song’s curious appeal. Lindner has nobbled the facts on behalf of us all. Apart from those invested in the tourism appeal of ‘Matilda country’ and a handful of researchers, not many people will give a flying jumbuck about his findings, alas. But anyone with even the faintest interest in the intriguing history of this amazingly durable ditty should ‘grab one with glee’ from any good bookshop or from the publisher.

Even after his research and writing epic, Lindner is still interested in the song, noting that ‘the history of the origins of Waltzing Matilda remains incomplete’, and is keen to hear from anyone with something to contribute to its ever-expanding mythology. He can be contacted at waltzingmatildahistory@gmail.com .You can also follow developments on Facebook at W.Benjamin Lindner, Author .

GS

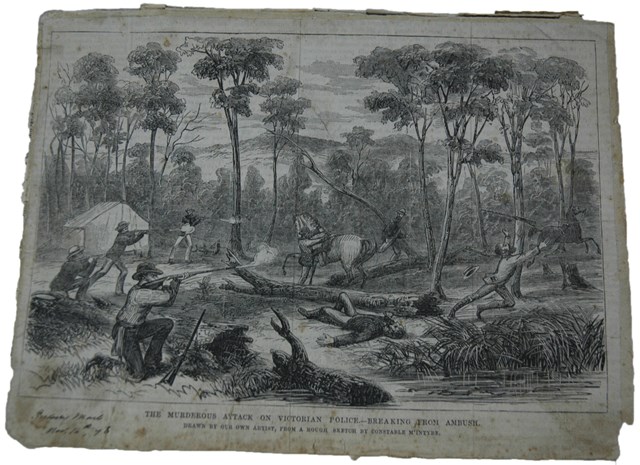

Sydney Mail, November 16, 1878.

Sydney Mail, November 16, 1878.