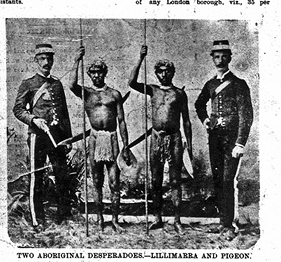

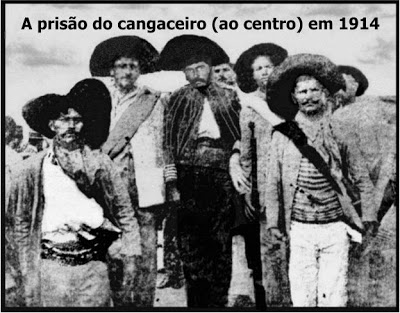

Lampião and some of his cangaceiros. Lampião is left of centre, to the right of him is Maria Bonita. The distinctive leather hats with upturned brims and leather clothes can be seen. The men have Mauser rifles, a great deal of ammunition and several have long peixeira knives thrust though their waist-belts.

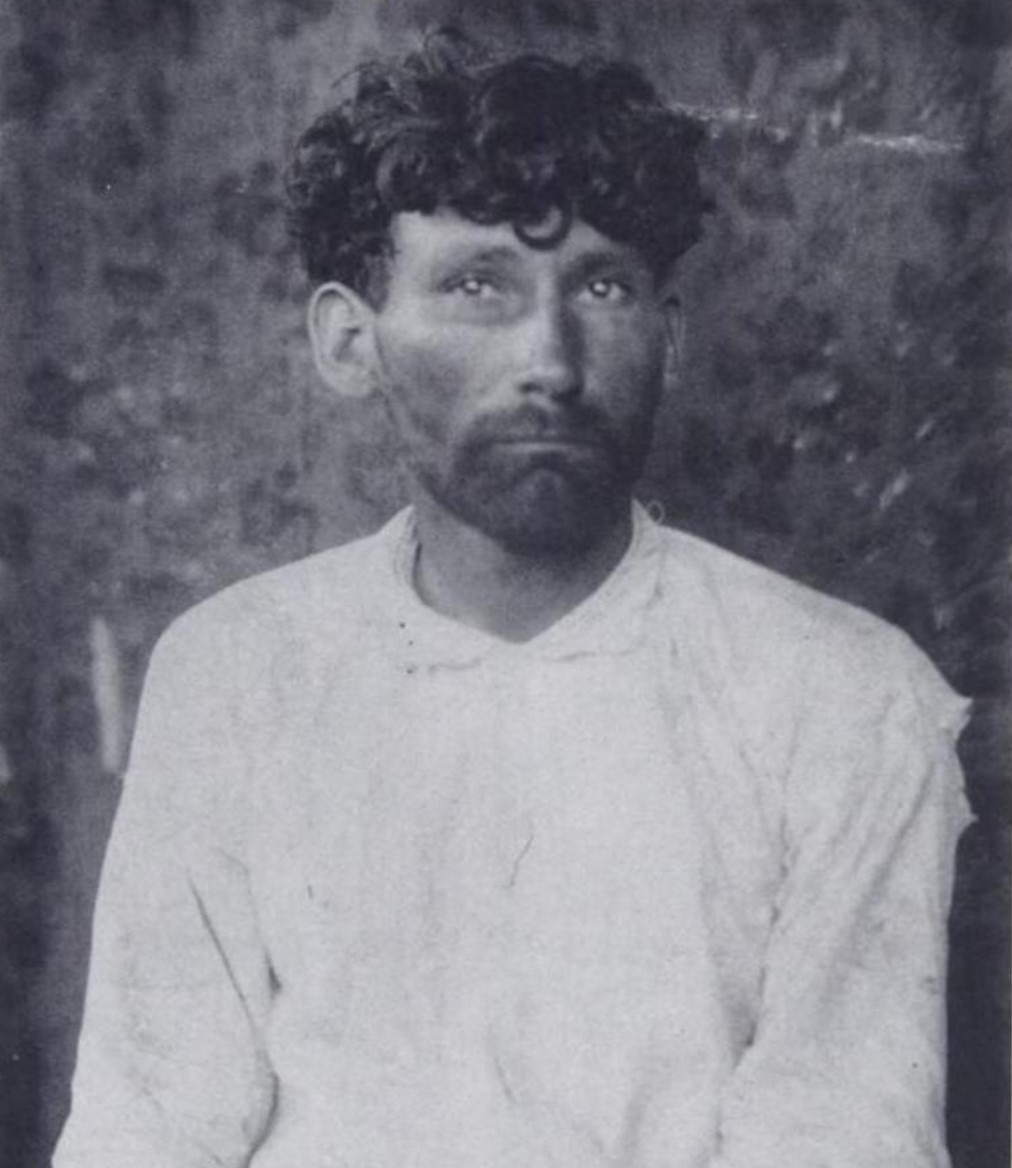

Under his cangaçeiro or bandit name of Lampião – ‘The Lamp’ – Virgulino Ferreira da Silva (1897-1938) followed a nearly twenty-year career of banditry in the Brazilian backlands from before the age of twenty until his grisly death in 1938.

Known as Lampião from his reputed ability to light up the darkness with rapid fire from a lever-action Winchester rifle, his gang’s gang’s first major attack was very much in the Robin Hood mould.

With around fifty men, Virgulino attacked the home of a wealthy aristocratic widow with good political connections. This was profitable and gained the outlaw the immediate attention of the press. His legend now began.

Over the next sixteen years and through several states, Lampião and his various gangs fought pitched battles with police and the volantes, or ‘flying squads’ formed especially to hunt down bandits. They kidnapped police, politicians, judges, the wealthy and the not so wealthy demanding and usually receiving hefty ransoms for their safe return. Towns and farms were plundered, travellers robbed, and sometimes murdered.

As the years passed, Lampião became increasingly savage in his actions, which included torture and humiliation of enemies and informers as well as raping several women. A number of unfortunates were castrated at his orders and he is said to have gouged out the eyes of one poor man in front of his wife and children. He then shot his victim dead through the empty eye sockets. Other atrocities are recorded and documented.[i]

The reality of Lampião’s banditry was therefore very much at odds with the benign image of Robin Hood. Although he professed strict rules about violence and rape, Lampião was feared as a cruel and sometimes sadistic killer, not only of those who opposed him, including peasants, but also of his own men who offended in some way. Over the course of his bandit life Lampião’s power and wealth grew, though most of this seems to have been used in the expensive business of maintaining a band almost continually on the run.

In 1926 he had a flirtation with the politics of his time and place, being given a commission as ‘Captain’ by one group of revolutionaries, together with a promise of amnesty when they came to power. In return, the bandit was to hunt down and eliminate one of their enemies. Lampião soon returned to his bandit ways, but from then retained the title of ‘Captain Silvino’.

Periods of pillage and plunder were followed by times of partying and celebration. Lampião was a noted party-thrower, his wealth allowing him to entertain his friends and allies in style. He was also a flashy dresser in the colourful style universally favoured by cangaçeiros. Distinctive upturned hat, scarf, crossed bandoliers of bullets, rings, boots and liberal applications of eau de cologne and hair pomade, allowing friend and foe alike to smell their presence. The list of possessions made at Lampião’s death included a hat and chinstrap adorned with fifty gold trinkets, rings set with precious stones, gold coins and medallions. His weapons were set with gold and silver and even his haversacks were heavily embroidered and fastened with gold and silver buttons.[ii]

Lampião’s success as a Robin Hood figure despite his cruelties, was largely due to his network of connections at various levels of backlands society and his ability to manipulate the outlaw hero code. He threw coins to the children of the poor and made generous gifts to peasants suffering from droughts and other hardships. He usually kept a tight rein on the carnal instincts of his men and he knew how to use the media. As one of Lampião’s historians put it, the bandit ‘was not unconcerned with his own image’.[iii]

In addition to playing to the press, Lampião has the distinction of being the first bandit to be filmed in action. While Pancho Villa had been filmed in the field for Barbarous Mexico, a documentary released in 1913, he had assumed the more respectable role of revolutionary general for that piece of propaganda. Lampião’s ten minutes of celluloid immortality show him and his men in their natural bandit habitat. Lampião was an enthusiastic collaborator in this public relations initiative.

A number of feature films have since been made based on Lampião’s legend, including one titled Lampião, Beast of the Northeast (1930). His afterlife is also assisted by the folk ballad tradition and an ongoing series of cordels glamorising the outlaw’s life and death, sold cheaply on the streets, initially in regional centres though today freely available in the larger Brazilian cities.

By 1930 the bandit’s fame had reached The New York Times, which in the following year predictably portrayed him as a Robin Hood. While Lampião evinced little interest in helping the poor, he was able to motivate support and sympathy in both high and low sectors of backlands society. Like some other bandits who were seen as possibly useful tools, if properly managed, he was able to call on the intercession of local political figures and power brokers, notably Padre Cicero for favours, money and shelter. His coiteros, or sympathisers, were not only in the upper echelons, though, and the ‘barefoot coiteros’ as the poorer sympathisers were known, assisted by providing the police and volantes with misleading information about the bandits’ movements.

As in other cases of rural banditry, the sympathisers and families of the outlaws experienced harassment from the police, including imprisonment without trial. In the Brazilian situation, this was exacerbated by the inability of the police to act against the wealthier and more influential individuals who colluded, willingly or otherwise, with Lampião due to their powerful political connections. It was not until a degree of inter-state cooperation between police forces and governments developed in the 1930s that Lampião and other cangaçeiros began to feel serious pressure from the authorities.

The religious currents of the backlands were also an important element of the cangaçeiro. The endemic poverty and devastating droughts that ravaged the region gave rise to numerous extreme and millennial religious movements, some of which became linked with revolutionary political activity. Lampião and many of his followers were deeply pious and came to display religious tokens and images of Padre Cícero on their costumes. These were partly related to the belief that such tokens made them invulnerable to bullets, a belief shared by most other Roman Catholic backlanders. By the time of his death, Lampião had become ‘almost a beato, a kind of holy person common to northeastern Brazil.’[iv] This belief did not save the outlaw from his almost inevitable end.

The ‘king of the backlands’ as he was often dubbed, met his doom in the usual manner of the outlaw hero. Early one fine morning a party of police crept carefully towards the sleeping cangaçeiros. So confident were the outlaws of their safety that they had not bothered to post a guard. ‘Lampião’ was clearly visible, sleeping close by his outlaw bride, Maria Bonita (originally Maria Déia). Deliberatel,y the police took aim. One of the bandits, more awake than the others, sensed something wrong and raised the alarm. The police opened fire on the surprised and confused band. Many of the bandits escaped but Lampião was targeted and fell in the first burst of bullets. Maria Bonita and a few loyal comrades fought to the death.

As the gun smoke cleared, the triumphant police strode into the shattered outlaw camp, checking that the outlaws were all dead. One took out a long, sharp knife of the kind favoured by the backlands outlaws and hacked off Lampião’s head. Then Maria Bonita’s head was also severed from her body. The grisly trophies were placed in a jar of kerosene and ridden through the district, proof that the police had at last killed the great cangaçeiro chieftain. A soldier cut off the hand of one of the dead outlaws, packing the severed body part in his pack so that he could later strip the rings from the dead fingers. In keeping with the savage nature of the cangaçeiro and the embedded cultural notions of honour and dishonour in backlands, Bonita’s body was further humiliated.[v]

In an alternative version of the great bandido’s death, it is said that he and his men had already been betrayed to death by poison when the police arrived at the scene of the final shootout. In 1959 the head of the peasant unions claimed the bespectacled outlaw as a pioneer of agrarian land reform and resister of official injustice.

In the early 1970s historian Billy Jaynes Chandler, in Brazil to research his book on Lampião, was told that the notorious cangaçeiro was not dead at all, but living his life out quietly on a farm somewhere: ‘the majority of backlanders with whom I talked in rural areas and small towns held this opinion’.[vi] The outlaw’s granddaughter has published her own version of Lampião’s life, death and afterlife, and the commemorative structures marking the place of his death are the site of considerable touristic and carnivalesque interest.

According to an Al Jazeera report of early 2007, the outlaw now ‘features in a new TV mini-series, one of Brazil’s most famous singers will wear a costume of Maria Bonita at this year’s carnival and another samba school will parade with a huge puppet of the legendary north-easterner.’[vii]

Betrayed, butchered, beheaded and beatified, Lampião’s already powerful legend has long outlived him and shows no signs of fading away.

NOTES

[i] See Chandler, B., The Bandit King: Lampião of Brazil, Texas A&M University Press, College Station and London, 1978.

[ii] Hobsbawm, Bandits, 2000, p. 92.

[iii] Chandler, B., The Bandit King, p. 68.

[iv] Chandler, B., The Bandit King, p. 208.

[v] Chandler, B., The Bandit King p. 226, quoting an eyewitness he interviewed, note 24.

[vi] Chandler, B., The Bandit King, p. 240.

[vii] http://english.aljazeera.net/news/archive/archive?ArchiveId=18847, accessed February 2007.