Tag Archives: Graham Seal

AUSTRALIA’S GREATEST STORIES

Tall tales and colourful characters, from ancient times to today; these are the stories that reveal what makes us distinctively Australian.

Some of the world’s oldest stories are told beneath Australian skies. Master storyteller Graham Seal takes us on a journey through time, from ancient narratives recounted across generations to the symbols and myths that resonate with Australians today.

He uncovers tales of ancient floods and volcanic eruptions, and shows us Australia’s own silk road. He locates the real Crocodile Dundee and explores the truth behind the legend of the Pilliga Princess. He retells old favourites such as the great flood at Gundagai, the boundary rider’s wife and the Australian who invented the first military tank, and presents little known figures like mailman Jimmy, who carried the post barefoot across the Nullarbor Plain, architect Edith Emery and Paddy the Poet, as well as the unusual sporting techniques of the Gumboot Tortoise.

These yarns of ratbags, rebels, heroes and villains, unsettling legends and clever creations reveal that it’s the small, human stories that, together, make up the greater story of Australia and its people.

AUSTRALIA’S GREATEST STORIES

DEFYING THE SYSTEM IN SALEM, 1661

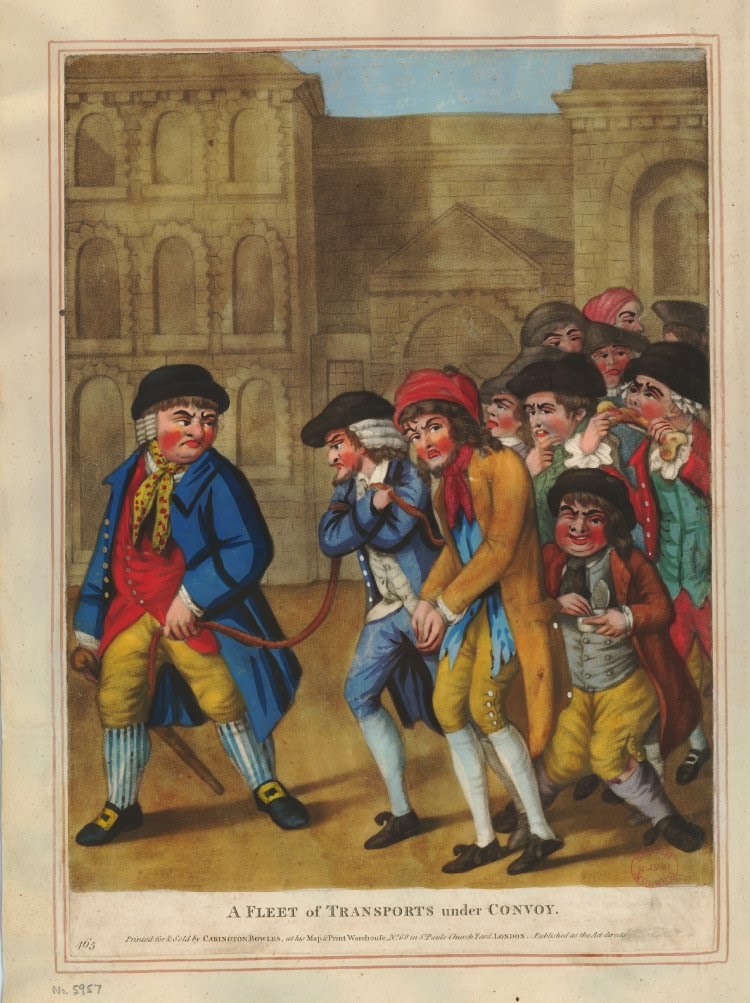

In the seventeenth century, those unfortunate enough to be transported from Britain to the American colonies were sometimes sold to their colonial masters in exchange for cattle or corn. They were not slaves but the conditions in which they laboured were slave-like. Some fought back.

Will Downing and Phillip Welch were before the Salem Quarterly Court of June 26, 1661. They were there for ‘absolutely refusing to serve’ their master, Samuel Symonds, any longer. Seven years earlier, Symonds agreed to pay the master of the ship Goodfellow ‘26li.[pounds] in merchantable corn or live cattle’ due before the end of the following October for the two young men kidnapped from their beds in their own country. They were neither convicts or indentured servants and were almost certainly sold illegally into servitude. Nevertheless, Will and Phillip had worked their master’s fields ever since. And he insisted that he had paid good value for them to do so for nine years, not seven.

One Sunday evening in March 1661, Will and Phillip joined the Symonds family in the parlour for prayer, as usual. Before the family and their servants began to worship, Phillip declared to his master ‘We will worke with you, or for you, noe longer.’ Symonds sarcastically inquired if they were not working what would they do – ‘play?’

Phillip and Will stood their ground. They had served Symonds and his family for the seven years they believed to be their penance for simply being in the wrong place at the time Cromwell’s soldiers were scouring their area for victims. Symonds told them that they were obliged to work for him unless they ran away, a crime with severe punishment. They did not wish to flee; instead they pleaded ‘If you will free us, we will plant your corne, & mende your fences, & if you will pay us as other men, but we will not worke with you upon the same termes, or conditions as before.’

This must have been a memorable moment in the life of the family and its servants. All had been living and working cheek-by-jowl and praying regularly together for seven years. There was some talk about business difficulties as Symonds sought to make his servants see what he considered to be sense. His wife backed him up, saying this was not a good time to bring up the subject of money. But the young men remained adamant. When their master asked them to begin prayers together, they refused. Next morning Symonds summoned the local constable to his home, demanding that the rebellious servants be ‘secured.’ The constable wondered whether it was necessary for the men to be taken away, but Symonds insisted a warrant be served on them and that they should be paraded before the court. Which they duly were.

Now William and Phillip had a chance to state their case: ‘We were brought out of or owne Country, contrary to our owne wills & minds, & sold here unto Mr. Symonds, by ye master of the Ship, Mr. Dill, but what Agreement was made betweene Mr. Symonds & ye Said master, was neuer Acted by our Consent or knowledge, yet notwithstanding we haue indeauored to do him ye best seruice wee Could these seuen Compleat yeeres …’

William and Phillip considered they had already served their time, and more, because the usual practice of transport ship masters was to sell their stolen human cargoes in Barbados for only four years servitude. But now for seven years the two men had labored on Samuel Symonds’ ten acres of corn ‘And for our seruice, we haue noe Callings nor wages, but meat & Cloths.’

For his part, Symonds testified that he had made a bargain with the shipmaster and he had the ‘covenant’, or contract, to prove it. There was a supporting deposition from the shipmaster who said he had sold Symonds ‘two of the Irish youths I brought over by order of the State of England.’

Some other servants gave evidence. One man who had been kidnapped and transported with Will and Phillip described how they had all been rounded up against their will ‘weeping and Crying, because they were stollen from theyr frends.’ Some of Symonds’s own servants testified to the resentment of Phillip and Will against their situation and their determination to be free. Phillip reportedly said at one point that if Symonds would give him the same share of his estate as he would give his own children, then he would continue to serve.

The intensely personal nature of the relationships of master, family and servants in the Symonds household is clear in these testimonies. But the court, rightly or not, found the arrangement was legal and decreed that Will and Phillip should continue to serve until May 1663. An appeal was notified immediately but the two men agreed to work for Symonds until a date for the hearing could be set. He was bound to give them leave to attend.[i]

Whether this appeal was ever heard is not known. Possibly the full nine years were served before it could be and Will and Phillip were finally unbound. If so, they could then sell their labour in an open market and start the families they wished for in the New World.

From Condemned: The Transported Men, Women and Children Who Built Britain’s Empire

Notes

[i] Salem Quarterly Court. Salem, Massachusetts. June 25, 1661. Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, vol. II, 1656-1662, pp. 298ff at https://archive.org/stream/recordsandfiles00dowgoog#page/n307/mode/2up, accessed December 20, 2017. Welch’s proper forename was Phillip, as noted in the court records. Some references to these records claim that the youths were referred to as ‘slaves’ – they were not, see Jennie Jeppesen, ‘Within the protection of law’: debating the Australian convict-as-slave narrative’, History Australia, vol 16, issue 3, 2019, at https://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/TYGCVFDNDUFDAY5NSGNN/full?target=10.1080%2F14490854.2019.1636674&, accessed November 2019.

JUST OUT FOR XMAS – GREAT AUSTRALIAN PLACES

Funny, curious and downright astonishing stories from across a big country

Wherever you go in Australia, you’ll stumble across traces of ancient settlement, remnants of exploration, yarns from the roaring days of gold and bushranging, unexplained events and a never-ending cast of eccentric characters. Read all about it here

TRACKING MATILDA – A CONTINUING CONUNDRUM

Landscape with Swagman (also known as The swagman’s camp by a billabong), painting by Gordon Coutts, oil on canvas, 35.6 x 45.7 cm stretcher; 55.0 x 65.2 x 7.7 cm frame : 0 – Whole; 35 x 45 cm Art Gallery of NSW

Sometimes said to be the world’s most recorded song, the origins of Australia’s accidental anthem, ‘Waltzing Matilda’, has troubled historians and folklorists for a century or so. Just when was it first composed. In what circumstances, where and by whom?

Any number of competing and conflicting theories have been put forward in what seems to be a never-ending flow of books on the subject. Now, W Benjamin Lindner has come up with the most definitive answer to date. Applying the forensic skills of a criminal barrister and a rigorous historical approach to a decidedly ‘two pipe problem’, as Sherlock Holmes might have put it, Lindner’s detective work has convincingly solved the case. It’s all in his Waltzing Matilda: Australia’s Accidental Anthem. A Forensic History (Boolarong Press, 2019).

Not wanting to spoil the story, I won’t give away his conclusion, so you’ll need to check out the book to find the answer. Despite its deep engagement with archival records and the other dry-as-dust stuff that historians like to engage with, it is a good read. While it sets out to prove a particular and important chronological point about the composition of the song, it necessarily tells the human stories of the people most closely involved with it, at the time, and later.

These are, of course, the two main characters, A B ‘Banjo’ Paterson and Christina Macpherson. Paterson thought so little of his dashed-off lyric that he sold the rights to his publisher for five pounds and hardly ever talked about it again. Repurposing a catchy Scots tune, often said to be one of the most recorded songs of all time, Christina Macpherson, mostly got lost in the condescension of posterity. But now she is confirmed in her proper place as the composer of our national song.

And there is a supporting cast of often-colourful other characters who were in on the original events behind the song, as well as later writers who put their efforts towards working out exactly what happened when and where. These include Sydney May, the first person to take an interest, starting seriously in the 1940s. He was misled by some of the accounts he collected but gets the credit for setting the Matilda hunt waltzing.

Then there was the no-nonsense bushman, Richard Magoffin, raised near the legendary site of composition, Dagworth Station. With a commendable disdain for academic historians and the complex copyright issues surrounding the song, he doggedly pursued Matilda through Queensland, across Australia and, ultimately, to the USA. Magoffin made a number of important contributions to the song’s history, though as Lindner shows, like most Matilda researchers, he got one or two things wrong as well. Nevertheless, his work has also been the basis of the Waltzing Matilda Centre at Winton, dedicated to preserving and representing the history of the song.

Folkies will be familiar with another important figure in the debate. The late and much missed Dennis O’Keeffe advanced the story by investigating family traditions about the song and linking it closely with violent events of the 1890s shearers’ strike in his Waltzing Matilda: The Secret History of Australia’s Favourite Song (2012). Lindner’s own findings mean he isn’t convinced by that argument but acknowledges the value of O’Keeffe’s contribution to the scholarship of the song.

Many others have also had a crack at solving the mystery, putting forward various theories and speculations. But Lindner aims to avoid supposition and myth in favour of cold, hard facts. Not too much escapes his steely eye. He combs old train timetables, ships’ passenger lists, letters, diaries and even considers a skull in the Queensland Police Museum to build his case. From all this evidence, he establishes a chronology for the creation and early diffusion of the lyrically sparse and – let’s be honest – pretty silly ditty about a swaggie knocking off a sheep and throwing himself in the billabong when the squatter and the cops turn up.

The rudimentary lyric of our great song is one of its many intriguing characteristics. I once had a literary colleague who studied the words of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and concluded that it was nearly empty of semantic content. It was such a minimal story, told in so few words, that it was – almost – meaningless. We can take this either to mean that it’s one of the slightest pieces of literature ever scribbled, or that Paterson was a genius of narrative compression. Whatever, in my view, this is the secret of the song’s lyrical success. It is such an empty vessel that, like a cliché, it can be filled with just about any meaning we care to pour in – or out, as many have.

But that’s just my take on the song’s curious appeal. Lindner has nobbled the facts on behalf of us all. Apart from those invested in the tourism appeal of ‘Matilda country’ and a handful of researchers, not many people will give a flying jumbuck about his findings, alas. But anyone with even the faintest interest in the intriguing history of this amazingly durable ditty should ‘grab one with glee’ from any good bookshop or from the publisher.

Even after his research and writing epic, Lindner is still interested in the song, noting that ‘the history of the origins of Waltzing Matilda remains incomplete’, and is keen to hear from anyone with something to contribute to its ever-expanding mythology. He can be contacted at waltzingmatildahistory@gmail.com .You can also follow developments on Facebook at W.Benjamin Lindner, Author .

GS