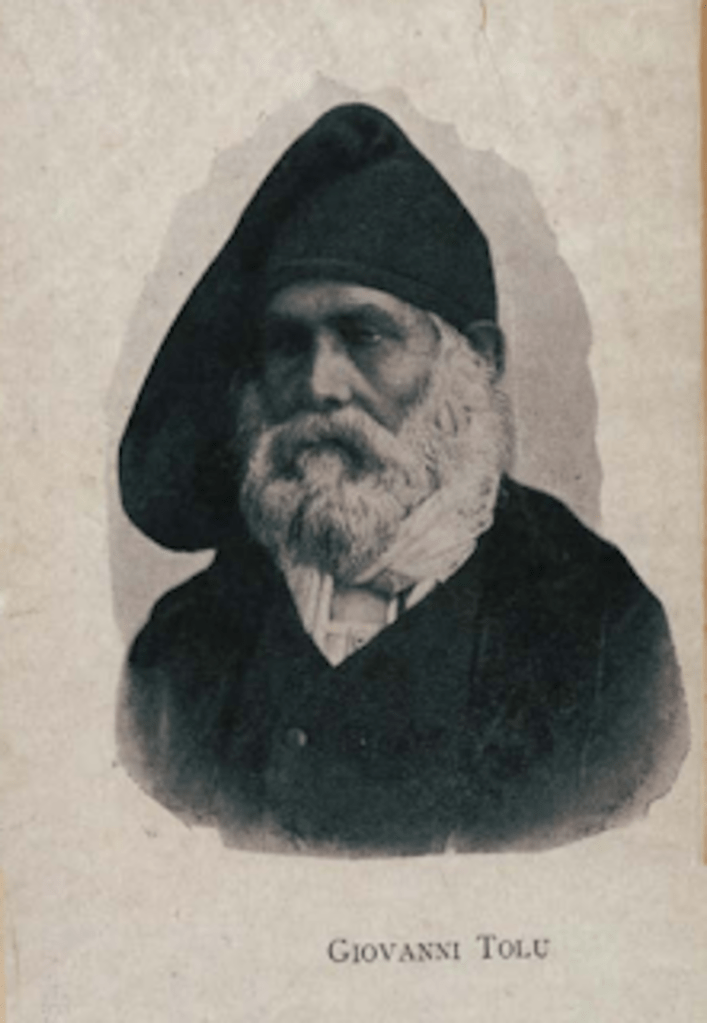

Ritratto di Giovanni Tolu eseguito a Sassari dal fotografo Averardo Lori e tratto dal libro di Enrico Costa del 1897

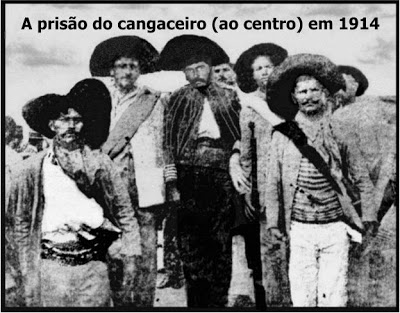

As a boy, the neo-Marxist philosopher and writer, Antonio Gramsci was fascinated by the tales he heard of Giovanni Tolu, the Sardinian bandit. Gramsci went on to a celebrated career, dying in a fascist prison in 1937. Amongst other things, he was an influential theorist of power. Tolu was one of the powerless. Little-known, today, his story is a classic example of the outlaw hero, or ‘social bandit’.

The lofty granite mountains of Sardinia, groves of olives and grapes, scrubland and forested pathways are impenetrable to those who do not know them. Steep valleys and chasms complete this lonely landscape, ideal for bandits. But it was the fractured politics and economic conditions of the island that for centuries made it a byword for bandits.

Giovanni Tolu’s (1822-1896) banditry began in 1850. He was a hard-working and respectable farmer who came into conflict with the local priest, a man named Pittui. Smitten by the priest’s maid, Maria Francesca Meloni Ru, Tolu eloped with her in 1850. Marriage and almost everything else was controlled by the church then and when Pittui found the couple, the pregnant Maria was dragged back to her parents’ home. Enraged and insulted, Tolu later attacked the priest in the street, beating him almost to death. This dire act initiated his thirty or-so year bandit career.

Despite beating up the priest, Tolu was deeply religious and superstitious. He used violence like a good social bandit should – only when necessary and to defend himself. Like many other bandits in Catholic cultures, he also claimed to have always sought divine guidance before murdering, as his biographer described:

‘One day he decided to murder a certain Salvatoro Moro. As I went to his house … I begged the Mother of God to enlighten me and to show me whether this man really deserved death. I also commended my soul to God in case I should be surprised and killed by my enemy’. Tolu apparently received the answer he sought: ‘After I had slain Moro I loaded my gun afresh, after which I said a ‘Hail Mary’ and prayed for the repose of the departed soul. In this way I learned that I had killed the body but not the soul of my enemy.’[1]

Tolu also murdered one of his accomplices who betrayed him. Despite these killings, he had the reputation of a good bandit. He was pursued for thirty years but managed to elude all those who came after him, killing several Carabinieri. He was later reunited with his and Maria’s grown-up daughter and lived a more or less respectable, and highly respected, life among a supportive regional community until his arrest in 1880. He was tried in a local court for murder but acquitted because he was acting in self-defence.

Shortly before his death, Tolu is said to have delivered his life story to the Sardinian lawyer and writer, Enrico Costa. As Costa tells it, he was sitting in his garden one sunny day when the then 74-year-old brigand appeared and handed him a manuscript, saying ‘I want … to give in this way a warning to my colleagues, a lesson to flighty young men and a word of advice as to the manner ln which the government should treat the poor people’.

Unlikely as this incident is – Tolu was illiterate – Costa turned his story into a book that was popular throughout Italy. Although much romanticised, there is no doubt that Tolu was considered a friend of the Sardinian poor and that they actively supported him in his bandit life. Tolu did not leave to see his life in book form, he died in 1896, the year before Costa’s book appeared[2] and became a popular hit in Italy.

[1] Aspen Daily Times, 2 March 1898, p. 3

[2] Giovanni Tolu, Wikipedia, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Tolu, accessed February 2024.