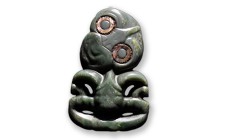

Cropped from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-32986578., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Large collections of bones and body parts lie in dark corners of Australian, American and European scientific institutions. They are the remains of First Nations people acquired during colonisation and shipped to medical establishments, private collectors and museums for preservation, study or exhibition. It is thought that 10 000 or more of these corpses or part corpses were sent to Britain alone and possibly thousands more to other countries.

This grisly catalogue, sometimes called ‘the first stolen generation’, was assembled during the nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries by a puzzling assortment of individuals with a variety of motivations. Sometimes the impetus was money. Sometimes it was what is now seen as a misguided sense of contributing to the advancement of science. Always it was simple racial prejudice based on the flawed belief that Indigenous Australians were some sort of ‘missing link’ between modern and prehistoric humanity.

One of the most active body thieves was William Ramsay Smith, a Scottish doctor who became the coroner of South Australia in the 1890s. He gathered Indigenous remains from many sources, including asylums, prisons and elsewhere. Skeletons, heads and other body parts were sent to Ramsay Smith’s alma mater, Edinburgh University, where his friend, D J Cunningham, Professor of Anatomy, further desecrated them in the name of science.

When the body of a popular local Ngarrindjeri man known as ‘Tommy Smith’ ( Poltpalingada Booboorowie) disappeared while under Ramsay Smith’s control, an inquiry was established in 1903. Ramsay Smith, or someone under his authority, had filled Tommy’s coffin with sandbags. He had then dissected the body and sent the parts to Edinburgh.[i] Gruesome evidence was also given of heads kept in kerosene tins and of a going black market body snatching rate of ten pounds for a skeleton. Ramsay Smith was reprimanded but suffered no lasting damage to his reputation and continued as the state coroner. He also continued his close interest in First Nations bodies. When he died in 1937 more than a hundred human skulls were discovered at his house.

Ramsay Smith was only one of many bone collectors either trading or acquiring remains for what they usually claimed were scientific, medical or anthropological research. Beneath this delusion lurked the pernicious idea, derived largely from Charles Darwin’s theories on evolution, that European culture was the most developed and advanced ‘civilisation’ in the world. First Nations people were considered to be at the beginning of a hypothetical chain of evolution and so, went the scientific thinking of the time, should be closely studied. Researchers needed body parts to investigate and there was also a morbid curiosity among private collectors for examples of what they considered exotic lifestyles, including skins displaying customary markings, pieces of skeleton – one man’s skull was made into a sugar bowl – and, of course, heads. Full skeletons of adults and children were taken from graves and morgues, boxed up and despatched to waiting recipients across the seas.

Dark as these practices were, even more reprehensible parts of the Indigenous body trade depended on frontier violence. In April 1816, a group of Gandangara people was attacked by a military force at Appin, NSW. Fourteen or more men, women and children died, including the leader, Cannabayagal. According to an eyewitness, he and two other warriors were hanged from a tree. The soldiers then ‘cut off the heads and brought them to Sydney, where the Government paid 30s and a gallon of rum each for them.’[ii] When the National Museum of Australia received three repatriated skulls from the University of Edinburgh, one was that of Cannabayagal.[iii]

The unsanctioned removal of remains is a source of ongoing grief and trauma for First Nations communities. Many are anxious to have the remains of their ancestors returned so they can be given proper burials according to law and custom. Ongoing efforts to ensure that stolen body parts are returned to their country have had limited success. While the Australian government supports repatriation, some overseas institutions have been uncooperative in agreeing to returns. There are also practical difficulties in identifying remains and in deciding on the most appropriate way to honour them should they be returned to their First Nations descendants.

Here are some links to news stories about some recent repatriations:

From Austria:

From the Smithsonian Museum, USA:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-04/indigenous-remains-repatriated-from-smithsonian/101272318

From Manchester Museum, England:

NOTES

[i] Adelaide AZ, ‘William Smith’s part in Adelaide trading of Aboriginal people’s bodies exposed by 1903 Tommy Walker scandal’, (from ABC Radio National The History Listen), https://adelaideaz.com/articles/coroner-william-smith-s-part-in-adelaide-trade-in-aboriginal-people-s-bodies-exposed-by-tommy-walker-scandal-in-1903, accessed June 2023.

[ii] Grace Karskens, ‘Appin massacre’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2015, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/appin_massacre, accessed June 2023.

[iii] Paul Daley, ‘Restless Indigenous Remains’, Meanjin Vol 73, No 1, 2014, https://meanjin.com.au/essays/restless-indigenous-remains/, accessed June 2023.