Author Archives: Graham Seal

CONDEMNED REVIEWS

Condemned is picking up a good few reviews in the BBC History Magazine, the Literary Review (UK), Australian Book Review, Crikey and elsewhere. A few quotes:

‘a powerful account of how coerced migration built the British Empire is contained in Condemned’

‘Incisive and moving’

Methodist Recorder (UK), May 2021

‘A brilliant and moving work’

‘What good history can do, and what it needs to be to be good, is shown by Australian historian Graham Seal’s Condemned’

‘It is a rip-snorter of a book, as well as scholarly history’

Guy Rundle, Crikey, 18 September 2021

Purchase hardback, e-book, audio book or paperback (Australia only) at:

Book Details

HOLY GRAILS!

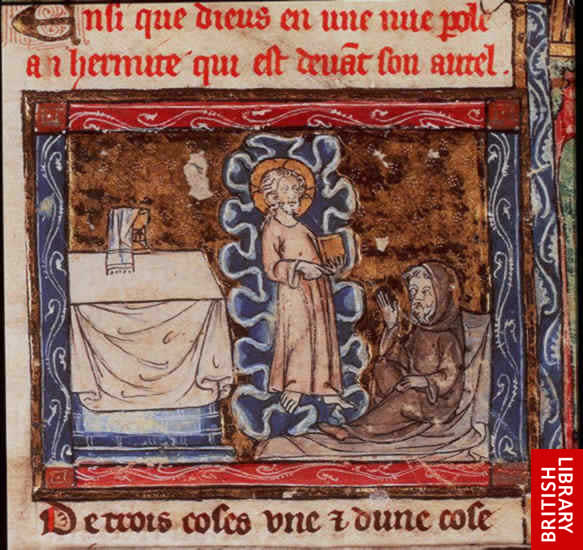

Christ appears to a hermit in a vision, holding a book containing the true history of the Holy Grail. From History of the Holy Grail, French manuscript, early 14th century

Copyright © The British Library Board

There’s a lot of them about, Holy Grails, that is. But one in Spain has an intriguing tale to tell.

The venerable Christian relic known as the Cup of Christ, the Lord’s Chalice and, most evocatively, ‘The Holy Grail’ is the centre of a twisting tale of history and myth. Every facet of its corporeality – shape, colour, size – is uncertain, as is its origins. It is said, variously, to have been the cup or plate used by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper; to have been the bowl used to collect Christ’s blood as he died on the Cross, or both. Then again, it might just be a symbol encoding the mysteries and meanings of the Holy Communion.

We first hear of this relic in medieval Europe where it appears in a number of romances from around the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. This is also the context in which we first hear of the involvement of the Knights Templar in the guardianship of the Grail, a notion that has fed a fecund flow of often farcical fiction right up to the present day. By the fifteenth century it melded into the Celtic Arthurian legends then very much in vogue at court and wherever people could afford books and were able to read them, or have them read aloud. Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485) is the main vehicle for this transformation. In all these variations of the tale, the Grail is located not in the Middle East but in Europe.

How the Grail actually got from its original location in Jerusalem to Europe is a similarly slippery story. One version is that it was brought by the disciple, Peter, when he went there to bring the gospel to the west. This one, not surprisingly, seems to have at least the tacit approval of the Roman Catholic church given Peter’s significance in its founding.

Another, more folkloric tradition, concerns Joseph of Arimathea, the man who is said to have taken responsibility for the transmission of the dead Jesus to the disciples who interred him in Joseph’s garden in a man-made cave. In this version, of which there are several variants, the Grail is usually said to have been a wooden cup taken to England by Joseph, or his followers, where a Christian institution was founded at Glastonbury. This strand of the legend, which may only date from the late nineteenth century[1] also continues to have potency in the modern era as a variety of people seeking spiritual awareness and confirmation, as well as Christians, actively venerate the Glastonbury area, with its intriguing pre-Christian resonances of standing stones and paganism in general.

None of these stories have any credible historical evidence to support them. Like the obsession of the Nazis with aspects of the Cathar version of the legend,[2] they are purely the blended outcomes of belief and fictioneering, producing a potent and enduring myth.

But, relatively recently, another unexpected strand has been added to the rich narrative of the Holy Grail. In 2006 and 2010, a number of early Islamic manuscripts were said to have been discovered in Egypt and translated. They provide potentially verifiable evidence of the history of one particular object identified as the Holy Grail by Islamic sources as early as 400CE. According to Margarita Torres Sevilla and José Miguel Ortega Del Río, the academic authors of Kings of the Grail, an object long identified as the Holy Grail in its place of imputed was kept in Jerusalem for the first thousand years or so of its existence. There, it was visited and venerated by pilgrim Christians for centuries.

Jerusalem was under Muslim control at this point and around 1053-54 a Caliph took the Grail and gifted it to a Muslim ruler in Spain. This man wished to develop good diplomatic relations with the Christian Ferdinand 1 of León and decided to send the object to him. By then the object, described as a stone cup, was said to have medicinal powers. The great Muslim leader, Saladin ((Salah-ad-din), would later play a part in this version of the Grail story, using a ‘fine shard’ previously struck from the object to cure his daughter’s illness. The authors of the book use these documents and other evidence to trace the journey of the Grail to where, they argue, is its current resting place, the Basilica of San Isadoro in León.[3]

So, we now have a new and, it seems, authoritative historical identification of the resting place of the Holy Grail. Not Dan Brown’s Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland; not Rennes-le-Château in Cathar country; and not in the glowing mysteries of the Arthurian romances. It’s in Spain.

Whatever we might think of this argument, remembering that it is made by academics from the region, it seems that this line of Grail legend has some serious historical cred. Far more than any of the many other Grails around the world, including several in Britain and Ireland, some in Italy, one in Vienna, and another in America, among others.

Why does it all matter? For Christians, the answer is obvious. The Grail is a relic as closely associated with the body and death of Jesus Christ as possible. It’s up there with the True Cross, the reed used to give him water and the sponge used to cruelly whet his lips with vinegar as he died. As the authors of Kings of the Grail show, these relics were exhibited in the Temple together with their version of the Grail for centuries.

Interestingly, the Grail does not seem to have been accorded any more significance in this period than the other sacred items, until around the time that it was sent off to Europe for some diplomatic ingratiation. It may be that we owe the evolution of the Holy Grail into Christendom’s most sacred relic to the power politics of the Muslim world as much as the romancing of medieval European troubadours and writers.

[1] S. Baring-Gould, A Book of The West: Being an Introduction to Devon and Cornwall (2 Volumes, Methuen 1899; A Book of Cornwall, Second Edition 1902, New Edition, 1906.

A W Smith, “‘And Did Those Feet…?’: The ‘Legend’ of Christ’s Visit to Britain” Folklore 100.1 (1989), pp. 63–83.

[2] Umberto Eco, The Book of Legendary Lands, Maclehose, 2013. Chapter 8 ‘The Migrations of the Grail’ on Otto Rahn’s Nazi fantastications and also good on other aspects of Grail legendry. See also chapter 14 on the modern crypto-historical invention of The Priory of Syon and the alleged bloodline of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene, as popularised in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.

[3] Margarita Torres Sevilla and José Miguel Ortega Del Río, Kings of the Grail: Tracing the Historical Journey of the Cup of Christ to Modern-Day Spain, The Overlook Press, New York, 2015. Translated from the Spanish edition of 2014 by Rosie Marteau.

A LETTER FROM YOUR ROBBER – JAMES MACLAINE TO HORACE WALPOLE, 1749

Bandits, highwaymen and bushrangers, among other outlaw types, are great letter-writers. Badmen Billy the Kid and Jesse James wrote to the press. Bushranger Ned Kelly wrote, or probably dictated, the lenghty Jerilderie Letter, justifying his crimes, while the the Sicilian bandit Salvatore Guiliano even wrote several letters to the American President. Others also penned challenges to the authorities trying to capture them.

One eighteenth-century highwayman, James MacLaine (various spellings) even wrote to one of his victims, the eminent Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, who MacLaine and his accomplice, Plunket(t), robbed one night in London’s then dodgy Hyde Park. Here it is, a tiny masterpiece of affected courtesy, bravado and defiance, the very essence of the ‘Gentleman highwayman’ image that MacLaine affected:

Date

1749

Sir

friday Evening [Nov. 10, 1749].

seeing an advertisement in the papers of to Day giveing an account of your being Rob’d by two Highway men on wedensday night last in Hyde Parke and during the time a Pistol being fired whether Intended or Accidentally was Doubtfull Oblidges Us to take this Method of assureing you that it was the latter and by no means Design’d Either to hurt or frighten you for tho’ we are Reduced by the misfortunes of the world and obliged to have Recourse to this method of getting money Yet we have Humanity Enough not to take any bodys life where there is Not a Nessecety for it.

we have likewise seen the advertisem[en]t offering a Reward of twenty Guineas for your watch and sealls which are very safe and which you shall have with your sword and the coach mans watch for fourty Guineas and Not a shilling less as I very well know the Value of them and how to dispose of them to the best advantage therefor Expects as I have given You the preference that you’ll be Expeditious in your answering this which must be in the daily advertiser of monday; and now s[i]r to convince you that we are not Destitute of Honour Our selves if you will Comply with the above terms and pawn your Honour in the publick papers that you will punctually pay the fourty Guineas after you have Reced the things and not by any means

Endeavour to apprehend or hurt Us I say if you will agree to all these particulars we Desire that you’ll send one of your Serv[an]ts on Monday Night Next between seven and Eight o clock to Tyburn and let him be leaning ag[ain]st One of the pillers with a white hankerchif in his hand by way of signall where and at which time we will meet him and Deliver him the things All safe and in an hour after we will Expect him at the same place to pay us the money

Now s[i]r if by any Means we find that you Endeavour to betray Us (which we shall goe prepaird against) and in the attempt should even suceed we should leave such friends behind us who has a personall knowledge of you as would for ever seek your Destruction if you occasion ours but if you agree to the above be assured you nor none belownging to you shall Receive any or the least Injury further as we depend upon your Honour for the punctual paym[en]t of the Cash if you should in that Decieve us the Concaquence may be fattall to you–

if you agree to the above terms I shall expect your answer in the following words in Mondays Daily Advertiser–Whereas I Reced a letter Dated friday Evening last sign’d A:B: and C:D: the Contents of which I promise in the most sollemn manner upon my Honour strictly to comply with. to which you are to sign your name–if you have anything to object ag[ain]st any of the above proposalls we Desire that you’ll let us know them in the Most Obscure way you Can in mondays paper but if we find no notice taken of it then they will be sold a tuesday morning for Exportation3

A:B: & C:D:

P: s:

the same footman that was behind the Chariot when Rob’d will be Most Agreeable to Us as we Intend Repaying him a triffle we took from him–

Addressed: To the Hon[oura]ble Horatio Walpole Esq[ui]r[e]

[James Maclaine and — Plunket]

Source: Supplement to the Letters of Horace Walpole, ed. Paget Toynbee, 3 vols, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1918–1925), III, pp. 132–135 (Lightly edited for blog-friendly reading).

CONDEMNED is now released

CONDEMNED is now released in UK and Australia. Reviews and reader responses are good.

It will shortly be released in USA, together with the audio book.

To purchase any of the print editions, the e-book or the audio book, please go to

or any online book seller or your local bookshop.

JACK – A TRUE TALE

Jack was the last child born into a working-class family of Canterbury, England in 1929. There were two older brothers and three older sisters. According to family recollections, the boy was a bit of a handful for his ageing parents and seems to have been mostly reared by his sisters.

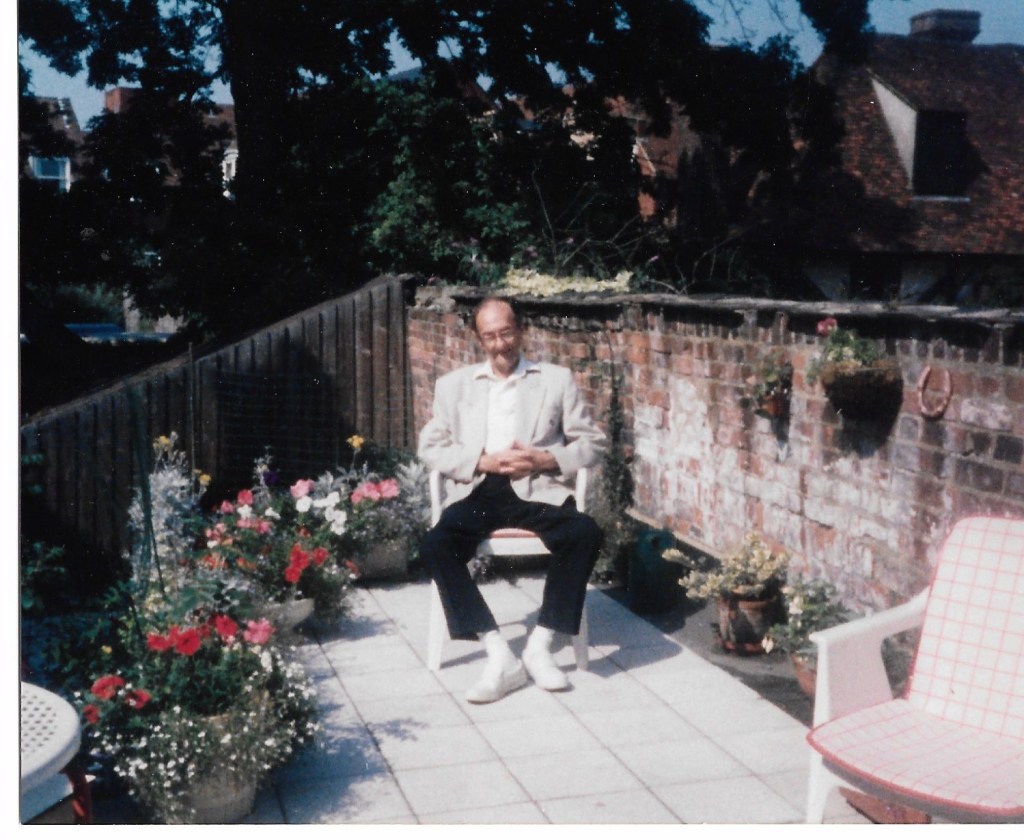

Jack playing at his flat in Bromley, c. 1980s.

The pivotal moment of his life came in late May and early June 1942, the Luftwaffe firebombed Canterbury Cathedral and parts of the ancient city. This brutally pointless act was one of the barbarisms known as the ‘Baedeker Raids’. The complete destruction of Coventry cathedral is nowadays the best-known consequence of these raids and was revenged several years later in equally brutal act of revenge by the allied firebombing of Dresden in 1945.

In Canterbury, fortunately, the damage was much less severe, largely through the bravery of the volunteer firewatchers who waited on the roof of the great monument, picking up and throwing down to the ground enormously dangerous phosphorous firebombs, often as their fuses were burning. The night sky around the cathedral and the city was ablaze with bright chandelier flares and the incendiary bombs that followed them down.

On every night of the raids, young Jack rushed to the bottom of the garden of the family terrace home, transfixed by the flames, the noise and the anti-aircraft fire. They said he was never quite the same again.

In August the following year, Jack was placed on probation for stealing money. He was subsequently referred to a child guidance clinic but by October 1944 he was held at the Philanthropic Society’s Approved School at Redhill, again for stealing money. After finishing school, he worked in various jobs as a labourer, errand boy and lift porter.

In November 1946, he enlisted in the RAF as an Aircraftman, stationed at Cottesmore Royal Airforce Station, Rutland. Eighteen months later, while on leave, he was arraigned at the Kent Assizes. Jack had been arrested for setting fire to the Canterbury Probation Office and, in a separate incident, a motor car.

It turned out that Jack had already torched four other targets in Canterbury and another four at Cottesmore, including a Nissen hut used as a cinema and a firing range. He was pronounced insane and admitted to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in July 1948. Today, he would probably be diagnosed with autism. Jack was nineteen years old.

According to the sparse records released by Broadmoor, Jack weighed eight stone seven pounds and was five feet seven-and-a-half inches tall on admission. He had fair hair, hazel eyes and was described as ‘pale and thin.’ He went to Block 7 for patients under close supervision. Here, he was diagnosed as schizophrenic, together with a ‘disordered personality’ and learning disabilities. Family members were allowed to write and visit and, from 1949, began regularly petitioning for a discharge, unsuccessfully.

In 1951, Jack went to Block 5 for convalescing patients and by 1955 he was declared free of mental illness, though still suffering from an unspecified personality disorder, seemingly due to his occasionally disruptive behavior and a lack of insight into his crimes. Discharge requests continued to be denied as he was thought to be a high reoffending risk.

A new Mental Health Act began in 1959, allowing for tribunals to assess discharge requests. Jack’s first two tribunals were unsuccessful, but in 1966 the third recommended a discharge to a local hospital. This was overruled by the Home Office, though he was moved to the ‘parole block’ that year, where he began to join in communal and constructive activities. He contributed to the hospital’s newspaper, the Broadmoor Chronicle, and took a very active and vocal role in the Broadmoor cricket team.

Up to this point, Jack had worked mainly as a cleaner, now he was employed in the handicraft room and became a member of the block committee. He continued his interest in bowls, table tennis and gardening, as well as cricket, and was an excellent self-taught pianist. In the parole block he became known to his fellow inmates by the nickname ‘Rasher’, possibly because of his fondness for bacon.

After another tribunal, Jack was finally discharged – with conditions – into the care of family members in October 1968. Courtesy of the Home Office, he had done his twenty years. But Jack was still not completely free, there were five years of monitoring conditions attached to his liberty.

He was sent to a clerical position at the Southern Electricity Board but left after a few months to take up a succession of jobs as a labourer, car cleaner, then a short stint at Woolworths, all punctuated by periods of unemployment. In September 1971, Jack joined the Civil Service as a messenger. His discharge conditions ended in December 1974, and Broadmoor had no further hold on his life. He moved out from the family and lived independently from that time onwards, mostly in Bromley.

Despite the bonds of affection, Jack’s relationship with the family had been severed by prison and was strained in freedom. He rarely attended family gatherings, though he was a surprisingly cheery jokester. Slight, sharp and faintly bird-like, he chain-smoked – rollies, not tailor-mades – a habit he picked up in Broadmoor. Jack was a self-taught master of the piano keys and had an encyclopedic knowledge of his passion, the cricket. He dressed neatly, lived an austere life and died alone in 1993.

Jack, probably in his back yard at Bromley. The upturned horseshoe on the brick wall is for luck.

BANDIT LANDS 11 – The Little Angel

*

Angelo Duca was born in the town of San Gregoria Magno in the province of Salerno around 1734. His parents were probably tenant farmers and he received no education, though was considered a leader among his schoolmates. By hard work and application Duca was able by the age of twenty to make enough to buy a small block of land on which he built himself a house. This was a considerable accomplishment and the young man looked set for a prosperous and rewarding life.

But the local landholder, Francesco Carraciolo, possessor of several titles including Duke, took offence at the young shepherd’s small plot of land within his otherwise lordly domain and began amusing himself by trespassing upon the property, much to the futile irritation of the struggling owner. This situation had been in place for some time when Duca’s young nephew inadvertently strayed across the boundary into the duke’s land and was set upon by one of the duke’s gamekeepers. Angelo was outraged and confronted the gamekeeper, demanding the return of the boy’s jacket, which, in accordance with the practice of the time, the duke’s man had retained until a forfeit was paid. There was an argument, escalating into gunplay, firstly by the gamekeeper and then by Angelo who shot and killed one of the duke’s horses. This unfortunate act sealed Angelo’s fate.

He attempted to approach the duke’s administrator with an undertaking to pay compensation for the horse and increase the workdays he was obliged to provide to the duke’s estate each year, as well as the tithe he was required to provide at harvest time. His representations were rejected and the duke had an injunction brought against Angelo that involved the forfeit of his house and land. Angelo attempted to gain the intercession of a more fair-minded relative of the duke, but this only made matters worse and Angelo now had only one option left. He must ‘go in to the hills’ and become a bandit. As Benedetto Croce, the first historian to seriously study Duca’s case put it: ‘public opinion was not wrong in considering him unjustly persecuted’.

Duca joined the band of Tommaso Freda, a violent brigand, learning the tricks of the trade. When Freda was executed by his own men for the price on his head, Duca probably became the leader, perhaps having his nickname of ‘little angel’ bestowed at this time. Unlike Freda though, Angiolillo insisted on strict discipline among his men and was transparently honest in dividing the shares of captured booty, taking only the same as his men, an almost unheard-of equality among brigands. Operating mainly in the mountainous north of Basilicata in southern Italy and surrounding regions, ‘the little angel’ was reputed never to have killed without justification and, in legend at least, murdered no one at all. His main method of obtaining funds was said to be by extorting it from those able to pay, usually through polite threatening letters.

His legendry includes a tale of how he robbed a bishop on his way to Naples. Angiolillo asked the cleric how much money he had and was told that the man possessed a thousand gold coins. The bandit then asked how long the bishop would be in Naples and was told that he would be there for one month. Saying that he would only need half that amount to accommodate himself for that period of time, Angiolillo relieved him of five hundred gold coins saying he was happy to take only that amount and wished him well for the remainder of his journey.

In one story Angiolillo relieves a wealthy Benedictine abbot of half his store, dividing the booty between his own band, poor peasants and providing the dowry for a young girl. As a woman who could not secure a dowry at this time and place was usually condemned to a life of prostitution, this is an especially significant outlaw hero action and one with which Angiolillo is frequently credited in his folklore. He is also said to have established his own court, taking the role of the magistrate to settle local disputes, nearly always favouring the poor. He righted wrongs against discriminated priests and forced farmers and administrators to reduce the price of corn so that the poor might be fed.

On another occasion he invaded the banquet of the Duke of Ascoli, relieving the nobles of gold and food which, according to his ballad:

Then he went down, and for the ladies and the poor,

He had a dinner of good things prepared,

And said: ‘If the lords are feasting,

So too must poverty feast!’.

In another Angiolillo legend the great bandit comes across a poor man being dragged to gaol because he cannot pay back the money he owes the usurer. Angiolillo first releases the man, then confronts the usurer, inflicting a moralistic speech upon him and then burning his records and taking all his money. This he, of course, distributes among the poor. These and many other Robin Hood-like actions, real or not, earned Duca the traditional honoured brigand title of ‘King of the Countryside’.

Angiolillo ’s afterlife was further polished by his numerous victories against the forces sent to hunt him down, most notably at Calitri where he and eleven men roundly thrashed a force of thirty-seven soldiers. These escapades and his increasingly flamboyant style, which included having glittering uniforms made for his men and himself, all contributed to the growth and spread of his fame and by all accounts he was treated as near-royalty by the people of the region and provided the essential sympathy and support required to keep all outlaws at large.

In common with many other outlaw heroes of myth and history, Angiolillo was deeply religious. This also caused him to believe that he was magically or divinely protected from danger and harm. He supposedly wore a magic ring that warded off bullets, a useful protection commemorated in at least one folktale. Another of his legends emphasises the universal skill of the noble robber to fool his enemies by disguise.

One of the most commonly-told oral traditions of Duca, told both to feet-on-the-ground historians Croce in the late nineteenth century and, eighty years later, to researcher Paul Angiolillo (no relation to Duca), focuses the outlaw’s legend. Once, seated inconspicuously in a tavern the outlaw overheard a full regiment of soldiers boasting how they would defeat the notorious brigand. He was so enraged that he revealed himself and challenged the soldiers to capture him. Recovering from their astonishment, the soldiers rushed him. The outlaw grabbed a length of hard-dried codfish and laid about them as they came, forcing them all to run away.

Angiolillo’s end came in 1784 and conformed to the pattern of the outlaw hero. Betrayed by a member of his gang, he was finally run to ground in the Capuchin monastery of Muro Lucano. Wounded himself, and with another wounded accomplice, Angiolillo was trapped in the monastery tower and burned out by the soldiers. His companion was taken but told the soldiers that his leader was dead, a ruse they initially believed.

But then Angiolillo made a dramatic reappearance, falling to the ground from a great height and injuring himself as he landed. In the confusion and in his disguise, he was able to walk through the line of soldiers and take shelter in an aqueduct. Alas, a young boy saw him and alerted the troops. At this point, according to legend, Angiolillo’s magic ring had fallen off, thus explaining his capture.

The outlaws were taken to Salerno and held awaiting trial. So popular was Angiolillo that many volunteered to defend him in court. But the King decreed that the dangerously popular outlaw was to be hanged without the formality of a trial, an action that would later be strongly criticised by the Sardinian ambassador in a report to his government on the administration of the Kingdom of Naples just two years later. Angiolillo’s body was drawn and quartered, the various grisly parts being publicly displayed in those parts of the country where his depredations had been most frequent.

Angiolillo’s ballads further embellished the considerable legend of his life and a contemporary reported in the early 1790s that the Neapolitans ‘look upon him as a martyr, who perished as a victim of his love for the people.’ His songs were in oral tradition until at least the end of the nineteenth century and continued to circulate in street pamphlets during the early twentieth century. A number of writers, including Dumas, romanticised the real and attributed deeds of Angelo Duca, ‘the little angel’ who became ‘King of the Countryside’ in late eighteenth century southern Italy.

SOURCES:

Croce, B, Angiolillo (Angelo Duca): Capo di Banditi, Pierro, Naples, 1892.

Paul F. Angiolillo, A Criminal as Hero: Angelo Duca, Regents Press of Kansas, Lawrence, c1979.

Guiseppe Goran, Mémoires secrets at critiques des cours, des goveurnementsts, et des moeurs des princpaux états de l’Italie, Paris, 1793.

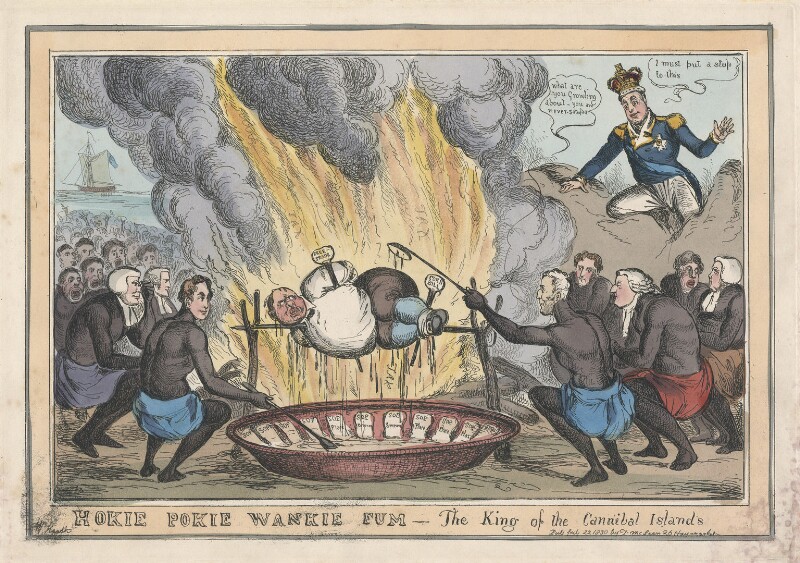

KING OF THE CANNIBAL ISLANDS

hand-coloured etching, published 22 July 1830. 10 1/8 in. x 14 1/4 in. (256 mm x 362 mm) plate size; 11 in. x 16 5/8 in. (279 mm x 422 mm) paper size. Bequeathed by Sir Edward Dillon Lott du Cann, 2018. National Portrait Gallery. Used with permission Under CC Licence.

*

Oh, have you heard the news of late,

About a mighty king so great?

If you have not, ’tis in my pate?

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

So began a broadside ballad of the early nineteenth century, a song that would live on in popular culture for generations. Herman Melville knew it, fragments ended up in a mid-twentieth century children’s rhyme and it became a popular folk dance tune.

Who was the King of the Cannibal Islands’, and why was such an inane piece of doggerel so popular for so long?

According to the song, the King was

‘… so tall, near six feet six.

He had a head like Mister Nick’s,

His palace was like Dirty Dick’s,

‘Twas built of mud for want of bricks,

And his name was Poonoowingkewang,

Flibeedee flobeedee-buskeebang;

And a lot of Indians swore they’d hang

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

Hokee pokee wonkee fum,.

Puttee po pee kaihula cum,

Tongaree, wougaree, chiug ring wum,.

The King of the Cannibal Islands.[iv]

The initial cause of the song’s composition was a grisly tale of shipwreck and mystery.

After transporting a cargo of convicts to Sydney Cove in 1809, the Boyd under Captain John Thompson sailed from Sydney in October that year. Aboard were around seventy passengers and crew, including a number of Maori, one a chief’s son named Te Ara. Thompson was keen to obtain some kauri spears to add to his cargo of seal skins, coal, lumber and whale oil. Te Ara recommended Whangaroa where his people lived and where he assured Thompson there were excellent stands of kauri.

The Boyd moored and Te Ara went to greet his kin after a long absence. The Maori came aboard the ship and relations were cordial at first, until Thompson took a small boat party ashore to search for spears. They never returned. The Whangaroa Maori clubbed and axed them all to death. The Maori then rowed out to the Boyd and began to massacre those aboard, dismembering the victims while a few survivors watched in horror from the rigging.

At the end, only five of those aboard the ship escaped the butchery, aided by Te Pahi, a visiting Maori chief from the Bay of Islands apparently shocked at the scene. One survivor was later killed, leaving Ann Morley and her baby, a two-year-old Betsey Boughton and cabin boy Thom Davies in dangerous captivity.

What caused such brutal events?

At some point before the Boyd reached Whangaroa, Te Ara was lashed to a capstan and either flogged or threatened this punishment by Captain Thompson for his refusal to work his passage. He protested that he was a chief’s son and should not be so basely punished but was mocked by the sailors and denied food. This was a loss of face among his people triggering an obligation to take revenge. [i] A dreadful vengeance it was.

According to the rescuers under Alexander Berry who arrived at the scene in December there was evidence of mass cannibalism. As Berry later wrote: ‘The horrid feasting on human flesh which followed would be too shocking for description’.[ii] They also found the charred remains of the Boyd, apparently blown up when the Maori tried unsuccessfully to make use of the muskets and gunpowder aboard. The flames ignited the whale oil and the ship quickly burned and sank, a number of Maori, including, including Te Ara’s father, dying in the conflagration.

Assisted by Maori from the Bay of Islands, Berry secured the safe return of the four survivors as well as the government despatches and private letters carried by the Boyd. Betsey was in a poor condition, crying ‘Mamma, my mamma’.[iii]After threatening the killers with a murder trial in Europe Berry relented, avoiding further bloodletting, though so great were tensions in the region that a planned mission settlement was postponed for several years.

Berry took the remaining four survivors on his ship. They were bound for the Cape of Good Hope but suffered storm damage and eventually ended up in Lima, Peru. Here Mrs Morley died. Davies went to England aboard another ship and the two children went with Berry to Rio de Janeiro and then to Sydney.

Meanwhile, news of the massacre, cannibalism and capture of the survivors fuelled darker emotions. Men from a small fleet of whalers attacked Te Pahi and his people. This seems to have been a complete misunderstanding of the massacre as Te Pahi by most accounts tried to help the Europeans. Berry may have confused the similar names of the two chiefs in his account of what had happened. Up to 60 Maori and one whaler died in this misguided act of revenge. Te Pahi then attacked the Whangaroa Maori and died from wounds dealt in battle.

In later life, Thom Davies returned to New South Wales where he worked for Berry but was drowned on an expedition to the Shoalhaven River with Berry in 1822. Betsey Broughton married well, living until 1891. Mrs Morley’s daughter eventually ran a school in Sydney.

As the story of the Boyd massacre became more widely known in Britain and beyond, it encouraged both shock and humour. The grisly tale of blood, betrayal, cannibalism and survival fuelled the growth of a ‘savage natives’ stereotype that would become the stock in trade of rip-roaring adventures and south seas island concoctions for decades to come. Pamphlets appeared, warning people against migrating to such dangerous places. Popular comic songs like ‘The King of the Cannibal Islands’ were based on this and other colonial encounters, reflecting European attempts to process such dramatic cultural and social differences through absurdity.

[i] New Zealand History, ‘A Frontier of Chaos? The Boyd Incident’, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/maori-european-contact-before-1840/the-boyd-incident

[ii] Augustus Earle, A Narrative of Nine Months’ Residence in New Zealand in 1827, Whitecombe & Tombs Limited, London, 1909, chpt 11 at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11933/11933-h/11933-h.htm#CHAPTER_XI, accessed November 2016.

[iii] Alexander Berry in The Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany, volume 83, 1819, p. 313.

[iv] Eric Ramsden, ‘The Massacre of the Boyd’, The World’s News, 29 April 1939, p. 6, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/137004962?searchTerm=last%20convict%20expiree%20dies&searchLimits=l-australian=y|||l-format=Article|||l-decade=193|||sortby=dateAsc|||l-year=1939|||l-category=Article , accessed February 2021.

[v] National Library of Scotland, http://digital.nls.uk/broadsides/broadside.cfm/id/16439, accessed November 2016.

CONDEMNED: THE TRANSPORTED MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN WHO BUILT BRITAIN’S EMPIRE

Here’s the hardback cover of my upcoming book with Yale University Press, published in UK and USA in May and as a paperback in Australia around the same time.

There’s an audiobook as well. All available on pre-order now.

Condemned came about because the human story of Britain’s transportation system has never been fully told. Historians have researched the legal, political, penal and other aspects of the topic and we now have a good understanding of the operation and impact of transportation in Australia, America, Africa, India and the many other British possessions where men, women and children were sent to labour. Against this background, I wanted to retrieve and tell a few of the life stories of the transported and convey something of how people dealt with such a traumatic experience. Many were broken by it – but many others flourished and made significant contributions to the places of penance to which they were exiled.

My previous work on the transportation was focused on the Australian experience. When I came to look at the much larger picture of imperial transportation, I learned how adroitly Britain had exploited human resources to build and maintain an extensive empire. As I researched further, I began to see that as the penal transportation system declined, one of its main aims was quietly pursued by other means.

Children were among the earliest victims of the system in the seventeenth century. They were again from the nineteenth century through a charitable continuation of transportation. The tens of thousands of orphaned or unwanted girls and boys conveyed to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Southern Africa were not felons. But, like the convicts who preceded them, they were sent to provide labour for developing the empire, as well as the means to populate it further.

An important reason for the eventual abolition of transportation was public opposition to its abuses, injustices and sheer brutality. Later, the evils of child migration were exposed and addressed through public advocacy in those countries where unaccompanied children were subjected to institutionalised terror. The success of these hard-fought campaigns prefigures contemporary human rights and social justice campaigns, such as the Black Lives Matter movement.

The large and long story of transportation, in whatever form, covers much of the globe and spans four centuries. The consequences continue into the present century through lingering historical guilt about convict ancestors and inquiries, apologies and compensation payments to the system’s last victims. Those who were, rightly or wrongly, condemned to the grinding inhumanity of transportation deserve to have their stories heard today.

*

BANDIT LANDS 10 – The Hassanpoulia of Cyprus

(NB: Most diacriticals omitted)

In the 1880s mountainous Paphos was one of the poorer regions of Cyprus. Greek and Turkish Cypriots lived side-by-side under the control of a British administration that had perpetuated the Ottoman system of considering the Turks and Greeks on the island as members of their own ‘nations’, with their own religious, legal and educational institutions. Cyprus had a history of occupation and domination reaching back to the ancient Egyptians so the British, who assumed control in 1878, were just the latest in a long line of colonisers. The actions of the Hassanpoulia (poulia means ‘birds’) as the family confederacy and the other members of its gang were known, came to be seen by both Turkish and Greek Cypriots as a form of revolt against British authority. The British administration certainly perceived the activities of the gang and the considerable sympathy and support they commanded among the dispossessed and disgruntled peasantry, as a potential source of political trouble.

But within a decade of the deaths of the Bullis two distinctly different traditions developed. The Turkish Cypriot tradition continued to present the Bullis as heroic outlaws but in Greek Cypriot epics they are treated much more negatively. The disjunctions between the two traditions reveal both the ambivalence of outlaw heroism and the potency of the tradition itself, as seen in the extent to which the composers and singers of the Greek epics needed to demonise the Bullis.[i]

The events that generated these traditions began in May 1887 when the 19 or-so years old Turkish Hasan Bulli was accused of theft. The accusation was denied and Hasan took to the hills. According to one version of the story he became involved in a feud with another outlaw over Hasan’s uncle’s young wife and was eventually framed and arrested. He soon escaped and continued his lawless existence, still trying to kill his rival. He survived the next eighteen months of attempted betrayals and traps by robbing the local herds and apparently polarising opinion for and against him. Eventually he contracted malaria and, in a weakened state, gave himself up to the police. Convicted and sentenced to death, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, which he served in an untroubled manner for six years, even being allowed the privileges of a trusty.

But in 1894 he heard that his two brothers Kaymakam and Hüseyin had been betrayed and arrested. They had been involved in a Greek-Turkish dispute over a woman and were accused of murder. Hüseyin attempted to escape and join them but was killed by prison guards. His brothers gathered a band of outlaws and survived until their killing or capture and execution in 1896. Large rewards were offered in vain by the British for the capture of the outlaws.

In 1895 the Outlaw’s Proclamation Act was also passed in an attempt to limit the influence of their activities which, whatever their intent, were widely interpreted by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots at the time as being directed against the British. This act was another descendant of the medieval notion of outlawry and effectively subverted the usual legal processes ‘extraordinary powers being given to the Executive to remove from the disturbed districts, persons suspected of assisting and harbouring the outlaws’.[ii] Application of the Act in the districts of Limassol and Paphos involved the arrest and gaoling of the main holders of flocks. The success of the outlaws in eluding capture for so long is a clear testament to their support from the larger populace, as was the necessity to hold their trial elsewhere and to bury their executed remains within the prison walls.

From early in the twentieth century there arose two oral epics about these events and their protagonists – a Greek work of 318 verses and a near-400-verse Turkish work. The Greek poem acknowledges the bravery, escaping and disguising abilities (including dressing as women) of the Hassanpoulia, common features of outlaw hero traditions:

They used to fly like birds

And they used to try a different costume everyday

They used to be dressed like a Turk one day

And like a Greek the next day…

But they are also savage rapists and promiscuous murders rather than revolutionaries and the Muslim Hassanpoulia’s end is attributed to the curse of a Christian priest.

The same events are interpreted quite differently in the Turkish-Cypriot epic. The kidnappings and rapes made much of in the Greek story are rapidly passed over as everyday events. The various murders are portrayed as justified retribution against informers and the Hassanpoulia swear to die fighting rather than surrender to the British overlords:

I died but I did not surrender to the British

and:

Let the British hang me, pity on me

Death is much better for me than this outrage.

The Turkish version is much what might be expected of an outlaw hero tradition from almost anywhere in the world. The hero is wronged, is a great escaper, a brave hero, a friend of his own people and an avenger of their injustice against their oppressors. To fail, he – in this case, ‘they’ – must be betrayed. The importance of female and male honour, while often encountered in other outlaw hero traditions, is especially intense in this culture and forms not only the rationale for most of the criminal activities of all the brothers but is also the pivotal difference between the Turkish and Greek traditions. So important is the moral code of the outlaw hero tradition forbidding the misuse of women, that the events, real or not, are graphically highlighted in the Greek version of the abduction of the Turkish women:

She was sleeping with her husband, when

She was forcefully taken away, and

Almost her poor husband was killed.

They have their turns over her, one by one

Who is going to ask about her, who is she going to complain to

Blood is gushing from her like a fountain…

And also in the Greek version:

Three insatiable monsters suddenly entered the house

They took her away and spent the night somewhere else

At an isolated sheep fold, at a remote cottage

They almost killed her, and tore her breasts.

The Hassanpoulia have continued to play an important cultural role in the fractured politics of Cyprus. While both Greeks and Turks, in Paphos at least, may have seen the outlaws as an expression of their dislike of British rule and supported them accordingly, the increasingly polarised politics of the succeeding century have solidified the opposing interpretations. In the now Greek southern Cyprus the Hassanpoulia are common bandits, while in the northern Turkish sector of the island they are symbols of the popular struggle against colonial oppression.[iii] [iv] [v]

[i] Ismail Bozkurt, ‘Ethnic Perspective in Epics: The Case of Hasan Bulliler, Folklore Vol. 16,http://haldjas.folklore.ee/folklore/vol16/bulliler.pdf, Presented to the ISFNR 2000 Conference, Kenyatta University, July 17th–22nd, 2000.

[ii] Bryant, R., ‘Bandits and ‘Bad Characters’: Law as Anthropological Practice in Cyprus, c. 1900’, Law and History Review vol 21, no 2, Summer 2003, par 55 (online).

[iii] Though see Paul Sant Cassa’s ‘Banditry, Myth and Terror in Cyprus and Other Mediterranean Societies’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol 35, No. 4, Oct. 1993, which argues that ‘the Hassanpoulia were never incorporated in a Cypriot national rhetoric and subsequent Cypriot agonistes modelled themselves on the equally dubious Greek klephts rather than their own home-grown variety’. p. 794.

[iv] At http://www.cypnet.co.uk/ncyprus/culture/hasanbullis/, accessed October 2004. The article is based on the following cited sources: N. Gelen, “Bir Devrin Efsane Kahramanlari: Hasan Bulliler”, Halkin Sesi Matbaasi, Nicosia, 1973, B. Lyssarides, “Hassan Poulis, the Jesse James of Old Cyprus”, Cyprus Weekly, No.815, p.11, G. Serdar, 1571’den 1964’e Kibris Turk Edebiyatinda Gazavetname, Destan, Efsane, Kahramanlik Siiri: Arastirma-Inceleme, Ulus Ofset, Nicosia, 1986, O.Yorgancioglu, Kibris Turk Folkloru, Famagusta, 1980; pp. 91-107.

[v] Lyssarides, B. 1995. ‘Hassan Poullis, The Jesse James of Old Cyprus’,

The Cyprus Weekly, July 14–20.