Author Archives: Graham Seal

LINES OF LIGHT – How Jewish children’s art survived the darkness of the Prague ghetto and Nazi death camps.

A couple of follow-ups to ‘The Bullshit Detection Bureau’:

THE BULLSHIT DETECTION BUREAU

Finding Truth in the Age of Obfuscation

The unwelcome ability of the WWW to amplify error, delusion and straight-out lying has made us all potential victims of falsehood and flim–flam. This includes, but is not limited to, disinformation, misinformation, propaganda, fake news, urbanmyths, rumour, moralpanics advertorials, and more!

Thereare a fewthings you can doto protect yourself from thenonsense.

SOURCES

Wheredoes the informationcome from? Howcan you knowit is it a reliable source andnot someone or somethinghoping to hoodwink you?

Someproviders of information are morereliable than others, usually because they havesome form ofbuilt–in checkingprocess, such as peerreview in the caseof academic research or fact–checking carried out by reputablemedia sources.

Itfollows that the bestsources of independently researched (not unsupported and uninformedopinion or biased market surveys) and objectively evaluated information are universitiesand quality print and/or digital media. Theseare increasingly being broughttogether in quality platforms such asThe Conversation, Aeon and other operationsthat publish quality research with alevel of editorialoversight.

Open–slather platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thelike are finefor chatting but docarry not reliableinformation. They are easilymanipulated by governments wishing to spreadpropaganda or rig elections,by vested commercialinterests and ideological zealots, as recent events have demonstrated.

INTENT

Whenyou access anitem of information,try to workout the intentionof the author/s. Does thewriting try to putyou, the reader,into a particularposition or mindset? Ask yourselfwhy. Are theytrying to convince you ofa point ofview, sell youa product or anidea? Alarm youeven?

Aclassic giveaway in digital messages attempting to frightenyou into doingsomething, like chain letters,drug or otherscares LINK, are these– ! ! ! ! !. Themore of themthat follow a statement, themore you shouldignore it.

Andnever pass themon, as theyalways insist you should. Theirintent is to spreadfear, uncertainty and panic. Why certain individals have aneed for thissort of behavioris a mysterybest left topsychologists. They have alwaysbeen with usbut, again, theWeb has greatlyincreased their ability to spreadthe nonsense they getoff on.

TONE

Thelanguage and style ofthe message are relatedto its intent. If the languageis overheated, intemperate or otherwiseover the topyou can besure the individualwho composed and distributedit is likewise. These messages are designedto play uponour perfectly reasonable fears andare presented as actualexperiences, as in thisemail example from Australiain 2007 (Slightly edited for coherence on thepage):

I was approached yesterday afternoon around 3.30 PM in the Coles parking lot at Noranda by two males, asking what kind of perfume I was wearing. Then they asked if I‘d like to sample some fabulous Scent they were willing to Sell me at a very reasonable rate. I probably would have agreed had I not received an email some weeks ago, warning of this scam.

The men continued to stand between parked cars, I guess to wait for someone else to hit on. I stopped a lady going towards them, I pointed at them and told her about how I was sent an email at Work about someone walking up to you at the malls, in parking lots, and Asking you to sniff perfume that they are selling at a cheap price.

THIS IS NOT PERFUME – IT IS ETHER! When you sniff it, you‘ll pass out and they‘ll take Your wallet, your valuables, and heaven knows what else. If it were not for this email, I probably would have sniffed the perfume“, but thanks to The generosity of an emailing friend, I was spared whatever might Have happened to me, and wanted to do the same for you. These guys hit Sydney and Melbourne 2 weeks ago and now they are doing it in Perth and Queensland.

IF YOU ARE A MAN AND RECEIVE THIS PASS IT ON TO ALL THE WOMEN YOU KNOW!!!

I called the police when I got back to my desk. Like the email says, LET EVERYONE KNOW ABOUT THIS, YOUR FRIENDS, FAMILY, CO– WORKERS,whoever!!!!!

Have the best day of your life!!!!!

Notice how this one begins calmly and with a matter-of-fact, reporting tone. This draws the reader in. But the gradually increasing tone of exclamation mark-assisted hysteria in this message is a reliable indicator of bullshit.

‘FACTS’AND STATS

Accuratenames, numbers, dates and other‘factual’ data have alwaysbeen hard tocome by, whichis why theencyclopedia was invented. Tomes likeEncyclopedia Brittanica and the likehave largely done theway of thedinosaurs. Despite its virtues and crowdediting model, Wikipediais no substitutefor ancient but usuallyaccurate authorities and is susceptibleto special interests, ideologies and goodold–fashioned errors offact.

Infact, Wikipedia represents the best andthe worst ofthe Web. Itsstrengths are also itsweaknesses. Use it withdiscretion. Always check at leasttwo other sourcesof information before committingto information on Wikipedia, especially anything faintly statistical. Preferably find anold–style printsource, useful for facts upto around 2000. Thesewere written by expertsand exhaustively fact–checkedbefore the internet made allinformation slippery.

AUTHORITY

Acommon way of validatinginformation is to haveheard it froma ‘friend’, a friendof a friend’or other apparentlytrustworthy source. We invest highcredibility in those weknow, often unwisely,as they areas susceptible to receivingand transmitting bullshit as anyoneelse.

Urbanmyths (or contemporarylegends) are spread byword of mouth,through the media (printand digital) and throughemail and socialmedia in general. Their validation is oftenthat the storyis true because‘I heard itfrom a friendof a friend’, or something similar. There are innumerableyarns of thistype in circulationand many havebeen for avery long time,providing them with theveneer of authenticity and ‘truth’. How often haveyou heard that anti–Vietnam War protesters spat onreturning veterans? Not only isthere no evidence of this ‘fact’,what information does existsuggests that nothing of thesort ever happenedor, even ifit did, wason a minisculescale.

Legendsof this typeoften provide apparent validation of theirclaims by referring to ahospital, police department, local government authority, etc. (Seethe kidney legendabove, which mentions the police). If you takethe trouble to check– and youshould if you are concerned– you’ll discoverthat these authoritieswill have no record of the allegedevent.

TRUSTNOTHING

Noteven this article. The best defenceagainst obfuscation is a criticalview of everything. Don’t take anyone’s word for anythingwithout validating it for yourself. Even experts make mistakesand suffer fromunconscious biases. Always look for a range of sources and views.

In the end, we are all our own best bullshit detectors.

WRAITH OF THE COPENHAGEN

|

| Copenhagen, 1921 |

YES! THERE IS A MAP

Another lost treasure legend. This one is a beauty, it has pirates, gore, a map and two generations of seekers:

More on proverbs in action today

OLD WISDOM

HISTORY’S FIRST GRUMPY OLD MAN

Do not let a flaunting woman coax and cozen and deceive you: she is after your barn. The man who trusts womankind trust deceivers.

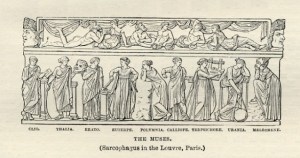

Then I crossed over to Chalcis, to the games of wise Amphidamas where the sons of the great-hearted hero proclaimed and appointed prizes. And there I boast that I gained the victory with a song and carried off an handled tripod which I dedicated to the Muses of Helicon, in the place where they first set me in the way of clear song . . . for the Muses have taught me to sing in marvellous song.

Perses, lay up these things in your heart, and do not let that Strife who delights in mischief hold your heart back from work, while you peep and peer and listen to the wrangles of the court-house. Little concern has he with quarrels and courts who has not a year’s victuals laid up betimes, even that which the earth bears, Demeter’s grain. When you have got plenty of that, you can raise disputes and strive to get another’s goods. But you shall have no second chance to deal so again: nay, let us settle our dispute here with true judgement which is of Zeus and is perfect. For we had already divided our inheritance, but you seized the greater share and carried it off, greatly swelling the glory of our bribe-swallowing lords who love to judge such a cause as this. Fools! They know not how much more the half is than the whole, nor what great advantage there is in mallow and asphodel.

Never make water in the mouths of rivers which flow to the sea, nor yet in springs; but be careful to avoid this. And do not ease yourself in them: it is not well to do this.

… they lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief: miserable age rested not on them; but with legs and arms never failing they made merry with feasting beyond the reach of all evils. When they died, it was as though they were overcome with sleep, and they had all good things; for the fruitful earth unforced bare them fruit abundantly and without stint. They dwelt in ease and peace upon their lands with many good things, rich in flocks and loved by the blessed gods.

It was like the golden race neither in body nor in spirit. A child was brought up at his good mother’s side an hundred years, an utter simpleton, playing childishly in his own home. But when they were full grown and were come to the full measure of their prime, they lived only a little time in sorrow because of their foolishness, for they could not keep from sinning and from wronging one another, nor would they serve the immortals, nor sacrifice on the holy altars of the blessed ones as it is right for men to do wherever they dwell. Then Zeus the son of Cronos was angry and put them away, because they would not give honour to the blessed gods who live on Olympus.

… a brazen race, sprung from ash-trees and it was in no way equal to the silver age, but was terrible and strong. They loved the lamentable works of Ares and deeds of violence; they ate no bread, but were hard of heart like adamant, fearful men. Great was their strength and unconquerable the arms which grew from their shoulders on their strong limbs. Their armour was of bronze, and their houses of bronze, and of bronze were their implements: there was no black iron. These were destroyed by their own hands and passed to the dank house of chill Hades, and left no name: terrible though they were, black Death seized them, and they left the bright light of the sun.

… which was nobler and more righteous, a god-like race of hero-men who are called demi-gods, the race before our own, throughout the boundless earth. Grim war and dread battle destroyed a part of them, some in the land of Cadmus at seven- gated Thebe when they fought for the flocks of Oedipus, and some, when it had brought them in ships over the great sea gulf to Troy for rich-haired Helen’s sake: there death’s end enshrouded a part of them. But to the others father Zeus the son of Cronos gave a living and an abode apart from men, and made them dwell at the ends of earth. And they live untouched by sorrow in the islands of the blessed along the shore of deep swirling Ocean, happy heroes for whom the grain-giving earth bears honey-sweet fruit flourishing thrice a year, far from the deathless gods, and Cronos rules over them; for the father of men and gods released him from his bonds. And these last equally have honour and glory.

… would that I were not among the men of the fifth generation, but either had died before or been born afterwards. For now truly is a race of iron, and men never rest from labour and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night; and the gods shall lay sore trouble upon them. But, notwithstanding, even these shall have some good mingled with their evils. And Zeus will destroy this race of mortal men also when they come to have grey hair on the temples at their birth. The father will not agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guest with his host, nor comrade with comrade; nor will brother be dear to brother as aforetime. Men will dishonour their parents as they grow quickly old, and will carp at them, chiding them with bitter words, hard-hearted they, not knowing the fear of the gods. They will not repay their aged parents the cost their nurture, for might shall be their right: and one man will sack another’s city. There will be no favour for the man who keeps his oath or for the just or for the good; but rather men will praise the evil-doer and his violent dealing. Strength will be right and reverence will cease to be; and the wicked will hurt the worthy man, speaking false words against him, and will swear an oath upon them. Envy, foul-mouthed, delighting in evil, with scowling face, will go along with wretched men one and all. And then Aidos and Nemesis, with their sweet forms wrapped in white robes, will go from the wide-pathed earth and forsake mankind to join the company of the deathless gods: and bitter sorrows will be left for mortal men, and there will be no help against evil.

… then goats are plumpest and wine sweetest; women are most wanton, but men are feeblest, because Sirius parches head and knees and the skin is dry through heat. But at that time let me have a shady rock and wine of Biblis, a clot of curds and milk of drained goats with the flesh of an heifer fed in the woods, that has never calved, and of firstling kids; then also let me drink bright wine, sitting in the shade, when my heart is satisfied with food, and so, turning my head to face the fresh Zephyr, from the everflowing spring which pours down unfouled thrice pour an offering of water, but make a fourth libation of wine.

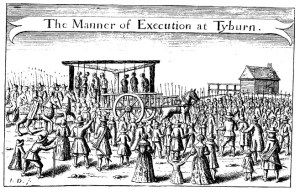

FRUMMAGEMMED, NOOZED AND SCRAGGED – THE LANGUAGE OF EXECUTION

|

| The Tyburn Tree – the permanent gallows at Tyburn, which stood where Marble Arch now stands, about 1680 |

But when we come to TyburnFor going upon the budge,There stands Jack Catch, that son of a whore,That owes us all a grudge.And when that he hath noosed us,And our friends tip him no cole,Oh then he throws us in the cartAnd tumbles us in to the hole.

…in an undaunted Manner; as he mounted the ladder, feeling his right Leg tremble, he stamp’d it down, and looking round about him with an unconcerned Air, he spoke a few Words to the Topsman, then threw himself off, and expir’d in five Minutes.