Could he have been ‘Jack the Ripper? The remarkably evil life of Frederick Deeming is one of the most chilling stories of Australian, and global, crime. Even if he did not commit the Whitechapel murders of 1888, his known slayings make him one of the worst serial killers of the nineteenth century.

Beaten by his unstable father and imbued with fear of damnation by his God-obsessed mother, Frederick Bailey Deeming got off to a bad start in life almost as soon as he was born in Leicestershire, England in 1853. He was already known as ‘Mad Fred’ when he went to sea around the age of sixteen and soon became a cunning criminal. Fraud and false pretences were his favoured offences, though he also thieved from time to time.[i]

With an ability to turn on the charm and a persuasive way with words, the ruggedly handsome young sailor with blue eyes, fair hair and a ginger moustache had little trouble forming serious relationships with respectable women. In 1881 he married Marie James in England. By the middle of the next year he was in Sydney where he had jumped ship and started work as a plumber and gas fitter. By the time Marie arrived to join him he had already served a six-week sentence for stealing gas-burners. The couple would have four children over the next few years during which Deeming briefly ran his own plumbing business until he was declared bankrupt and serving two weeks for committing perjury. In January 1888 he turned up, alone, in Cape Town, South Africa where, using the alias Henry Lawson, he conducted several successful swindles.

Back in England in 1890, and still calling himself Henry Lawson, Deeming bigamously married Helen Matheson, using the proceeds of a fraud to pay for the wedding. Soon after, he had to quickly leave the country and escaped to Uruguay, South America. He was later arrested there, returned to England and given nine months in prison for fraud, though he avoided any charge of bigamy.

After release in 1891, Deeming took another alias, Albert Williams, and rented a house in Rainhill, Lancashire. By this time, his deserted wife and children had tracked him down and Marie revealed her husband’s bigamy to Helen. Apparently too embarrassed at the social stigma this would bring upon her, Helen did not inform the authorities. Deeming, now fearing what else Marie night reveal about him, made an elaborate pretence of reconciliation and convinced her and the children to join him at Rainhill. It was a fatal error.

Shortly after the reconciliation ‘Williams’, now posing as an army officer, married for a third time. The unlucky woman was Emily Mather who, after the expensive wedding, sailed with her new husband to India where he said he had a posting. But Deeming changed the arrangements and the newlyweds went to Melbourne instead. Here they rented a house in Windsor. Always ostentatious, even if mostly with other peoples’ money, the outwardly charming ‘Druin’, as Deeming was now styling himself, soon became well known in the suburb. But in January 1892, he and his third wife disappeared.

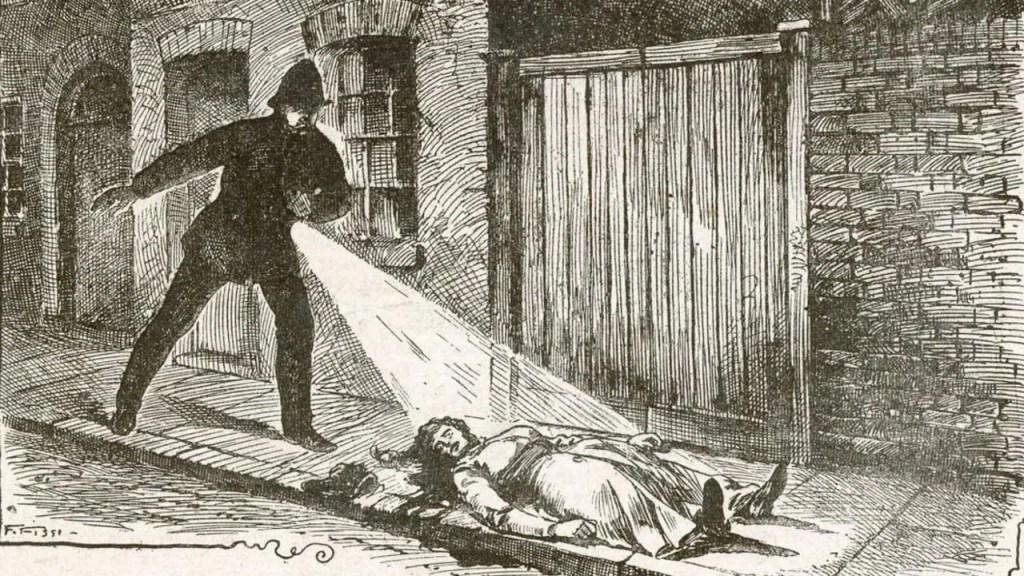

Now, a chain of events began that would lead to Deeming’s eventual downfall. The next tenant in the Windsor house complained of a foul smell in the premises. A hearthstone in the bedroom was pulled up to reveal Emily’s badly decomposed remains. She had been beaten around the head and her throat slashed. In the house police also found a copy of the invitation to the wedding banquet of A O Williams and Helen.

In a little over a week, the police tracked Deeming down to the Western Australian mining town of Southern Cross where he was calling himself Baron Swanston and posing as an engineer. After murdering Emily he had committed some further frauds and sailed to Sydney. There the apparently personable murderer soon convinced another young woman to become his fiancée. He then left for Western Australia, arranging with her to follow him when he was settled.

Deeming’s arrest ignited what would become a national and international press sensation. An English journalist used details from Australian sources to backtrack Deeming to his previous rented premises in Lancashire. The authorities there were prompted to investigate. Under the kitchen floor they found the bodies of Marie and the four children, all with their throats cut. The enormity of Deeming’s crimes was now apparent.

The press certainly thought so and went into one of the regular ‘feeding frenzies’ that have become all too familiar since. A kind of mass public hysteria arose, known as ‘Deemania’. The accused was called ‘a human tiger’ and his actions dubbed ‘the crime of the century’. He would also be described, inaccurately, as ‘ape-like’ and a forensic expert would later claim that his skull was similar to that of a gorilla.[ii]

Although entitled to the presumption of innocence, Deeming was effectively tried and found guilty in the newspapers of the English-speaking world. He was tried for the murder of Emily under the name of ‘Williams’. His defence, which included Alfred Deakin, destined to be an early Australian Prime Minister, argued that the accused had been denied a fair trial, which was probably true. Deeming was almost certainly an epileptic, having suffered from fits for much of his life. He may also have been a schizophrenic fantasist who actually became the identities he invented as he committed his crimes. But after an unwise address to the jury from the dock and some unconvincing psychiatric testimony, he was quickly found guilty and sentenced to death.

After being refused leave to appeal by the Privy Council, Edward Bailey Deeming, alias Albert Williams and at least four other pseudonyms, was hanged on 23 May 1892. Always a poser, he walked to the gallows smoking a cigar. His last words were reportedly ‘Lord, receive my spirit’. Outside the prison wall, twelve thousand people assembled to await the news that the monster was dead.

His death was celebrated in an English children’s street rhyme based on the then popular belief that Deeming was Jack the Ripper:

On the twenty-first of May,

Frederick Deeming passed away;

On the scaffold he did say —

“Ta-ra-da-boom-di-ay!”

“Ta-ra-da-boom-di-ay!”

This is a happy day,

An East End holiday,

The Ripper’s gone away.[iii]

Deeming was undoubtedly guilty of the horrendous murders of his children and two wives, with the likely intent to kill another. But could he have been ‘Jack the Ripper?

In the overheated press speculations on the case, the fact that Deeming’s movements in 1888 were murky, together with the grisly nature of his crimes, led to speculation that he might have been the Whitechapel killer. Some credibility was attached to the claim when Deeming told fellow prisoners that he was the ripper and also expressed a murderous dislike of women. This was based on his venereal infection, probably of syphilis, contracted from a prostitute during his extensive travels. When directly questioned about this on the eve of his execution, deeming refused to confirm or deny the possibility.

But the theory has so many flaws that it is taken seriously by very few.[iv] A major problem is that Deeming’s murders bore little resemblance to the butchery of most of the Whitechapel victims. Nor were the women he killed prostitutes. Unlike the Whitechapel murderer, Deeming was not known to have taken trophies of his victims. Finally, wherever Deeming was during those bloody months of 1888 – probably South Africa – there is no evidence that he was anywhere near London, let alone the east end.

But there is no doubt that he slew Emily, the crime for which he eventually hanged, and that he also killed Marie and his children. He never confessed to any of these murders but while in prison during the lead up to his trial and as he awaited execution, Deeming wrote his autobiography, later destroyed, and poetry, which included the lines:

The Jury listened well to the yarn I had to tell,

But they sent me straight to hell.

From Australia’s Most Infamous Criminals

[i] Barry O. Jones, ‘Deeming, Frederick Bailey (1853–1892)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/deeming-frederick-bailey-5940/text10127, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 26 July 2022.

[ii] The Argus, 25 January 1930, p. 6.

[iii] Larry S Barbee, ‘Frederick Bailey Deeming’, Jack the Ripper Casebook, https://www.casebook.org/ripper_media/book_reviews/non-fiction/cjmorley/48.html, accessed July 2022.

[iv] Over fifty books have been written about Deeming, often revolving around the unlikely belief that he was Jack the Ripper. See Worldcat Identities, ‘Deeming, Frederick Bailey 1853-1892, https://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n2007021186/, accessed July 2022.