She was a slight, short woman, a young adult. He was around fifty years old, built lightly and around 1.7 metres tall. They were both buried in the Willandra Lakes on Paakantji, Ngyiampaa, and Mutthi Mutthi country around forty-two thousand years ago. Mungo Lady’s remains were recovered in 1968 and those of Mungo Man in 1974. Until these discoveries, humans were thought to have occupied Australia for only around ten or twelve thousand years. More recent evidence suggests that the ancestors of First Nations people arrived here much earlier.

Mungo Lady and Mungo Man were buried only around five hundred metres apart yet they did not know each other. Later excavations revealed many more sets of human remains and a community of humans living for generations in the usually well-watered area, hunting, harvesting, procreating, dying and being ritually buried – she by cremation, crushing and interment; he face upwards, hands folded on his lap and his body sprinkled with red ochre. [i] Ancient though these people were, their forebears may have lived in Australia for thirty or more thousand years.

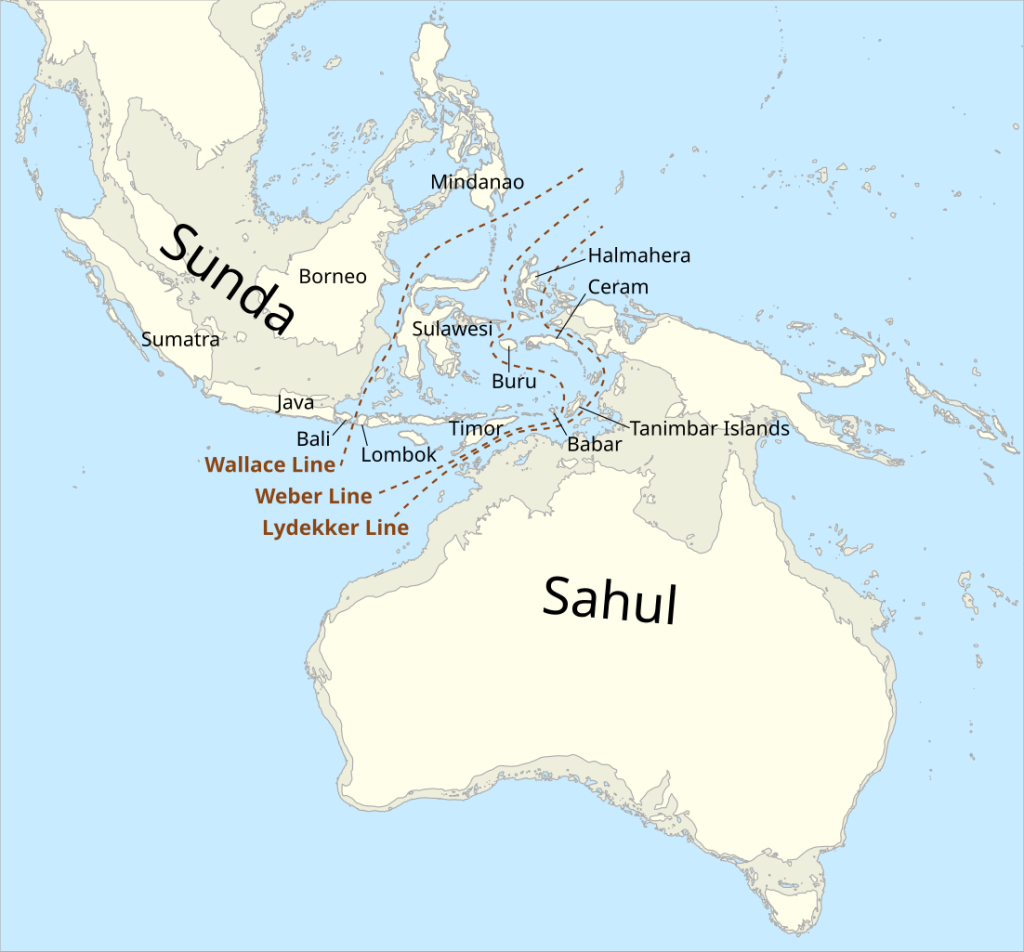

Scientists are rewriting what we thought we knew about early human history and a prehistoric supercontinent called ‘Sahul’ has an outsize role in the story. Existing in the Pleistocene Epoch, from around 2.6 million to around twelve thousand years ago, it consisted of mainland Australia, attached to Tasmania, and to many of the islands we know as Papua New Guinea and to what is now called Timor. From perhaps as long as seventy-five thousand years ago, large groups of technologically sophisticated humans crossed from the northern reaches of the supercontinent to begin the peopling of Australia. More followed at later times, probably by sea, and within around ten thousand years of first arrival the ancestors of the First Nations had reached the southern tip of Sahul.

The routes these first comers travelled on their epic journeys – continental ‘superhighways’ – began in Timor and Papua New Guinea then passed, broadly, along the west and east coasts and through the centre, looping through the Nullarbor and, eventually, reaching Tasmania. There were secondary connecting routes but the superhighways were created by waves of people moving towards and through ‘highly visible terrain’, basically the mountain ranges of the continent. These tracks became trade routes and songlines and often correlate with later stock routes and even modern highways.[ii]

We have long held the idea that Australia and the people living here before colonisation were unknown and isolated from the rest of the world. For many centuries, stories of an unknown continent at the southern end of the globe circulated through the ancient and medieval worlds. Often called ‘the unknown south land’, or ‘terra australis incognita’, this continent was shrouded in mystery and myth. Any people who might live there would necessarily walk upside down, it was said, and there would be strange beasts and flowers growing there – wherever it might be.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, European navigators began to slowly peel back the mysteries of the land as they came into contact with it and, sometimes with its original inhabitants. Gradually, coastlines were charted, the odd river or island was hastily explored and by the time James Cook came to make his celebrated voyage along the east coast in 1770, Europeans had some idea of the size and shape of what we now call Australia. But at this time there was almost complete ignorance of the inland and it was not clear whether Tasmania was attached to the rest of the continent. Answers to those questions would come in time, but the dominant story was that the great south land was completely unknown – other than to its original occupiers – until ‘discovered’ and colonised by Europeans. It followed that there had been no outside contact for millennia. But in recent years, other possibilities have arisen.

The north-west of Arnhem Land has a wealth of rock paintings depicting sea creatures, European sailing ships and other scenes. Among these paintings are two intriguing images that archaeologists believe to be war craft from the Maluku Islands. It has long been known that trepang fishers from the area usually known as Macassar regularly visited and sojourned in Arnhem Land since around 1700.[iii] But these were, as far as we know, peaceful visits by fishing boats. The paintings on the rock shelters of Awunbarna (Mount Borraedaile) show craft with pennants and other indications that they were designed and fitted out for war rather than trade.[iv] To date, no one has found any indications of conflict between First Nations people and whoever might have sailed the warships, but the paintings are evidence of pre-European interactions with people from islands to the north of Australia.

In Queensland’s channel country, the Mithaka have been quarrying stone for seed grinding for several thousand years. These quarries are spread across an area of more than 30 000 square kilometres in which are dwellings and elaborate stone arrangements thought to be of ceremonial significance. The stones are also part of an ancient industrial production and trade system dubbed ‘Australia’s Silk Road’ that runs from the Gulf of Carpentaria to the Flinders Ranges in South Australia.[v] Archaeologist Michael Westaway observes that the route ‘connected large numbers of Aboriginal groups throughout that arid interior area on the eastern margins of the Simpson Desert’ and that ‘You get people interacting all across the continent, exchanging ideas, trading objects and items and ceremonies and songs’.[vi]

It is possible that this trans-continental Silk Road also connected with trade routes beyond Australia. There is strong evidence of interchange between Torres Strait Islanders and what is now Papua New Guinea for over two thousand years.[vii] The discovery of a platypus carved into a sixteenth-century church pew in Portugal and the documented presence of cockatoos in medieval Sicily[viii] suggests that there were links between Australia, south Asia and, ultimately, Southern Europe, for centuries before Europeans began to arrive on the unknown south land.

First Nations people also travelled beyond Australia to islands in the north, even forming family attachments there. These places were linked to other parts of the world through trading networks we are only beginning to uncover, so it would be possible to send Australian wildlife, as well as other items, along these routes. Ongoing research will reveal more information about the pre-modern world and its extensive connections, so the image of an unknown south land might need to be even more radically reshaped. First Australians were not completely isolated though they, and almost everything else about Australia, would remain a mystery to those who came much later. In the many millennia before that there was enough time for even geological and cosmic events to become part of Australia’s story.

From Australia’s Greatest Stories https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/book/Graham-Seal-Australia’s-Greatest-Stories-9781761471131