Scientists have extracted RNA from the extinct Tasmanian tiger. So, could it be resurrected in the future?

Find out all about it here

Find out all about it here

The ships of Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to Australia, “Géographe” and the “Naturaliste”, at Kupang, Timor. State Library of South Australia

In April 1801 French navigator Nicolas Baudin’s expedition was sailing off the south coast of what is now Western Australia. In the spirit of the age, Baudin was making a voyage of scientific investigation, as well as discovery. He was, of course, also spying on the British colony of New South Wales, though that was not verified until much later.[1]

The voyagers hoped not only to find new places and chart new coastlines but also to make contact with any Indigenous inhabitants they encountered. Equipped with his flagship Géographe and Naturaliste, under the command of Jacques Félix Emmanuel Hamelin, he was originally accompanied by a large group of scientists, artists and gardeners, though many of these became too ill to complete the voyage, five dying. Many of Baudin’s sailors were also at various stages of the extended expedition. One was lost in the large expanse of the Indian Ocean Baudin named Geographe Bay.

Or was he?

Timothée Armand Thomas Joseph Ambroise Vasse was born into a bourgeoise family in Dieppe, France in 1774. He grew up and was educated between Rouen, where his father was a legal official, and Dieppe, where members of his extended family lived. During the French Revolution he joined the army, was wounded and later discharged. After a few years as a civil servant, he vanished and joined Baudin’s expedition as a junior assistant helmsman on the Naturaliste. Vasse was in trouble by the time Naturaliste reached Isle de France. Captain Hamelin planned to dismiss him there but lost so many other sailors through desertion that he was forced to keep the troublesome twenty-seven-year-old aboard his ship.

On 30 May 1801, the voyagers encountered what is now Geographe Bay. They landed in small boats and set up camp while the scientists conducted their investigations of the flora and fauna in the area. A few days later, one of the boats was sunk at the Wonnerup Inlet and had to be abandoned. The shore party was rescued but some equipment was left behind.

Three days later, Vasse was aboard a small boat attempting to recover the equipment. But once again the small boat was swamped by the surf. The crew were washed ashore and only saved by a heroic sailor from another boat who swam ashore through the dangerous waters carrying a rope by which the castaways were able to haul themselves into the other boat.

Except for Timothée Vasse. Said to have been drinking, he lost his grip on the lifeline and sank into the surf. With no further sign of him, Vasse was presumed drowned and Hamelin made sail, apparently without bothering to confirm the fatality.

The fate of Timothée Vasse would have been simply another footnote in the long history of lost sailors if not for the rumours. Soon after the return of Baudin’s expedition to France in 1803 Parisians began hearing stories that Vasse had not drowned but had survived and been cast away on a strange and very distant shore. Baudin himself was dead by now, but the official expedition account, written by the zoologist on the expedition Francois Peron, discounted the possibility that Vasse had survived. But the rumours persisted and were published in European newspapers. According to these accounts, Vasse lived with the local people for some years then walked hundreds of kilometres of coast to eventually be picked up by an American whaler, handed to the British and subsequently imprisoned in England.

No other Europeans are known to have visited Geographe Bay until after the foundation of the Swan River colony in 1829. When early settlers came into contact with the Wardandi (Wardanup and other spellings) people of the southwest region they began to hear other stories. In 1838 George Fletcher Moore was told while visiting the Wonnerup area that Vasse did not drown. With the help of the local people, he lived for several years and died of natural causes somewhere between present day Dunsborough and Busselton.

He seems to have remained almost constantly upon the beach, looking out

for the return of his own ship, or the chance arrival of some other. He pined away gradually in anxiety, becoming daily, as the natives express it, weril, weril (thin, thin.) At last they were absent for some time, on a hunting expedition, and on their return they found him lying dead on the beach, within a stone s throw of the water’s edge.

They describe the body as being then swollen and bloated, either from incipient decomposition, or dropsical disease. His remains were not disturbed even for the purpose of burial, and the bones are yet to be seen.[2]

There were other versions of the tale. In one, Vasse was thought to have eventually been murdered. A ‘society in Paris’ was said to be offering a reward for the recovery of his bones – ‘the natives know where they are’, wrote one of the Swan River colony’s early settlers, Georgiana Molloy, in 1841.[3] In another, based on European features observed among Indigenous people around Geographe Bay, it was suggested that Vasse had fathered children with Wardandi women.[4]

Some attempts have since been made to resolve these conflicting possibilities. Among several books and articles on the subject[5] is one written by a descendant of Timothée Vasse. According to Alain Serieyx, family tradition holds that the lost sailor did survive and eventually return to France.[6] The book is a speculative fiction based on this belief but adds another thread to a fascinating tale.

Whether or not Timothée Vasse lived, pined, and died as a lone white man on a distant continent will never be known for sure. Whatever his fate, his memory is preserved in the name of the Vasse River and of the Vasse region of southwestern Australia.

[1] Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby (transl. and eds.), French Designs on Colonial New South Wales: François Péron’s Memoir on the English Settlements in New Holland, Van Diemen’s Land and the Archipelagos of the Great Pacific Ocean, The Friends of the State Library of South Australia Inc., Adelaide, 2014.

[2] The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal 5 May 1838, p. 71.

[3] Alexandra Hasluck, Georgiana Molloy: portrait with background, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1955.

[4] Oldfield, Augustus. “On the Aborigines of Australia.” Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, vol. 3, 1865, pp. 215–98. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3014165. Accessed July 2023, P. 219. Oldfield mistakenly thought Vasse was one of Baudin’s scientists, but his opinion was based on his own observations of the Geographe Bay area.

[5] Thomas Brendan Cullity, Vasse: An Account of the Disappearance of Thomas Timothée Vasse, 1992; Edward Duyker, ‘Timothée Vasse: A Biographical Note’, Institute for the Study of French-Australian Relations, https://www.isfar.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/51_EDWARD-DUYKER-Timoth%C3%A9e-Vasse-A-Biographical-Note.pdf, accessed July 2023;

[6] Alain Serieyx, Wonnerup: the sacred dune, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, c2001, translation [from the French] by David Maguire.

Everyone laughs at something, or someone, though not necessarily the same things or ones. Humour is notoriously culture-specific and often does not translate across ethnic, religious, linguistic and other borders, even those of taste.

On the other hand, global storying is full of tricksters and funsters who carry out a remarkably similar set of pranks, japes and general mischief.

Often, these are designed to puncture the pretensions of the high and mighty, to ridicule the rich and to take the pompous down a peg or two.

Others revolve around the most basic common denominator of bodily functions. A Korean story of a character called ‘General Pumpkin’ belongs to a group of stories concerned with titanic farts, a theme that also appears in German tradition and in the 1001 Nights.

General Pumpkin

The son of a rich man eats nothing but pumpkins. Fields of them. So greedy for pumpkins was the boy that he eventually bankrupted his family. He was not popular in his home village because his gluttonous pumpkin consumption made him fart loudly, frequently and with overpowering odour. When they could no longer stand the stink, they turned the boy out of their village.

The boy wandered from village to village, working frequently because he was so big and string from eating pumpkins and because he only wanted to be paid in pumpkins. But after a few days he always lost these jobs because his titanic farting was too much for everyone to bear.

One day he arrived at a famous and wealthy temple, high up in the mountains. The Abbot saw the large boy and thought that he would be able to help the monks deal with the robbers who were harassing the temple. The robber leader would disguise himself as a traveller and stay at the temple so that he could let his band of brigands in during the night. This had been going on for some time and the monks were sick of losing their property.

So, the Abbott quickly invited the boy inside and asked him what he liked to eat. The monks happily cooked the enormous amount of pumpkins the gluttonous boy demanded, then asked for his help. That night, the robber chief again entered the temple with his usual intention of letting his men inside. He was curious about the many pumpkins he saw and was told that a ‘General Pumpkin’ was staying at the monastery. The robber asked how many men the General had and was told that he was alone and would eat all the pumpkins himself. The robber decided to hold off letting his men into the buildings while he waited to witness this startling sight.

Meanwhile, General Pumpkin told the monks to take their drums to every corner of the monastery and hide until midnight. As the robber chief waited, inside the monastery and his men massed outside the walls, a sudden rumble thundered through the premises filling the air with a dreadful stench. General Pumpkin had farted. The monks pounded on their drums and at the same time, a great wind sprang up and blew down the monastery walls, killing the robber chief and all his men.

The Abbott and the monks were grateful, despite the stink, and allowed General Pumpkin to live at the monastery and supplied him with as many pumpkins as he wanted. He lived there for many years and in old age was asked to help three rich young brothers rid their family of a white tiger that has killed their father. In the process of helping, General Pumpkin accidentally let go one of his great farts, killing the tiger. Unfortunately, so explosive was the fart that it killed him as well. The three brothers found his remains in a pool of shit. They gave him a fitting burial and mourned him as they did their father.[i]

General Pumpkin’s humorous gluttony is put to good purpose, though eventually ends his life. The incongruous nature of the story is found in many other forms of folk humour.

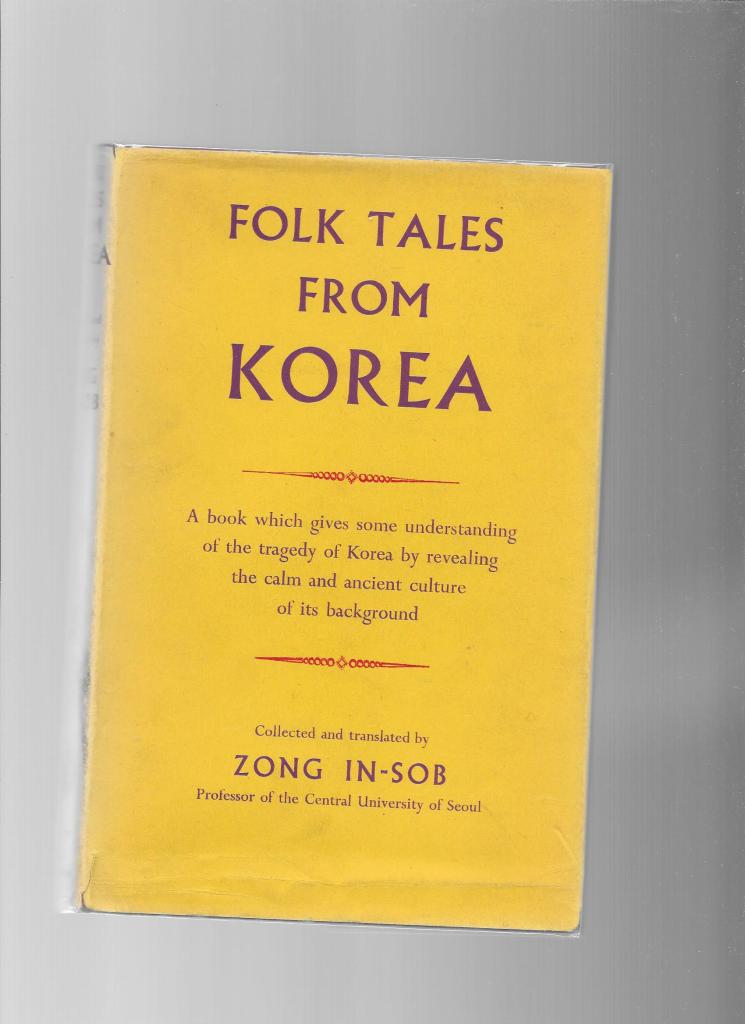

[i] Retold from Zong In-Sob, Folk Tales from Korea (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1952), no. 36, pp. 66-68, who apparently had the story from an earlier collection published in Seoul in 1925. Several other versions on the internet.

A mask by an unidentified Makonde artist of the mid-20th century QCC Art Gallery of the City University of New York, Smithsonian Magazine.

Once, they were thought to be. Then they were not. Now, it seems possible that many might be.

Recent genetic research into the origins of the Swahili people of East Africa strongly suggests that the ancient account of their kings, known as the Kilwa Chronicle, is substantially correct. In that narrative, the Swahili people of Africa are said to have originated in Persia (Iran) and began mixing with Africans one thousand or more years ago.[1]

Other research over the last decade or so has also provided support for the likelihood that traditional narratives, previously dismissed as fables, probably do record events that happened in deep time.

The frenzy of story collecting that accompanied the mercantile and colonial expansion of Europe from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth century led to the first attempts to understand the world’s massive body of folk and traditional narrative. Excited scholars proposed many theories of the origins and diffusion of these tales. Was it simply coincidence that the same stories, in one or another variation, appeared time and time again among cultures not known to have ever had any direct connection? How old were they? Could they be true?

The answer to the first question may be ‘as old as time’, at least human time.

Using the Gaia space telescope, astronomers studying the constellations and how they appear in various mythologies across the world have recently added further evidence for the antiquity of story. The star pattern known as the Pleiades was the object of mythmaking in many ancient cultures, many of which refer to seven stars that make it up. Today, we can only see six stars, but 100 000 years ago, seven stars would have been visible, strongly suggesting that the Australian Aboriginal Seven Sisters songline, the Greek story of the seven daughters of Atlas and similar storylines in African, Native American and Asian traditions had their origins in the way things were one hundred millennia ago.[2]

The answer to the second question is equally momentous.

Stories of a great flood appear so often in so many of the world’s narrative traditions that many have concluded there must have been some such event or events in antiquity. Noah and his Ark may be the most familiar to many, but there are an immense number of variations on the theme. Until recently, the trend has been to dismiss oral traditions of historical or pre-historic events as fantasy. But research linking scientific evidence with indigenous stories has brought about a more nuanced interpretation.[3] One topic which can now be linked to provable pre-historic events is the inundation of land. Twenty or more Australian Aboriginal stories of such events are thought to be around 10 000 years old.[4]

One of those traditions is that of the Narrinyeri (Ngarrindjeri and other spellings) people of Lake Alexandrina and the Lower Murray region of what is now South Australia. They recounted a tradition of their great ancestor, Nurundere (also Martummere) to German Lutheran missionary, Heinrich Meyer, in the 1840s. This version of the story, part of a longer sequence, tells how Nurundere came to create a passage between Kangaroo Island and the mainland by causing the sea to ‘flow’ and so punishing his two fleeing wives. [5] Kangaroo Island was separated from what is now the mainland of South Australia around seven thousand years ago.

In 2020, archaeologists working in north-western Australia discovered Aboriginal settlements beneath the sea near the Burrup Peninsula at Cape Brugieres. The drowning of these sites is thought to have occurred between 7000 to 8500 years ago.[6]

Using weather patterns and other evidence, researchers have discovered that Polynesian oral traditions of sunken lands can be correlated with geological events.[7] Subsequent research in Australia found evidence that Aboriginal stories of a great flood on the east coast of the continent reflect a verified rising of sea levels around 7000 years in the past.[8]

Related research suggests that indigenous traditions in both Australia and Brazil might carry memories of the megafauna who were extinct by 40 000 years ago.[9] Adrienne Mayor has looked closely at the connections between fossil remains and First American myths and legends and at the archaeological evidence for warrior women.[10] Other researchers have used DNA evidence to trace the migration of narrative motifs from South Siberia to North America around twelve thousand years ago.[11]

In 2020, a team of geologists suggested that the Gunditjmara story explaining the origins of the volcano they call Budj Bim might relate to an event that occurred in southeastern Australia around 37 000 years ago. They suggest that ‘If aspects of oral traditions pertaining to Budj Bim or its surrounding lava landforms reflect volcanic activity, this could be interpreted as evidence for these being some of the oldest oral traditions in existence’.[12]

The extensive amount of archaeological and palaeontological research currently underway in all parts of the world is revealing new evidence of human occupation, journeying and interacting.[13] In recent years some of these discoveries and interpretations of them have rewritten the history of humankind. Some important parts of that history are held in age old tales.

[2] Efrosyni Boutsikas, Stephen C. McCluskey and John Steele (eds), Advancing Cultural Astronomy: Studies in Honour of Clive Ruggles, Springer International Publishing, 2021.

[3] Timothy Burberry, Geomythology: How Common Stories Reflect Earth Events, Routledge, 2021.

[4] Patrick Nunn, The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World, Bloomsbury, London, 2018.

[5] Collected by Meyer and quoted in Rev George Taplin, The Native Tribes of South Australia, E S Wigg & Son, Adelaide, 1879, pp. 60-61.

[6] Benjamin J, O’Leary M, McDonald J, Wiseman C, McCarthy J, Beckett E, et al. (2020) ‘Aboriginal artefacts on the continental shelf reveal ancient drowned cultural landscapes in northwest Australia’. PLoS ONE 15(7): e0233912.

[7] Patrick D Nunn, Vanished Islands and Hidden Continents of the Pacific, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2009.

[8] Patrick D. Nunn & Nicholas J. Reid (2016) ‘Aboriginal Memories of Inundation of the Australian Coast Dating from More than 7000 Years Ago’, Australian Geographer, 47:1, 11-47, DOI: 10.1080/00049182.2015.1077539. See also Patrick Nunn, The Edge of Memory.

[9] Patrick D Nunn and Luiza Corral Martins de Oliviera Ponciano, ‘Of bunyips and other beasts: living memories of long-extinct creatures in art and stories’, The Conversation, April 15, 2019 at https://theconversation.com/of-bunyips-and-other-beasts-living-memories-of-long-extinct-creatures-in-art-and-stories-113031, accessed January 2020.

[10] Adrienne Mayor, Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press, 2005 and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press, 2014.

[11] Korotayev, Andrey. ‘Genes and Myths: Which Genes and Myths Did the Different Waves of the Peopling of Americas Bring to the New World.’ History & Mathematics (2017): n. pag. Print.

[12] Erin L. Matchan, David Phillips, Fred Jourdan, and Korien Oostingh, ‘Early human occupation of southeastern Australia: New insights from 40Ar/39Ar dating of young volcanoes’, Geology, Volume 48, Number 4, 1 April 2020 at

[13] Some further examples in Graham Seal, ‘Story Makes Us Human’, Gristly History, 11 March 2023, https://wordpress.com/post/gristlyhistory.blog/1094.

How should we be human?

After surviving, this must have been one of the first questions our earliest ancestors asked themselves. It might have been asked around the same time that they wondered where they had come from and how their part of the world originated. It seems likely that the stories they evolved to explain what we generally think of as ‘creation’ also included guidelines for living together and for coexisting with the animals, plants and natural phenomena of the planet.

This consciousness may have evolved around the same time as language and the ability to shape it into narratives that could be told by one to another – and another and another, in a multi-generational chain of tellings. When writing evolved, those stories, perhaps thousands of years old by then, could be written down. They were. The earliest written works we have are tales of unknowable forces, titanic beings and tectonic configurations of earth, sky, land and sea. They are also tales of interaction between gods, monsters, demigods, heroes and, eventually, everyday mortals.[1]

Creation stories were told probably by all peoples wherever they came together into communities to get on with the business of living and dying. As well as engaging with the unknowable cosmic conundrums plumbed by all origin myths and, later, by organised religions, people needed to develop ways of getting on and getting by. This meant figuring out what worked, what did not and agreeing on the rules for living together.

How should procreation be managed? The universal human problem of ensuring a degree of separation in the gene pool was worked out and encoded in stories.

What should be done with the aged? Despatched when they could no longer contribute to the tribe, clan, or supportive group in which they had lived out their lives? Or did they have something unique to provide to the group? Wisdom, perhaps?

What is fair, equitable? What is not? Who should decide, and how?

Evil? What did that consist of and how could it be avoided or otherwise managed?

The unknowable. In deep time, pretty well everything in the natural world and beyond – including death. And then what?

These, and other fundamentals, were dealt with through narratives – myths, legends, fables, ‘fairy’ tales, as we now term them. Not only were stories like these evolved, told, written and ultimately printed around the world, they tended to be remarkably similar to each other. Mystical beings made the world. Gods – or a god – ran the afterlife. Heroes brought fire, descended to the underworld, or slew monsters, mostly to the ultimate benefit of their people. A great flood drowned the earth. Evil spirits abounded. Devils and demons had to be outwitted. Animals, places and everything else had to be named and their characteristics accounted for. People did stupid things. People did wicked things. Sometimes they were held to account and received their just desserts. Often, whether saints or sinners, the protagonists of stories were transformed. Or not. Life not only had to be lived, it had to be storied.

These processes, at once banal and profound, have been going on in storytelling since as long as we know.[2] As well as their speech, people hold onto the tales carried within their language. Many of these are carried on the tongue rather than the page. But even where oral communication has been largely replaced by print and visual media, the same old tales continue to be told in books, films, digital games. [3]

How old are these stories? The answer to that question may be ‘as old as time’, at least human time.

Using the Gaia space telescope, astronomers studying the constellations and how they appear in various mythologies across the world have recently added further evidence for the antiquity of story. The star pattern known as the Pleiades was the object of mythmaking in many ancient cultures, many of which refer to seven stars that make it up. Today, we can only see six stars, but 100 000 years ago, seven stars would have been visible, strongly suggesting that the Australian Aboriginal Seven Sisters songline, the Greek story of the seven daughters of Atlas and similar storylines in African, Native American and Asian traditions had their origins one hundred millennia ago.[4]

Could these stories possibly be true? Do they somehow record historical, or even pre-historical, events?

The truth that western scholars sought, and mostly still do, is an objective reality based on verifiable evidence. That version is generally given in a linear sequence, originally through chronicles, later in histories, that present a more or less coherent narrative of events through time. But this is a very European notion. Elsewhere in the world, time is not streaming from past to present and into the future.

The Australian Aboriginal ‘Dreamtime’ (a western attempt to describe it), like many other indigenous mythologies and spiritualities, exists in an ‘always-ever’ form in which these neat chronological divisions do not exist. The past is here now and the future is held in the past, all of which could well be happening right now. And is. I have been told by Aboriginal people of evil night beings who lurk at a particular location. The traditional owners of what is now known as ‘Nyungar country’ in Western Australia, will not go near that place after dark.

Nor are stories of the past necessarily told through one voice or perspective. The people who migrated south through the tenth to thirteenth centuries into what is now Mexico evolved a culturally diplomatic form of storytelling that made space for the interpretations of different, previously warring groups who were now allied through intermarriage and common interest. When the stories of these people, who we know as ‘Aztecs’, were told, different speakers could stand up and tell their version of particular, usually traumatic, events.

In these tellings, chronology had little purchase as stories flowed between different periods, often in what western scholars perceived as confusing repetition and so, as evidence of degraded or incoherent and fragmentary forms of oral transmission. Modern scholarship has revealed that repetition was a necessary feature of Aztec historical storytelling. Their historical truth was a communal, consensual one, a composite of the various and often conflictual meanings of what had happened to them.[5]

Humankind’s body of story remains in obscure publications and vast archives around the world, many of which are not even catalogued, let alone fathomed.[6] These narrative treasures, known and still unknown, are the fundamental cultural heritage of humanity. To allow them to languish is to abandon the roots of our being and the lessons they contain for living and dying on planet earth. Confronting though it may be, this is the human condition.

Scientists also speculate that the very act of telling stories, of whatever kind, is itself essential to being human and surviving. Our brains process stories, whether ‘true’ or ‘fictional’, in ways that we find compelling as we try and understand the world and our place in it. Through telling and retelling ‘the metanarrative of human culture spins a half-real, half-fictional reality’.[7] Through this reality we achieve empathy, the state that allows us to share and comprehend the emotions of others as presented in stories that rehearse the primalities of existence. Fundamentally, these are benefits of cooperating with each other and understanding the consequences of not doing so.[8]

It seems that we instinctively respond to the deep meanings within these narratives. Anthropologist and author David Bowles recounts how his study of the Nahuatl indigenous Mexican myth brought him to a sense of self through an understanding that the Aztec, and all humanity, inhabit ‘a liminal space between creation and destruction, order and chaos’, understanding this fundamental equilibrium is ‘A gift bequeathed by the ancients to all of us, their biological and spiritual children alike.’[9] We can’t all learn to speak Nahuatl, but we can read the stories in translation and gain something of Bowles’s insight into self and the cosmos.

In keeping with the reworking of the past to present different views, traditional stories are frequently reinterpreted by fiction writers, especially from a feminist perspective. Psychologists and others involved in various forms of therapy are drawing on ancient traditions to help patients with a range of psychological, emotional and other problems.[10]

The meanings and purposes of the tales may differ between cultures, often in ways that outsiders cannot comprehend. But the global reverberation of the same narratives told across time and space resonates of common concerns beyond specific periods, places and storytellers. Story and storying confirm the essential oneness of human beings, now scientifically proven by genetics, with any two individuals differing by a negligible measure of DNA. [11]

* Referencing Deborah Bird Rose, Dingo Makes Us Human: Life and Land in an Australian Aboriginal Culture (1992)

[1] McCarthy, J., Sebo, E., & Firth, M. (2023). ‘Parallels for cetacean trap feeding and tread-water feeding in the historical record across two millennia’. Marine Mammal Science, 1– 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.13009.

[2] Smith, D., Schlaepfer, P., Major, K. et al. ‘Cooperation and the evolution of hunter-gatherer storytelling’. Nat Commun 8, 1853 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02036-8.

[3] Claudia Schwabe (ed), The Fairy Tale and Its Uses in Contemporary New Media and Popular Culture, Special Issue of Humanities 2016, 5, 81; doi:10.3390/h5040081, http://www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities, accessed June 2017.

[4] Efrosyni Boutsikas, Stephen C. McCluskey and John Steele (eds), Advancing Cultural Astronomy: Studies in Honour of Clive Ruggles, Springer International Publishing, 2021.

[5] Camilla Townsend, ‘How Aztecs Told History’, Aeon, https://aeon.co/essays/for-the-wanderers-who-became-the-aztecs-history-was-a-chorus-of-voices and Camilla Townsend, Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs, Oxford University Press, New York, 2019.

[6] A case in point is the discovery of a field collection of tales made in Germany at the time the Grimms were busy elsewhere, see Franz Xaver von Schonwerth (Author), Erika Eichenseer (Editor), Engelbert Suss (Illustrator), Maria Tatar (Translator), The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales, Penguin, 2015. Many of the stories are like those collected and/or anthologised by the Grimms, yet they are given without editing and are often darkly or perplexingly different to those that have become canonical through the unbalancing influence of the heavily edited tales of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

[7] Le Hunte, Bem & Golembiewski, ‘Stories have the power to save us: A neurological framework for the imperative to tell stories’, Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 5(2), January 2014.

[8] Singh, Manvir. “The Sympathetic Plot, Its Psychological Origins, and Implications for the Evolution of Fiction.” OSF Preprints, 23 June 2019. Web; Manvir Singh, ‘Orphans and Their Quests’, Aeon, https://aeon.co/essays/what-makes-the-sympathetic-plot-a-universal-story-type.

[9] David Bowles, ‘Learning Nahuatl, the Flower Song, and the Poetics of Life’, Aeon, https://psyche.co/ideas/learning-nahuatl-the-flower-song-and-the-poetics-of-life.

[10] The works of Carl Jung on ‘archetypes’ and of Joseph Campbell on the hero’s journey are the most influential. For other theories of heroic narrative and its significance see Robert A Segal (ed), In Quest of the Hero, Princeton University Press, 1990 for a survey of the main theories up to the 1990s.

[11] Gaia Vince, ‘Ancient Yet Cosmopolitan’, Aeon, https://aeon.co/essays/the-modern-human-mind-evolved-further-and-farther-back. The lack of genetic diversity in human populations also gives the lie to any pretence that Europeans are more intelligent, moral or more evolved than any other cultures.

The Conjuror, by Hieronymus Bosch and workshop, between 1496 and 1516. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the most basic, yet also the potentially most sophisticated gambling games is generally known as the shell game. The game was played in Europe from at least the fifteenth century and has been in England from at least the last half of the seventeenth century. By the eighteenth century the game was known as thimblerigging, under which name it was exported to America in the late eighteenth century. It was subsequently adapted by American grifters and provided the basic structure of large-scale cons like those featured in films such as The Sting and the more recent Oceans 11 and Oceans 12 movies.

A thimble was eighteenth century Cant for a watch, a watchmaker’s shop being a thimble-crib. Those who stole watches were known as thimble-getters or thimble-twisters. The latter word was also used to describe a thimble player, one who played the three shell game known as the thimble rig. At this time the game was usually played with thimbles and buttons, with peas and walnut shells coming into use a little later.

Whatever the exact implements involved, the shell game had the same basic features. Usually three thimbles were displayed on a board or table, together with a pea that was regularly covered and uncovered by one of the thimbles as the operator moved them around. The location of pea was, at first, easy to follow, inducing the player to bet. When a bet was laid, instead of leaving the pea beneath the thimble, the operator secreted the pea in his fingers and won the bet. There were many variations of surprising sophistication on this basic theme, but the shell game was basically a simple gambling diversion that, with some practice and nimble-fingers could be easily rigged. As it was generally illegal, the basic equipment was conveniently easy to hide or discard should any authorities take an undue interest in the proceedings.

By the mid-nineteenth century, thimblerigging was commonplace. In an 1862 publication, Henry Mayhew and John Binny[1] described people who lived by deceitful games of chance as being amongst the criminal classes of those ‘who live by getting what they want given to them’. These flatcatchers and charley pitchers ‘live by low gaming – as thimblerig-men.’ Flatcatchers were those who swindled flats, or ordinary people, a term that would continue to be used to describe the general public in American Carny talk. Charley pitchers were thimbleriggers who deceived country folk, or charleys, in the terminology of the time, also called, as they still are, yokels.

Mayhew and Binney also noted something of the deceptive character and magician-like skills of these coarse but effective swindlers. These swindlers were known as magsmen. Magging was a term generally used to cover the diversity of small-scale but effective cons perpetrated on yokels and other gullibles at fairs, shows, race-tracks, markets and wherever else people gathered to trade, gawp or enjoy themselves. The games, or swindles, included thimble-rigging, but also pitch and toss, skittles, the three card trick, the E.O. stand and the cogged dice used by charley pitchers. Victims were steered or lured into the carefully contrived web of the maggers, lulled into a false sense of security and good cheer, then ruthlessly rooked (since the sixteenth century) for all they were worth.

Well over half a century before then, if not earlier, the shell game migrated to America where it operated much as it had in England and Europe. Wherever crowds gathered, especially at festive or entertainment events, such as fairs, horseracing tracks and travelling shows, the thimbleriggers gulled the unwary into parting with their money. By the nineteenth century these operators became a common feature of road shows, usually being separate from the performers and other show workers but travelling with the troupe under a variety of nefarious income-splitting arrangements with the management. They became known as grifters in the early twentieth century and had an extensive language, or argot, of their own which reflected and supported the elaborate con that the shell game had by then become.

The main form of the game, as described by Maurer[2] from his fieldwork from the 1930s, involved the inside man or dink spieler who operated the shells, an outside man who encouraged the mark, or victim, and a number of ropers who found other likely marks in the crowd and steered them towards the game. The other essential member of the mob was a stick handler whose job was to hire a few usually young naïve men from the town where the show was playing. These gullible accomplices, or sticks, were used to keep the game warm while the thimbleriggers waited for genuine new players to be attracted or shepherded into the game. Also known as shills or boosters, the sticks, would, at the clandestine command of the stick-handler, excite the crowd, or tip, into the possibility of winning a lot of money very easily.

Also known as spreading the store, or framing the gaff, the three-shell board was now set up for the rooking routine. Relying on a well-rehearsed patter called spieling the nuts, some sleight-of-hand and surreptitious signals to his various accomplices, the inside man began the first of three, or possibly four, well-defined stages of the scam. This phase of the routine, known as the convincer, involved marking in the prat, placing him directly in front of the board to show him how the game worked. One of the shills then made a bet and won, strongly suggesting that the game was easy to win.

The runaround stage that follows is similar, except that the shill now bets and loses. This is done in such a way as to make the mark think that he can see how the pea is manipulated beneath the shells. On signals, or offices, and communications in argot or cross fire, from the inside man to the stick-handler, the shills are slipped money to place bets rapidly and warm up the crowd. At this point the outside man, making sure he is standing next to the mark, suggests to him that it looks pretty easy once you can see how it is done, so why not make a bet? The mark does – and loses. Meanwhile the sticks boost the betting action along. At this point the outside man reassures the mark that he needs only to keep a closer eye on the pea in order to win and pulls a large amount of money out of his pocket. The mark has another go and this time wins.

Now the countdown begins. The outside man bets a small note and loses, putting away his money and asking to see the shells being moved again. Claiming that he can now see which shell the pea is under, the outside man prepares to bet again, being sure to ask the mark to hold down the shell while he gets his money out again. This time the inside man says that if he thinks he is sure where the pea is, would he be prepared to bet all his cash? Confidently, the outside man throws all his money down and the inside man covers his bet with a matching amount. The mark is still holding down the shell and is now asked to turn it over.

Of course, the pea is there and the outside man has won a very large amount of money. He asks to try once again and offers to hold the shell for the mark if he wants to make another bet. At this point the stick handler distracts the inside man long enough for the outside man to quickly lift the shell far enough to show the mark where the pea is located. No chance of losing. The inside man immediately says to the mark that he will match his bet for all the cash he has. The mark bets his long dough, the shell is turned over but the pea is not there – the outside man has copped it while showing the mark the location of the pea, or giving him a flash peek. The mark is then considered whipped and leaves poorer but no wiser. There are a number of variations and additions for over-cautious marks, but the pea will never be where the mark thinks it should be whenever he or she bets their roll.

This scam was capable of fleecing hundreds and even thousands of dollars a day from the gullible and greedy. At the end of the day the shell mob retired to the privilege car, a special vehicle kept by the show’s management for grifters, often supplying alcohol and gambling opportunities. Here the takings were divided up. The management took 60%, from which they paid 10% to the patch, one employed by the show to fix the necessary arrangements with the local authorities. The inside and outside men got 20% apiece and the stick handler received wages. As one old shell game artist told Maurer, ‘They never pay out jack to a booster, just fill them full of lemonade and popcorn and sometimes promise them a lay with one of the showgirls, but that never happens …’.

[1] Mayhew, Henry & Binny, John, The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (The Great World of London), London, 1862.

[2] Maurer, David W, Language of the Underworld, collected and edited by A Futrell and C Wordell, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1981.

Recent research has turned up more fascinating facts and exposed a hoary myth about the last Thylacine, or ‘Tasmanian Tiger’. What the researchers had to say about their discovery of the skin of the last of these mythic beasts and the ‘bullsh..t’ that the animal was a male named ‘Benjamin’ is related at the link below. A small case study of how misinformation and myth arises and persists.

When transportation to the American colonies ceased after the War of Independence, British goals soon overflowed with prisoners. This situation soon created a new form of penal horror

To ease the pressure on prisons the government allowed old ships to be anchored in the River Thames (and at Portsmouth, Plymouth and elsewhere) to hold prisoners awaiting banishment across the seas. These ‘hulks’ were supposed to be a stopgap measure, but like many temporary arrangements they became permanent. Many prisoners would endure years aboard the rotting hulks, doing hard labour on the docks and in the naval arsenals, until they were finally transported.

The Dunkirk hulk moored at Plymouth was notorious even before the First Fleet set sail. Prisoners were sometimes without any clothing and in 1784 the abuse of the female convicts by the marine guards led to a ‘Code of Orders’ that were supposed to protect the women. Mary Bryant, later an almost successful escapee from Port Jackson, was held on the Dunkirk before sailing with the First Fleet. She became pregnant on the hulk.

Conditions aboard the Leviathan hulk at Portsmouth in the 1820s were better, but designed to strip convicts of whatever dignity they retained and subdue them into the system:

‘…this vessel was an ancient ’74 [1774] which, after a gallant career in carrying the flag of England over the wide oceans of the navigable world, had come at last to be used for the humiliating service of housing convicts awaiting transportation over those seas. She was stripped and denuded of all that makes for a ship’s vanity. Two masts remained to serve as clothes props, and on her deck stood a landward conceived shed which seemed to deride the shreds of dignity which even a hulk retains.’.

The prisoners were taken aboard and ‘paraded on the quarter-deck of the desecrated old hooker, mustered and received by the captain. Their prison irons were then removed and handed over to the jail authorities, who departed as the convicts were taken to the forecastle. There every man was forced to strip and take a thorough bath, after which each was handed out an outfit consisting of coarse grey jacket, waistcoat and trousers, a round-crowned, broad-brimmed felt hat, and a pair of heavily nailed shoes. The hulk’s barber then got to work shaving and cropping the polls of every mother’s son.’ Fettered and shaven prisoners were then marched below ‘where they were greeted with roars of ironic welcome from the convicts already incarcerated there’. The lower deck was a prison of wooden cells, each one holding between fifteen and twenty convicts.[i]

Edward Lilburn, a pipe-maker from Lincoln, described his experience of the Woolwich hulks around 1840:

‘I was led to think there was something dreadful in the punishment I had to undergo, but my heart sank within me on my arrival here, for almost the first thing I saw was a gang of my fellow unfortunates, chained together working like horses. I was completely horror-struck, but every hour serves now to increase my misery; I was taken to the Blacksmith and had my irons, the badge of infamy and degradation rivetted upon me, my name being registered and my person described in the books of the ship; I was taken to my berth, and here new sufferings presented themselves, as the great arrival of convicts had crowded the ship so much, that three of us have but one bed, and this the oldest prisoner claims as his own; our berth is so small, we have no room to lie at length, thus I passed a wretched, a half sleepless night, at the dawn of day we have a wretched breakfast of skilley, in which I cannot partake, and though suffering dreadfully from hunger I subsist wholly on my dinner, at present live on one meal a day!!’

Lilburn had the cheek to complain but was told that he was ‘brought here for punishment and that I must submit to my fate.’ He finished with a warning: ‘Whether I speak of my present situation in reference to daily labour, daily food, or the rigorous severity of the system under which I suffer, I can say, if there is a Hell on earth, it is a convict-ship. Let every inhabitant of the City and County of Lincoln know the Horrors of Transportation, that they may keep in the path of virtue, and happily avoid a life like mine of indescribable misery.’[ii]

After 1844 convicts were transported directly from the prisons where they were held rather than being sent first to the hulks. But the old ships still operated as gaols. By the time the journalists and social reformers Stephen Mayhew and John Binney visited the Thames hulks in the early 1860s, public outcry against the conditions and horrors of the hulks as described by Lilburn and others had already brought about reforms to the system, allegedly at least. Mayhew described conditions aboard the hospital ship Unité just a few years earlier in 1849:

‘… the great majority of the patients were infested with vermin; and their persons, in many instances, particularly their feet, begrimed with dirt. No regular supply of body-linen had been issued; so much so, that many men had been five weeks without a change; and all record had been lost of the time when the blankets had been washed; and the number of sheets was so insufficient, that the expedient had been resorted to of only a single sheet at a time, to save appearances. Neither towels nor combs were provided for the prisoners’ use, and the unwholesome odour from the imperfect and neglected state of the water-closets was almost insupportable. On the admission of new cases into the hospital, patients were directed to leave their beds and go into hammocks, and the new cases were turned into the vacated beds, without changing the sheets.’[iii]

Mayhew and Binney interviewed one of the warders who served under the previous ‘hulk regime’ who said that ‘he well remembers seeing the shirts of the prisoners, when hung out upon the rigging, so black with vermin that the linen positively appeared to have been sprinkled over with pepper…’. By the time this survey was conducted there was regular medical treatment available, a lending library, education for the man who could not read or barely so. The food provided had also improved dramatically, at least according to the regulations:

‘We now followed the chief warder below, to see the men at breakfast. “Are the messes all right ?” he called out as he reached the wards.

“Keep silence there! keep silence!” shouted the officer on duty.

The men were all ranged at their tables with a tin can full of cocoa before them, and a piece of dry bread beside them, the messmen having just poured out the cocoa from the huge tin vessel in which he received it from the cooks; and the men then proceed to eat their breakfast in silence, the munching of the dry bread by the hundreds of jaws being the only sound heard.’

Each prisoner received a breakfast of twelve ounces of bread and a pint of cocoa. For dinner they were allowed six ounces of meat, a pound of potatoes and nine ounces of bread, for supper a pint of gruel with six ounces of bread. Wednesdays, Mondays, and Fridays were ‘Soup Days’, when the dinner was a pint of soup, five ounces of meat, a pound of potatoes, and nine ounces of bread.

For punishment, the luckless convict was reduced to a pound of bread and water each day. Those on the sick list were fed a pint of gruel and nine ounces of bread for breakfast, dinner, and supper. But an enhanced diet was given to the very sick, as the master of the hospital told the journalists:

‘The man so bad, up-stairs, has 2 eggs, 2 pints of arrowroot and milk, 12 ounces of bread, 1 ounce of butter, 6 ounces of wine, 1 ounce of brandy, 2 oranges, and a sago pudding daily. Another man here is on half a sheep’s head, 1 pint of arrowroot and milk, 4 ounces of bread, 1 ounce of butter, 1 pint extra of tea, and 2 ounces of wine daily.’

The trades and occupations of convicts in the 1850s included carpenters, blacksmiths, painters, sawyers, coopers, rope makers, bookbinders, shoemakers, tailors, washers and cooks, even the occasional doctor. Convicts received ‘gratuities’ for the quality of their work and general conduct. They wore badges which indicated their duration of sentence, period in the hulks and levels of good or bad behavior, updated monthly, the details entered into the ‘character book’ of each hulk.

Mayhew also described the work performed by those whose labor was now at the control of the state.

‘The work of the hulk convicts ‘is chiefly labourers’ work, such as loading and unloading vessels, moving timber and other materials, and stores, cleaning out ships, &c., at the dockyard; whilst at the royal arsenal the prisoners are employed at jobs of a similar description, with the addition of cleaning guns and shot, and excavating ground for the engineer department.’

Mayhew saw the working parties in the dockyards:

‘… only the strongest men are selected for the coal-gang, invalids being put to stone-breaking. In the dockyard there are still military sentries attached to each gang of prisoners. We glanced at the parties working, amid the confusion of the dockyard, carrying coals, near the gigantic ribs of a skeleton ship, stacking timber, or drawing carts, like beasts of burden. Now we came upon a labouring party, near a freshly pitched gun-boat, deserted by the free labourers, who had struck for wages, and saw the well-known prison brown of the men carrying timber from the saw-mills. Here the officer called – as at the arsenal – “All right, sir!” Then there were parties testing chain cables, amid the most deafening hammering. It is hard, very hard, labour the men are performing.’

Most closely regulated of all was convict time. From the moment of waking – 5.30 in summer, half an hour later in winter – the prisoners of the hulks ate, worked, washed and prayed to a strict timetable. All were in their beds or hammocks at 9pm.

This strictly regulated world of servitude, obedience and hard labour was an essential element of the larger penal transportation system of the British empire. It lasted for centuries

Adapted from Great Convict Stories from

allenandunwin.com/browse/book/Graham-Seal-Great-Convict-Stories-9781760527488/

[i] James Tucker, (‘Giacomo Rosenberg’), The Adventures of Ralph Rashleigh: A Penal Exile in Australia, 1825-1844.First published in 1929, though thought to have been written in the 1840s.

[ii] A Complete Exposure of the Convict System. Horrors, Hardships, and Severities, Including an Account of the Dreadful Sufferings of the Unhappy Captives. Containing an Extract from a Letter from the Hulks at Woolwich, written by Edward Lilburn, Pipe-Maker, late of Lincoln, from a broadside in the Mitchell Library (Ferguson 3238).

[iii] Henry Mayhew, John Binney and Benno Loewy, The criminal prisons of London, and scenes of prison life, London, Griffin Bohn, 1862. p. 200.

Funny, curious and downright astonishing stories from across a big country

Wherever you go in Australia, you’ll stumble across traces of ancient settlement, remnants of exploration, yarns from the roaring days of gold and bushranging, unexplained events and a never-ending cast of eccentric characters. Read all about it here

The Way to Kukuanaland, from King Solomon’s Mines by H. Rider Haggard. Eça de Queiroz

A sturdy figure clothed in leather stumbles through the mostly unknown wilderness of southern Africa’s Transvaal in 1865.A revolver, compass, sextant, hunting knife and tin bowl dangle from the man’s belt. He cradles a double-barrelled rifle in his hands and a blanket slung over his shoulder – poorly equipment for his dangerous quest.

Since boyhood, Karl Mauch had been fascinated with faraway places and lost kingdoms. He spent his youth studying and acquiring the skills needed to pursue a life of adventurous archaeology – languages, mapping, minerology, history. While still young, Mauch decided he was ready to find the lost city of Ophir.

He arrives by ship in South Africa in 1865. Supporting himself as best he can he explores and maps the Transvaal. In 1866, accompanied by the English elephant hunter ,Henry Hartley, Mauch visits and maps the region between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers. He also hears many tales from Hartley about ancient gold mines and lost cities. The following year, now travelling alone, the German explorer discovers a number of old gold smelting works and fields in Mashonaland. He also discovers rich gold deposits near the Botswana-Zimbabwe border.

In 1868, still following his dreams, Mauch is kidnapped by the Matabele and is lucky to survive. He makes a brief trip in early 1869 and finds indications of gold along a tributary of the Zambezi. He has no further funds until 1870 when he travels in a leaky boat along the Vaal River in another epic journey of hardship and survival. Again, the following year he sets out to find an ancient city he believes lies beyond the Limpopo River. He is robbed by natives and left with nothing. Starving and on the verge of suicide he is rescued by another group of Africans and comes into contact with the enigmatic German American hunter, Adam Render(s).

After an adventurous life in the bush and as a soldier, Renders had deserted his family a few years earlier and was living with the Shona people. He takes Mauch in and guides him to some ruins he stumbled across in 1867. After examining the broken stones and talking with the local population, Mauch concludes that he has found the mysterious golden city of Ophir and so, King Solomon’s mines.

The city or region of Ophir is mentioned in the Bible and other early religious texts as a source of great wealth. According to the story, Ophir (various spellings) was the foundation of King Solomon’s riches. He was surrounded by an excess of gold and dispensed justice and wisdom to his people. Every three years Solomon received a shipment of silver, ivory, sandalwood, jewels and gold from Ophir, along with apes and peacocks. All these things were greatly prized in the ancient world and are the origins of what would become the legend of King Solomon’s mines.

Of course, no one knew where the mines were located. Until the early sixteenth century when a member of Vasco de Gama’s 1502 voyage to India, Tome Lopes, claimed to have found them. Lopes saw the astonishing ruins of Great Zimbabwe and decided that this must have been the region called Ophir. He wrote a report of his adventures and ideas that circulated widely in Portugal and elsewhere, popularising the idea that Ophir and therefore its wealthy mines must be in southern Africa rather than the middle east.

The rush was on. Expeditions of hopeful treasure hunters flocked to the unknown continent. Maps appeared showing the alleged location of the treasure trove. The legend grew. By the time Karl Mauch was seduced by the golden mystery Ophir and King Solomon’s mines were perhaps the world’s best-known lost treasure legend.

After his hard-won find, Mauch returned to Germany expecting, with some justification, to be hailed as a great adventurer, mapmaker and archaeologist. He was not. Without formal qualifications he was unable to gain an academic or museum post. He briefly took part in an expedition to Central America in 1874 but was only able to find work back in Germany as a foreman in a cement factory. His health failed and just before his thirty-eighth birthday he somehow managed to fall from his first-floor window while sleeping. He died a few days later.[i] The legend claimed yet another hopeful soul.[ii]

Karl Mauch had not found the fabled city of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, nor the King’s gold. But he had found a much greater treasure. The city of Great Zimbabwe was erected during the 11th century and grew to be an important trading hub in the 13th century. By the time the Portuguese arrived 300 years later, the city had been abandoned. No one knows why. Another enduring mystery in its own right.

Solomon’s mines and Ophir remained in the mists of myth but the existence of Great Zimbabwe’s ancient architecture, together with the real riches being extracted from southern Africa, fuelled belief in the mines. The legend received its greatest boost with the publication of ‘the most amazing book ever written’ in 1885. H Rider Haggard’s boys’ own adventure titled, of course, King Solomon’s Mines.

Haggard was an old Africa hand. He was familiar with the local traditions of lost treasures and Mauch’s quest, as well as the Biblical story of Ophir. Perhaps the greatest best seller of the nineteenth century, and still in print, Haggard’s romance and its many spinoffs in popular literature and movies have kept the notion of King Solomon’s mines in the public consciousness ever since. The fabled mines are regularly ‘found’ though the claims are just as regularly debunked.[iii]

But, of course, the quest continues.

[i] C Plug, ‘Mauch, Mr Karl’ in S2A3 Biographical Database of Southern African Science, http://www.s2a3.org.za/bio/Biograph_final.php?serial=1867, accessed March 2016.

[ii] ‘Karl Mauch’ in National Geographic Deutschland, http://www.nationalgeographic.de/reportagen/entdecker/karl-mauch, accessed March 2016; F O Bernhard (ed and trans), Karl Mauch: African Explorer, C Struik, Capetown, 1971.

[iii] James D Muhly ‘Solomon the Copper King: A Twentieth Century Myth’ in Expedition, vol 29, no 2, 1987, pp. 38-47.