Beggars were a large and troublesome presence throughout Europe during and after the middle ages. The tolerance, even encouragement, of the church for mendicancy as an expression of piety ensured that roads were thronged with men, women and children bent on extracting money from better-off passers-by. Henry VIII’s seizing of the monasteries and the increasing enclosure of previously public lands inflamed the problem, as did the arrival of large numbers of impoverished Irish. By the reign of Elizabeth 1 begging might be punished by maiming and even death. As the problem was basically a consequence of economic forces, these harsh measures were ineffective, as were the Poor Laws and the parish relief system that were subsequently introduced.

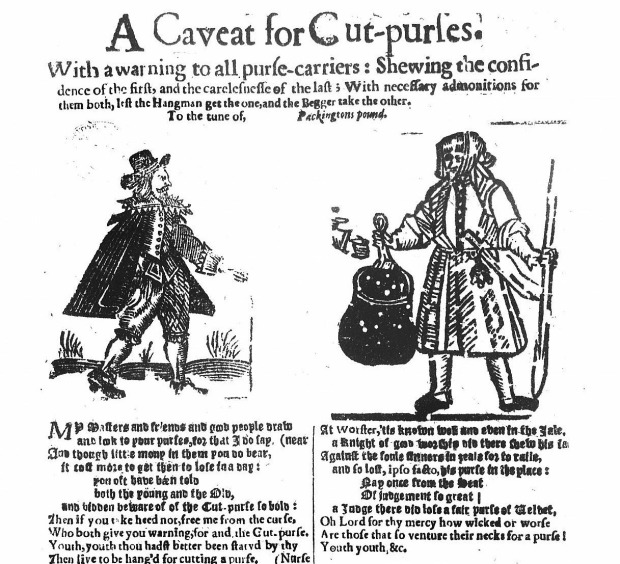

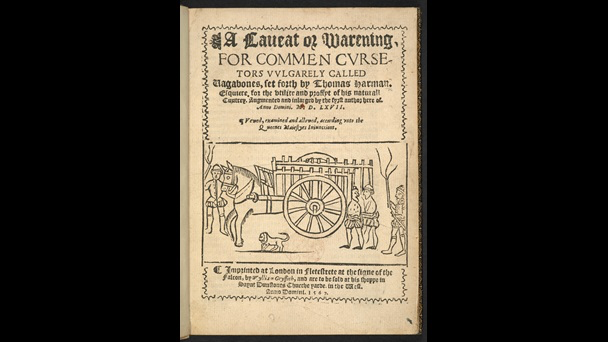

The beggar remained a familiar, ever-inventive type often execrated in the cautionary writings of sixteenth and seventeenth-century authors like Dekker, Harman and other observers of the swarming ‘canting crews’. Such was the diversity of begging ploys that many felt it necessary to categorise and describe them for the benefit and protection of their fellow respectable citizens. In the earliest of what would become a number of beggar books, Fraternity of Vagabonds (1561) by John Awdeley, nineteen different types of vagabonds are named. These include a jackman, one who forges documents, or gibes with false seals known as jarks. In 1566 Thomas Harman described dommerars who:

‘… wyl never speake, unless they have extreme punishment, but wyll gape, and with a marvellous force wyll hold downe their toungs doubled, groning for your charyty, and holding up their handes full pitiously, so that with their deepe dissimulation they get very much.’

A later variation was for the dommerar to produce a piece of paper on which was written a note to the effect that his tongue had been cut out during a period of Turkish slavery because he had refused to convert to Islam.

Names of different kinds of beggars and beggaries across the centuries may vary, though their dodges were much the same. The early seventeenth century mason’s maund referred to a false injury above the elbow that made the arm appear broken as if by a fall from a builder’s scaffolding. Cadging was an eighteenth-century term for begging, also used to describe the lowest form of thief. It had numerous extensions, such as cadging ken, a public house frequented by cadgers. A cadger’s cove was a lodging house for beggars and the cadging-line, was the begging business. Durrynacking or durykin was to beg by telling fortunes in the early nineteenth century, usually practiced by women.

Beggars were also celebrated in songs that at once romanticised their lifestyle, revealed their tricks and some of their secret language. One very popular song of this type has its origins in Richard Broome’s play The Jovial Crew, originally produced in 1641. Although this song was probably added to it in the 1680s revival version, it preserves the use of pelf, meaning booty, which dates from at least the last part of the previous century. Among other things, the song highlights the apprenticeship system through which generations of beggars learned the trade, still operating in the nineteenth century in Britain and also among American hoboes until at least the early twentieth century:

There was a jovial beggar,

He had a wooden leg,

Lame from his cradle,

And forced for to beg.

And a begging we will go, we’ll go, we’ll go;

And a begging we will go!

A bag for his oatmeal,

Another for his salt;

And a pair of crutches,

To show that he can halt (limp).

And a begging, &c..

A bag for his wheat,

Another for his rye;

A little bottle by his side,

To drink when he’s a-dry.

And a begging, &c.

Seven years I begged

For my old Master Wild,

He taught me to beg

When I was but a child.

And a begging, &c.

I begged for my master,

And got him store of pelf;

But now, Jove be praised!

I’m begging for myself.

And a begging, &c.

In a hollow tree

I live, and pay no rent;

Providence provides for me,

And I am well content.

And a begging, &c.

Of all the occupations,

A beggar’s life’s the best;

For whene’er he’s weary,

He’ll lay him down and rest.

And a begging, &c.

I fear no plots against me,

I live in open cell;

Then who would be a king

When beggars live so well?

And a begging we will go, we’ll go, we’ll go;

And a begging we will go!

There were many other street ballads and stage songs on the theme of beggary, including ‘The Blind Beggar’s Daughter of Bethnal Green’, ‘Mad Tom of Bedlam’ and a Scots song from the late nineteenth century written by a hawker named Besom Jimmy. Scotland was particularly plagued by beggars and this song celebrates the open road and lifestyle of the tramp:

I’m happy in the summer time beneath the bright blue sky,

Nae thinkin’ in the mornin’ at nicht whaur I’ve tae lie,

Barns or buyres or anywhere or oot among the hay,

And if the weather does permit I’m happy every day.

Things were not much better by the time Henry Mayhew and others began investigating the lives of the London poor. Many tricks of the gegor’s trade had changed little over the centuries, though there were a few new dodges, such as smearing a limb with soap and adding vinegar to produce a realistic suppurating sore in the hope of eliciting the sympathies and the cash of the unwary.

One popular technique was the wounded war veteran, a variation on the merchant lay or the Royal Navy lay in which beggars impersonated ex-naval men, known generally as turnpike sailors. The wounded veteran described by Mayhew was:

a perfect impostor, who being endowed, either by accident or art, with a broken limb or damaged feature, puts on an old military coat, as he would assume the dress of a frozen-out gardener, distressed dock-yard labourer, burnt-out tradesman, or scalded mechanic. He is imitative, and in his time plays many parts. He “gets up” his costume with the same attention to detail as the turnpike sailor. In crowded busy streets he “stands pad,” that is, with a written statement of his hard case slung round his neck, like a label round a decanter. His bearing is most military; he keeps his neck straight, his chin in, and his thumbs to the outside seams of his trousers; he is stiff as an embalmed preparation, for which, but for the motion of his eyes, you might mistake him. In quiet streets and in the country he discards his “pad” and begs “on the blob,” that is, he “patters” to the passers-by, and invites their sympathy by word of mouth. He is an ingenious and fertile liar, and seizes occasions such as the late war in the Crimea and the mutiny in India as good distant grounds on which to build his fictions.

This beggar was unmasked as a fraud and asked to tell his story, recorded with the slang of the period and the calling intact:

I have been a beggar all my life, and begged in all-sorts o’ ways and all sorts o’ lays. I don‘t mean to say that if I see anything laying about handy that I don‘t mouch it (ie.steal it). Once a gentleman took me into his house as his servant. He was a very kind man; I had a good place, swell clothes, and beef and beer as much as I liked; but I couldn‘t stand the life, and I run away.

The loss o’ my arm, sir, was the best thing as ever happen‘d to me: it‘s been a living to me; I turn out with it on all sorts o’ lays, and it‘s as good as a pension. I lost it poaching; my mate‘s gun went off by accident, and the shot went into my arm, I neglected it, and at last was obliged to go to a orspital and have it off. The surgeon as amputated it said that a little longer and it would ha’ mortified.

The Crimea’s been a good dodge to a many, but it‘s getting stale; all dodges are getting stale; square coves (i e.honest folks) are so wide awake.

The unmasker of the beggar then asks him: ‘Don‘t you think you would have found it more profitable, had you taken to labour or some honester calling than your present one?’ The beggar replied: ‘Well, sir, p‘raps I might, but going on the square is so dreadfully confining’.

A powerful reason for this man’s preference for a life of beggary rather than employment was that beggars made a great deal more money than they might earn in gainful employment and enjoyed a much more lavish and roistering lifestyle. In 1816 it was reported that two houses in the notorious area of St Giles’s were home to between 200 and 300 beggars who averaged three to five shillings takings each day. It was said that ‘They had grand suppers at midnight, and drank and sang songs until day-break.’ A little earlier, a Negro beggar was reputed to have retired back to the West Indies with a substantial fortune of 1500 pounds earned from acting out roles in the street.

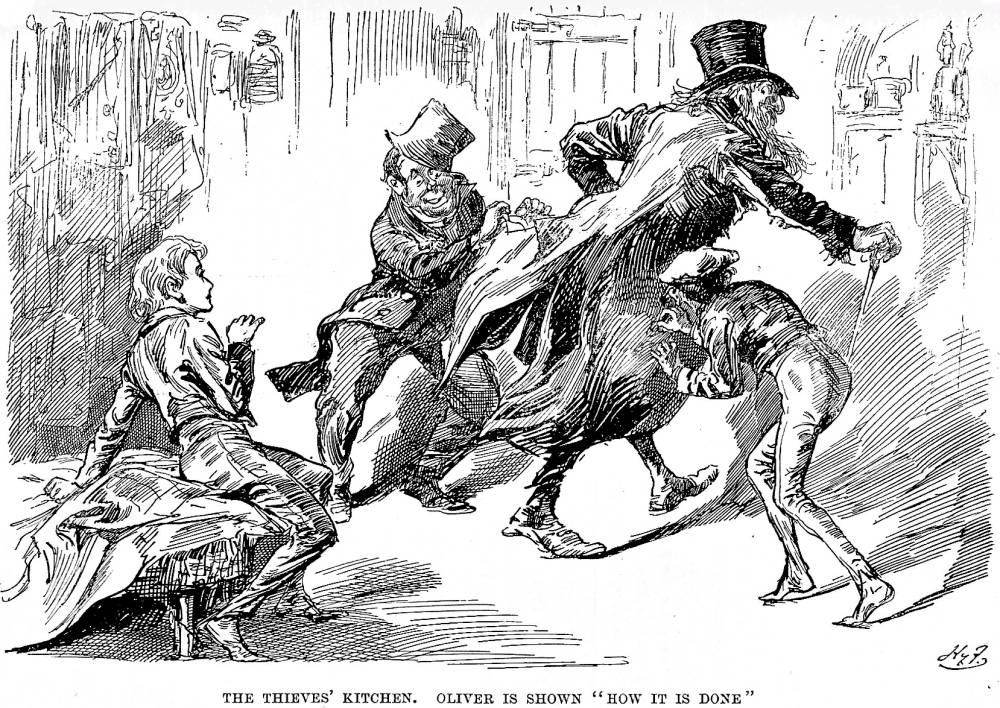

And how many there were. Mayhew describes dozens of different ways to separate the gullible and better-off from their pennies, perhaps even their pounds. There were sophisticated schemes involving begging letters of commendation, apparently endorsed or even written by nobles or other highly-placed and well-known persons of influence. In reality they were provided for a fee by screevers, usually comedown hacksand educated but dissolute wastrels not fussy how they earned a crust. Some lays were perpetrated mostly by women, involving children provided at a fee by establishments operating for just this purpose. And there were the maimed, the almost undressed who practiced the scaldrum dodge, the starving, the addled, the infirm and the displaced among many other forms of deception designed to wring hearts and purses. Broken-down tradesmen, scalded mechanics, decayed gentlemen, distressed scholars and clean families apparently down on their luck. It was an underworld industry on a grand scale that provided thousands, even tens of thousands with a living, if not a profit. Many of the poor worked their way through and up from beggary to something better, perhaps becoming a coster, as did at least one boy tracked over a ten-year period from street urchin to barrow boy.

In America a major form of beggary was associated with the down and out and the skid rows or skid roads of many cities and towns. While hoboes and many tramps may have prided themselves on their ability to support themselves by odd jobs and casual labour, other itinerants depended on the hand-out and various forms of mooching or being on the bum, almost as varied and elaborate as those practiced in England. There was an elaborate language evolved to describe the art of panhandling, also known as throwing your feet. To connect, or make a touch was the object of all panhandling, increasing the likelihood of the mark coming across. An eye doctor was someone skilled at this technique. A ghost story was a yarn told by a panhandler to gain sympathy and a handout, sometimes called a slob sister or a tear baby.

REFERENCES:

Awdeley, John, Fraternity of Vacabondes, 1575.

Beier, A.L, ‘Vagrants and the Social Order in Elizabethan England,’ Past and PresentLXIV (Aug. 1974).

Chesney, K., The Victorian Underworld, Temple Smith, London, 1970.

Dekker, Thomas, Lanthorne and Candle-light, London, 1609.

Hancock, I., ‘The Cryptolectal Speech of the American Roads: Traveller Cant and American Angloromani’, American Speech 61 (3), 1986, 206-220.

Harman, Thomas, Caveat or Warning, for Common Cursetors Vulgarly Called Vagabondes, or Notable Discovery of Coosenage, London, 1566, 1591.

Matsell, G., Vocabulum, or, The Rogue’s Lexicon, compiled from the most authentic sources, New York, 1859.

Maurer, David W, Language of the Underworld, collected and edited by A Futrell and C Wordell, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1981.

Mayhew, Henry & Binny, John The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (The Great World of London), London, 1862.

Mayhew, Henry, London Labour and the London Poor, 4 vols, London, 1851.

Sorenson, J., ‘Vulgar Tongues: Canting Dictionaries and the Language of the People in Eighteenth Century Britain’, Eighteenth Century Studies37.3, 2004.