Renowned Australian folk musician and singer Dave De Hugard has been singing and researching ‘Waltzing Matilda’, in one version or another, for many years. He has now released the fruits of his labours – a different angle on the origins of the famous song and a compelling new composition based on the original.

Listen to Dave sing his new song, ‘Waltzing Matilda: The Real Swagman’s Story’ here. (scroll to bottom of page)

Coincidentally, Dave also has a couple of new album releases out and available here

Untangling Matilda: A clarification of the origin of the original lyrics of Banjo Paterson’s ‘Waltzing Matilda’

In 1895 as a guest at Dagworth, the Macpherson sheep station, Banjo Paterson, inspired by a tune Christina Macpherson was playing, said to Christina that he thought he could put some words to it. He then and there created in a few lines of verse, the image of a happy swagman, singing as he boiled up his billy by a billabong, ‘Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?’

This in time would become the first verse of the ‘Waltzing Matilda’ that many of us know. Other verses would follow later, but they would take a decidedly different turn. In this paper I will be looking closely at events and incidents that may have played a significant part in inspiring those later verses. But before we do that, there are some important things we need to know.

First and foremost we need to know that there really was a swagman who drowned at a billabong known as the Combo waterhole. This happened in April 1893, two years before Banjo Paterson arrived at Dagworth. We don’t know who the swagman was but we do know that he had knocked off one of Bob Macpherson’s sheep. This was during the seriously troubled times of the shearer’s strike. At that time, a Constable Pat Duffy and a tracker were looking for a Dagworth stockman who had killed an aboriginal youth, for not looking after the horses properly; and it just so happened they headed towards the Combo waterhole where the swagman was camped. The swagman spotted them and decided to make himself scarce. He tried to get across the billabong but he drowned in the attempt.

That’s one thing we need to know. But we also need to know that Banjo Paterson was aware of this event. The Combo waterhole had been a picnic spot from time to time for the local graziers. And it was at a picnic at that Combo waterhole that Banjo heard from Bob Macpherson, not only the story of the drowned swagman, but also Bob Macpherson’s belief that the billabong was haunted by the swagman’s ghost. This information is contained in the 2nd edition of Sydney May’s ‘The Story of Waltzing Matilda’ (1955). It comes from a Jane Black, a friend of the Macphersons. Jane Black tells us that on a visit to the MacPhersons, she got a retelling from Bob Macpherson of the events that happened during the Paterson visit. This included confirmation from Bob Macpherson that Banjo Paterson had been a guest at a Combo waterhole picnic; and that during that picnic, the story of the drowned swagman and the swagman’s ghost had been told. She tells us also, that she was so impressed with Bob’s story of the drowned swagman and the ghost that haunted the billabong, that ‘we deviated a little next day on our way to Kynuna to get a good view of the magic waterhole’.

With this information under our belt, we can now look at the rest of the verses that Paterson put together to complete his waltzing Matilda story. And what we find is not at all a straight retelling of the story that he had heard from Bob Macpherson. The main ingredients are there – the police, the jumbuck, the drowned swagman and the ghost – but the story has changed completely. Not only does Paterson have the swagman caught and interrogated by his captors but he then has the swagman jump into the billabong and drown himself. He keeps Bob Macpherson’s ghost, but it now sings through the billabong, with a very much less promising, ‘Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me’.

And there is another change as well, and a particularly significant one. It is significant because it relates directly to what I believe Paterson’s original ‘Waltzing Matilda’ was all about. What he did was to remove the original police involved in Bob Macpherson’s account of the drowned swagman. And in their place he put a squatter on a thorough-bred with three policemen in tow. And this wasn’t just any squatter. This squatter was Bob Macpherson. And we know this, because in September 1894, the year before Paterson arrived at Dagworth, a band of striking shearers had burnt down the Macpherson wool shed with a 140 or so sheep inside. Many shots were fired during the night as well. And the next day, to his credit, Bob Macpherson rode out to the shearer’s camp with three policemen to confront the striking shearers. That is all understood and accepted. But what we really want to know is, what is Bob Macpherson doing, now popping up in the earlier drowned swagman story? There is an answer to this, but we first need to go back to the shearer’s strike.

One of the consequences of the strike was that there had been a major breakdown in the usual amicable relations between swagmen on the track and the homestead. Now, instead of calling into the homestead for the usual rations of sugar tea and flour, swagmen would just knock off a sheep in the paddock without a second thought; and this was still happening when Paterson was at Dagworth.

Bob Macpherson’s brother Gideon tells us for instance in some detail in the 2nd edition of Sydney May’s ‘The Story of Waltzing Matilda’ (1955), that Banjo & Bob Macpherson were out riding one day and they came across one of these sheep. It had been recently killed, the best bits taken and the rest just left to go to waste. Gideon then tells us that the completed ‘Waltzing Matilda’ followed soon after.

Christina Macpherson refers also to the same event, but she is more specific. Her reference is in an unsent letter (National Library of Australia) she wrote to Thomas Wood, the author of ‘Cobbers’. ‘Cobbers’ was a book about Australia and in it, Wood had included the words and music of ‘Waltzing Matilda’.

Christina says in her letter to Wood, that she is writing because she thought ‘it might interest you to hear how ‘Banjo’ Paterson came to write it’. She goes on to say that swagmen had been ‘helping themselves without asking’ and that Bob and Banjo Paterson had come across the remains of one of these sheep. She then says, and I quote, ‘Mr Paterson made use of the incident’. Christina doesn’t give us any more information, but that doesn’t really matter, because I believe we already have before us, all we really need to know.

The incident Christina is refering to here, is about Bob Macpherson, yet again, coming across another of his sheep that has been killed, the best bits taken, and the rest just left to go to waste. And it happened on this occasion that Bob Macpherson’s riding companion was Banjo Paterson – and Banjo, we know from his writings, had a good sense of humour. As such, my understanding of the incident Christina has just referred to, to put it quite simply, is that the occasion provided Banjo with an opportunity to have a bit of fun – and to cheer Bob Macpherson up in the process. It also just so happened that Banjo had at hand, still fresh in his memory, Bob’s earlier account of the drowned swagman at the Combo waterhole.

And it wouldn’t have taken Paterson long at all to put together some verses that poetically at least, would finally ‘turn the tables’ on the miscreants who had been knocking off Bob’s sheep! All he had to do was to have Bob Macpherson appear once again as that squatter on the thorough-bred with the three policemen in tow, and the job would be done! And that’s just what he did:

Down came the squatter a-riding his thorough-bred;

Down came policemen – one, two, three.

‘Whose is the jumbuck you’ve got in the tucker-bag?

You’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me!

And this squatter that has now found its way into the Matilda story, has of course nothing whatsoever to do with an event the previous September, when Bob Macpherson did actually ride out with three policemen to confront the shearers who had burnt down his wool shed. And similarly, nor does this Matilda squatter have anything whatsoever to do with Samuel Hoffmeister, the probable suicide that Bob Macpherson and the police came across on that same occasion.

I also think it very likely indeed that all of the Macphersons would all have understood exactly what Banjo Paterson had written and why – and that what he had written, furthermore, would also very likely, have provided them all with no small amount of amusement:

”So take note any more of you swagmen who think you can knock off Bob’s sheep and think you can get away with it!’

And that’s about it. And it was in that form that the song took off and rapidly became very popular. The verse about the swagman jumping in the waterhole and drowning himself, wouldn’t have appealed to everyone and it probably wouldn’t have been long before more preferable options for some, began to find their way into the song.

In closing, I’ll just say that it does need to be known that as ‘Waltzing Matilda’ was becoming more and more popular, the real story of the very real swagman who actually had been camped at that Combo waterhole, was already well on the way to becoming almost entirely forgotten. And I for one, believe that that story, is way, long overdue for a retelling!

(c) Dave de Hugard, Castlemaine January 2026

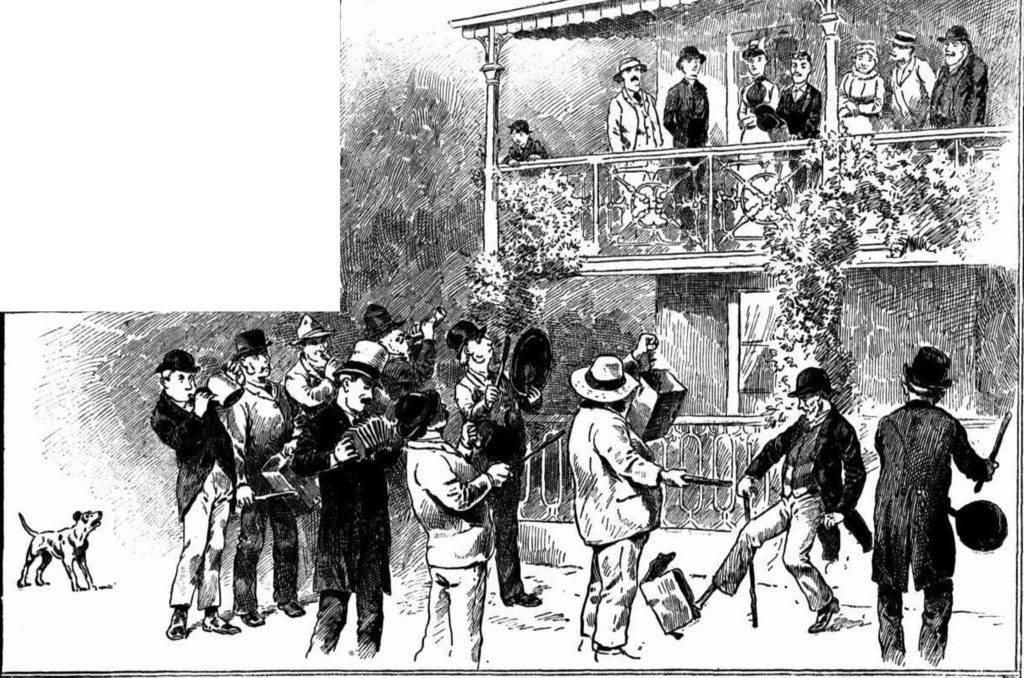

Bob Macpherson, 3rd from right, posing with the three policemen he rode out with in September 1894 to the striking shearer’s camp after they burnt down his woolshed.