What do ‘Waltzing Matilda and the ‘Aeroplane Jelly’ song have in common? They are both advertising jingles.

Most Australians know both songs, but few know that ‘Banjo’ Paterson’s poem, set to music by Christina Macpherson, was barely heard of before being used as an advertisement for ‘Billy Tea’ early in the 20th century. The musical come-on has been with us ever since.

While Chesty Bond, the Arnotts’ parrot and the swaggy facing out the ‘roo on the Billy Tea packet are well-known visual icons of national identity it is the catchy musical icons of Australian commercial culture that we can’t get out of our collective mind. The immortal melodies and deathless lyrics associated with ‘Mortein’, ‘Vegemite’, ‘Milo’, ‘Mr Sheen’ and, flying highest of all, ‘Aeroplane Jelly’ are our catchiest carols of consumerism. They have called us to corner shop and supermarket for generations. They are household brand names and elements of that shared soundscape that is as much a part of the Australian way of life as the bush, the beach and the Holden car. We may not know all the words but when we hear ‘The Aeroplane Jelly Song’ or ‘Happy Little Vegemites’ we immediately think of the products they purvey.

One of the most famous Australian products is a sticky black substance made from the leftovers of beer brewing. Long-owned by the American food giant, Kraft, Vegemite has for almost as long been widely acknowledged as the essential Australian foodstuff. Who has not been a ‘happy little Vegemite’, a phrase so powerful that it has entered our folk speech as a term for contentment?

We’re happy little Vegemites, as happy as can be

We all enjoy our Vegemite for breakfast, lunch and tea.

Mummy says we’re growing stronger every single day

Because we love our Vegemite, We all enjoy our Vegemite,

It puts a rose in every cheek.

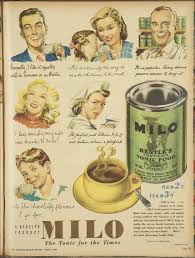

A simpler but no less effective musical come-on for a foodstuff was the jingle for the egg, malt, milk and almost everything else beverage marketed as ‘Milo’. While the advertisers of Milo did not claim to put ‘a rose in every cheek’, their drink was said to make a ‘marvellous’ ‘difference’. In just what way Milo was ‘marvellous’ and in what way(s) it was ‘different’ were not examined. But never mind, it had a catchy tune:

It’s marvellous what a difference Milo makes

Milo is best.

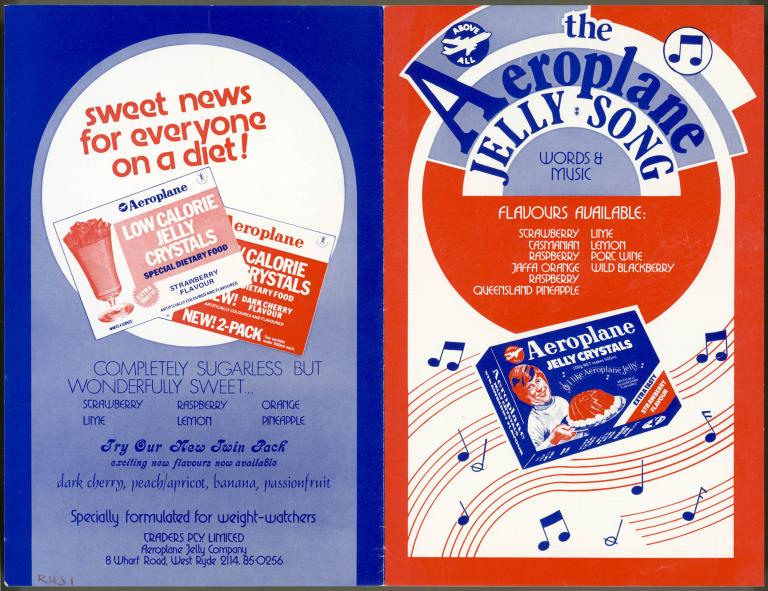

The most famous of all our pop anthems must be the ‘Aeroplane Jelly Song’. This ditty has been in our audio consciousness for well over half a century. Like Vegemite and Milo, it exhorts us to consume for our dietary well-being.

I like Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly for me.

I like it for breakfast, I like it for tea,

A little each day is a good recipe.

The quality’s high, as the name will imply;

It’s made from pure fruit, that’s one good reason why

I like Aeroplane Jelly,

Aeroplane Jelly for me.

But after the Milo, the Aeroplane Jelly and the Vegemite had been consumed there was a problem. What to do with the empty containers and dirty dishes? Sticky jars of black goo, globules of jelly clinging to bowls and Milo-encrusted cups had to be swiftly dumped or washed for fear of those other Australian icons, the bloody flies.

Vegemite solved the problem brilliantly by making the container a drinking glass. But this option was not available to the packagers of other foodstuffs, so the perennial problem of flies was exacerbated by garbage bins full of empty food containers. Fortunes were made by those smart enough to market fly-killing insecticides. None was more famous than the household name of Mortein.

To get us to buy their product and mercilessly cut down the fly menace, Mortein’s advertisers came up with the repellent cartoon character of Louie the Fly, whose song was a kind of antipodean ‘Hernando’s Hideaway’. Louie was a noisome beast of unfly-like size who lived on filth and rubbish, dripping black trails of disease across our TV screens, originally in black and white, more recently in full colour:

I’m Louie the fly, Louie the fly

Straight from rubbish tip to you

Spreading disease with the greatest of ease

Straight from rubbish tip to you.

I’m bad and mean and mighty unclean

Afraid of no-one –

‘Cept the man with the can of Mortein

Hate that word, Mortein, Mortein

Poor dead Louie, he couldn’t get away (Louie the fly)

A victim of Mortein;

Mortein.

The last section was Louie’s musical epitaph, sung in dirge-like tones. The viewers were left in no doubt that the great home insecticide would do its work well, protecting us from the consequences of our consuming and our cast-offs.

One of Mortein’s competitors was ‘Flick’, also a household name for many years. Just as Mortein protected the family from disease-carrying flies, so Flick undertook the defence of the home’s physical structure against the invasion of natural pests. Whiteants (or termites), wood borers and silverfish were the villains of the Flick jingle:

If there are whiteants in the floor,

Borers in the door,

Silverfish galore

Get a Flick man, that’s your answer

Remember, one Flick and their gone.

As well as our fascination with incineration and liquidation in the effort to protect family and home, we also worried about protecting ourselves from dirt. Cleanliness was not only next to Godliness, it cost so the advertisers assured us, next to nothing to attain. And it could be done in a jiffy.

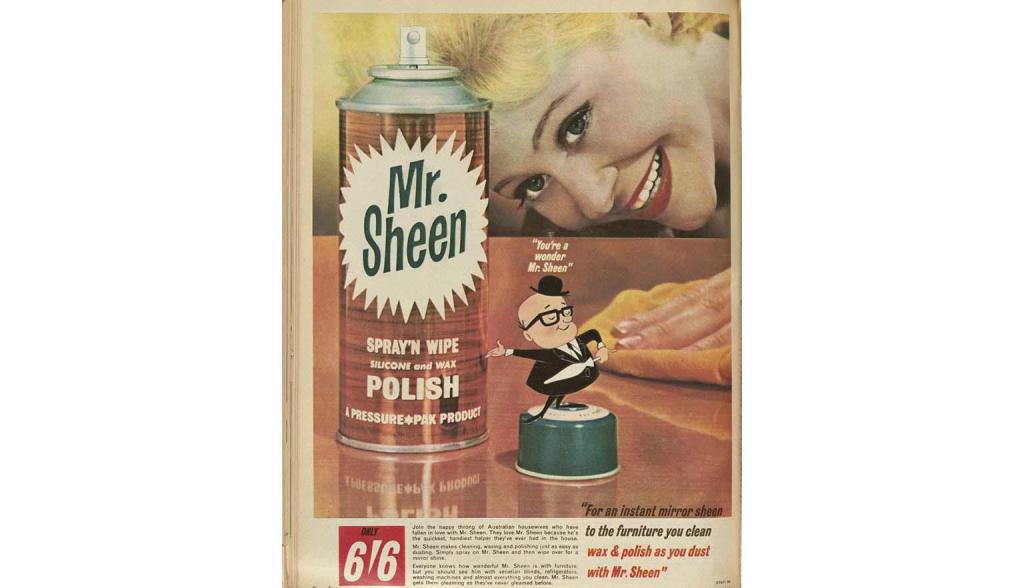

The strangely small, balding Mr Sheen appeared in the early years of telly and has returned from time to time, ever since. Mr Sheen cleaned your furniture in the twinkling of an eye – ‘it only takes one spray; to wax and polish it away’

Oh, Mr Sheen, Mr Sheen

You’re the quickest waxing trick we’ve ever seen

It only takes one spray; wipe it over right away.

Wax and polish as you dust with Mr Sheen…

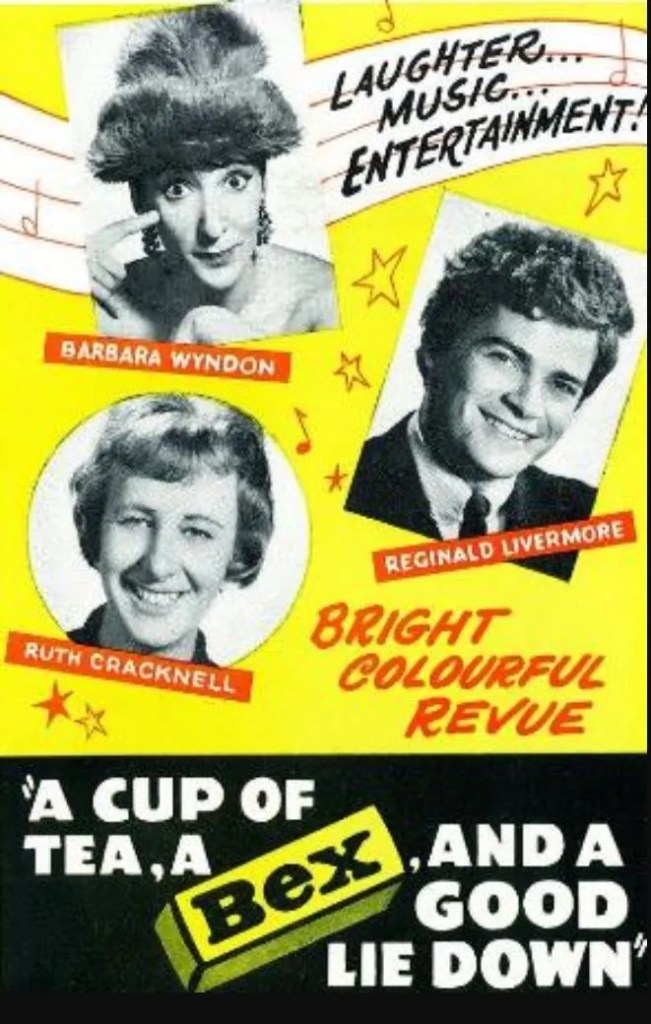

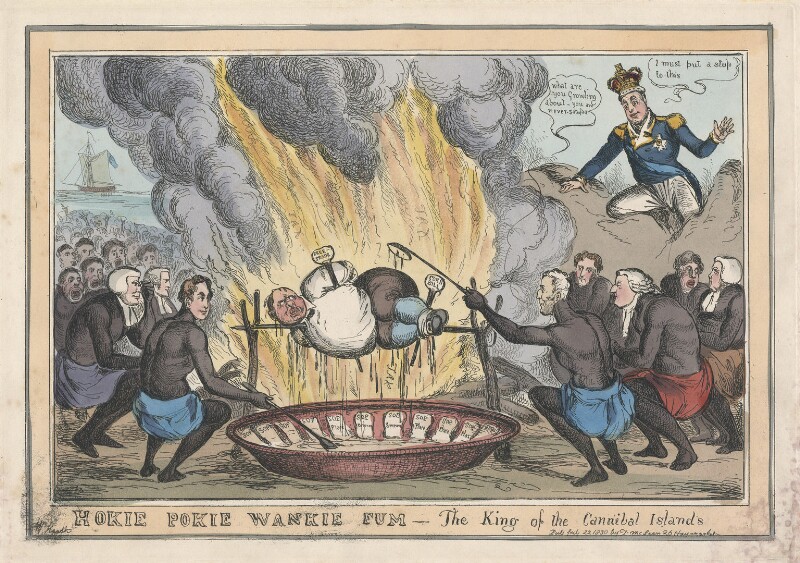

Excavating these musical icons of Australian commercial culture encourages some interesting speculations about our deeper concerns. Our pioneering ancestors feared the great unknown emptiness, its savagery and what they thought of as the strangeness of its animal and human inhabitants. In the age of consumption these paranoias have remained in our commercial culture. Protection from insects, dirt and poor health is a continual theme in these ditties.

As well as these cultural condoms we have sought to draw around us, Australians have been obsessed with foods that do us good and with avoiding the consequences of the filth resulting from our cast-offs. We have consumed concoctions as odd as the residue of beer-brewing, malted eggs and sugared gelatine. When we have finished eating and drinking, we have been concerned to clean up after ourselves, to make the grot disappear in the twinkling of an eye.

There are important differences between the visual and the musical icons of Australian commercial culture. The manly Chesty Bond, the stubborn Billy Tea swaggy and the bold colours of the Arnotts’ parrot suggest virility and confidence. But many of our most characteristic advertising ditties imply that we are really a nation of ‘Ovalteenies’, worried about our health and frightened of a bit of dirt and a few flies. Perhaps, in the slogan of another famous commercial of the past, Chesty Bond likes nothing better than ‘a cup of tea, a Bex and a good lie-down’?