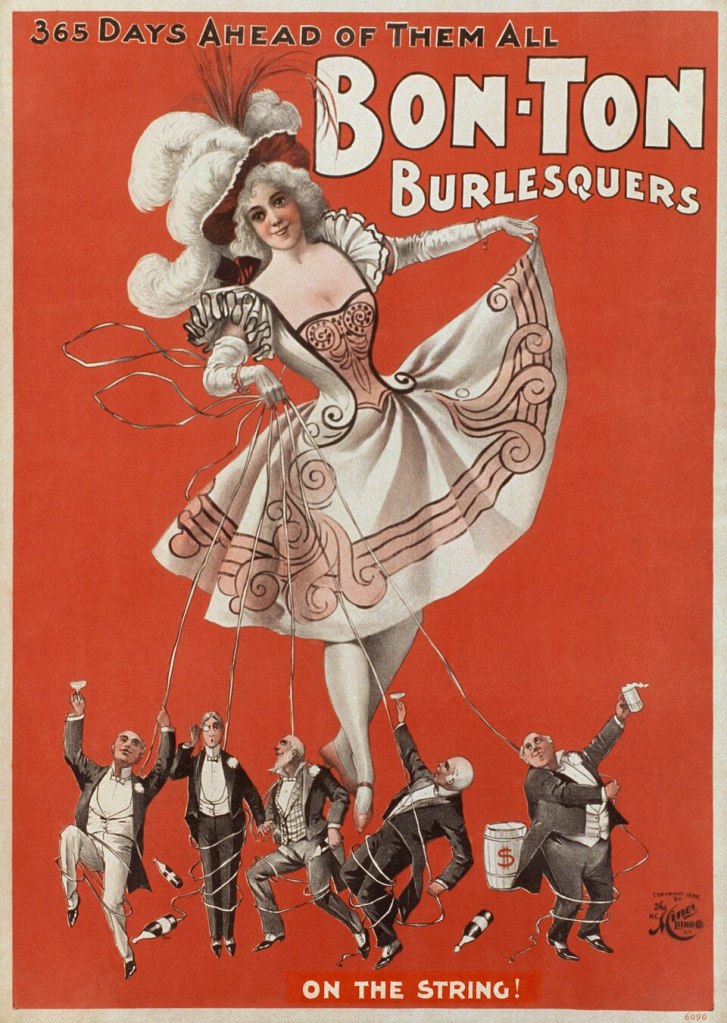

H.C. Miner Litho. Co. – Library of Congress[1]Bon Ton Burlesquers – 365 days ahead of them all.” Poster of U.S. burlesque show, 1898, showing a woman in outfit with low neckline and short skirts holding a number of upper-class men “On the string”. Color lithograph.

Burlesque comes from the Italian burla, for a joke or to mock – was characterised by the appearance of young women in relatively little clothing and what there was of that was designed to show their bodily form to best advantage. As well as this primary attraction for its mostly male audiences, Burlesque also had a strong element of social satire from its origins as lower class spoofs of high society diversions such as opera and ballet.

While Burlesque is usually associated with America it received its greatest boost in the 1860s when the famed showman P T Barnum imported a British Burlesque troupe led by Lydia Thompson. Lydia and her blonde ladies rapidly became superstars, although there was soon a strong moral backlash against this form of entertainment. As usual, this only increased the popularity of Burlesque and by the early twentieth century it operated through an extensive circuit of theatres, known as a wheel, with large troupes travelling the same show for up to forty weeks of the year. By then, the typical Burlesque show included many of the same style of acts found in Vaudeville, although the scantily clad ladies remained the primary attraction.

In burly-q speech the main player in a comic act was known as the top banana, a phrase that has entered the broader slang repertoire. Those supporting him or, less frequently her, were second banana, third banana and so on. These terms are said to derive from the comic’s last resort of slipping on an imaginary banana skin in order to get a laugh. In this form of slapstick (a term derived from pantomime rather than burlesque, though this very basic form of humour was common to both forms), the lower a performer ranked in the bunch the more likely he or she was to receive the pies in the face and the host of other undignified bits, or skits, that made up most comedy acts. Other terms related to the business of being funny were skull – to pull a funny face and the talking woman – one who delivers lines for the comic to joke about, equivalent to the straight man of a stage comedy act.

An oft-performed bit from the later Burlesque poked fun at business names. It doesn’t take much to see and hear a couple of the Marx Brothers banging this one out:

Man at Desk: (picks up phone) Hello, Cohen, Cohen, Cohen and Cohen.

Caller: Let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man at Desk: He’s dead these six years. We keep his name on the door out of respect.

Caller: Then let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man: He’s on vacation.

Caller: (Exasperated) Well then, let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man: He’s out to lunch.

Caller: (Yells) Then let me speak to Mr. Cohen!

Man: Speaking.

The occupational jargon of burly-q included colourful phrases like the asbestos is down – a reference to the fireproof stage curtain being down, making the audience unable to hear the jokes – which purportedly explained why they were not laughing. A mountaineer was a comic from the Catskill Mountains resort circuit and the Boston version referred to a sanitised rendition of an act with the blue elements removed or toned down. The term cover, meaning to take over another performer’s role, as in ‘Will you cover for Mac?’, has passed into the wider vernacular of the English-speaking world, its Burlesque origins known by few.

Despite the similarities between Burlesque and Vaudeville, there was a barrier between the forms, with Vaudevillians considering themselves superior to Burlesque. But the continual operating mode of the Burlesque circuit meant that it provided fairly reliable work and many Vaudeville acts also worked the Burlesque circuits under different names. As a result, there is a considerable overlap between Vaudeville and Burlesque lingoes. The olio was used in both forms to describe a mixture of short acts performed rapidly at the front of the stage with the main curtain, often an oilcloth, a technique probably borrowed from the earlier blackface minstrel shows. Other common terms included yock and milking an audience, the latter of which became a standard showbiz term and has moved beyond that into everyday slang.

Like Vaudeville, burly-q declined with the rise of the cinema. By the 1920s it had become largely a bump and grind strip show, with the comic acts little more than a hangover of the past. The striptease developed its own language as well. Strippers used pasties to cover their nipples. A G-string was a gadget, while a trailer was the provocative walk leading up to the strip itself. The breasts of a stripper were blisters to be quivered and her buttocks were cheeks to be shimmied for the titillation of the audiences, known in the business as jerks.